Yesterday, GE announced that they had put in bids to acquire both Arcam and SLM for a combined total of $1.4B. This move poses some interesting questions about the next few years in industrial AM, and will no doubt have a big impact on both the companies involved and their customers and competitors. I don't have any privileged insight into any of these companies' decision making process, but I have a longstanding interest in the industry and what they're working on. Here are a few observations & questions that occurred to me about the deals and their impact.

Background

In 2012, GE Aviation made three large acquisitions in industrial AM. The first was the combined purchase of Morris Technologies and Rapid Quality Manufacturing, two sister companies based in Cincinnati who had already been a big supplier to GE Aviation (terms of the deal were not disclosed). Later that year, they bought Avio Aero, and Italian parts supplier, for $4.3B. These two purchases showed an interesting balance in technologies. While Morris and Avio had very similar business models (both were job shops that produced parts for GE Aviation and other business units; Avio also produces parts by traditional manufacturing methods), they focused on different additive technologies: Morris on laser, and Avio on EBM.

I've written about the difference between laser and EBM in the past, but a few points here:

- The fuel nozzle that GE is so famous for printing is made by laser in Auburn, Alabama on EOS machines. I believe that their (lesser known) T25 temperature sensor is made on the same machines.

- The laser (Note: I'm using "laser" here to refer to processes that are variously called DMLM, SLM, DMLS, lasercusing, and the generic "laser metal powder bed fusion." Note also that SLM can be used to refer both to the printing process AND to the machine manufacturer that GE just acquired.) machine market has a number of providers: Aside from EOS and SLM (the two machine manufacturers that GE is most known for using) there's Renishaw, Concept Laser, Additive Industries, 3D Systems, and a variety of Chinese entrants.

- While GE Aviation has tended towards EOS machines (see the video above), GE Power & Water uses machines made by SLM in their Greenville, SC plant (Note: Here I'm drawing from an AMUG 2015 and other industry sources; sorry for the lack of a hyperlink reference).

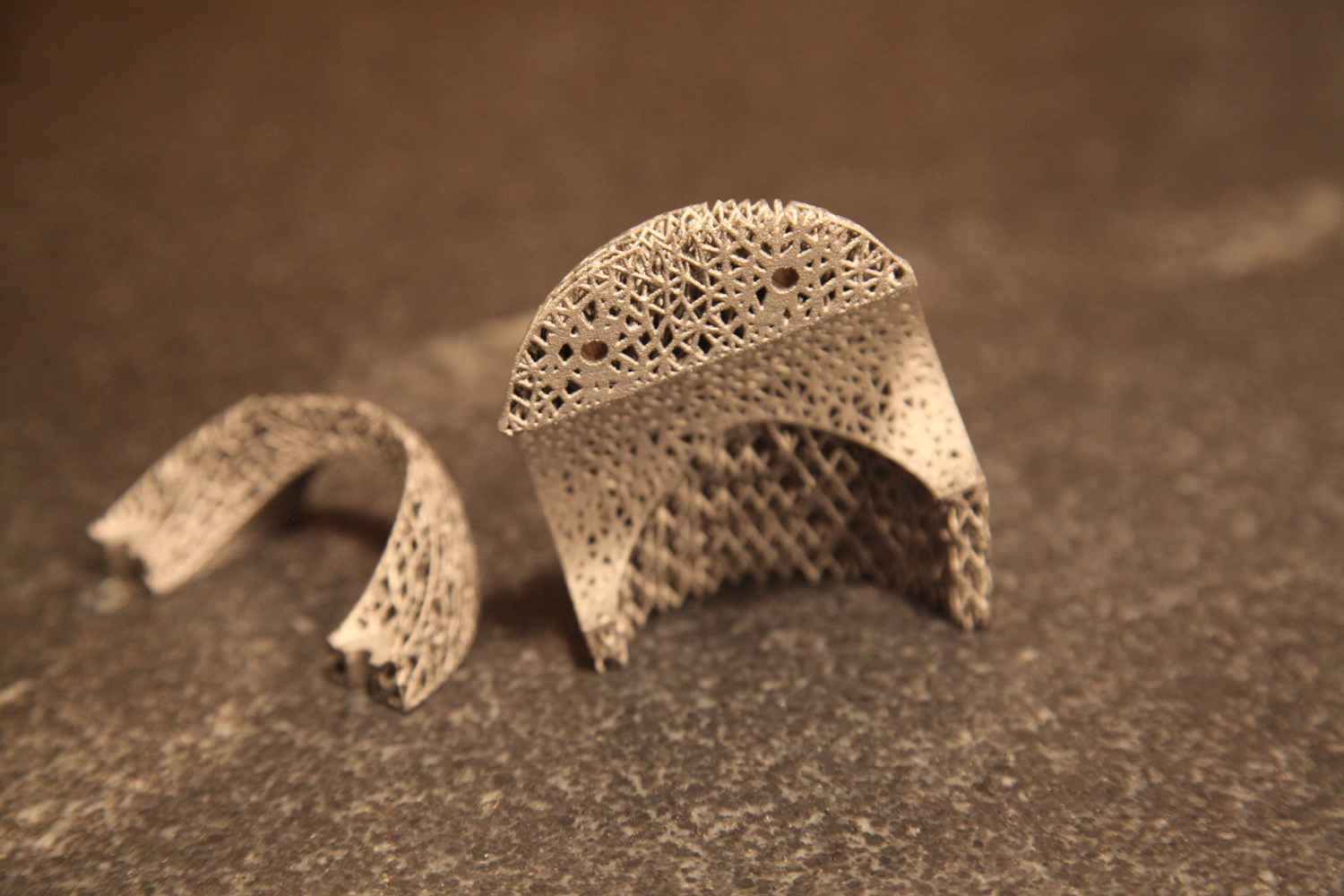

- Arcam sits apart from these: it's currently the only company making machines for EBM (electron beam melting, or "electron beam metal powder bed fusion" if you're picky).

- Avio Aero has done some really interesting things with EBM since the GE acquisition. Perhaps most notably, last year they printed low pressure turbine blades out of titanium aluminide, an intermetallic alloy. TiAl has excellent mechanical properties at high temperatures (an important feature of any part that's in the hot stage of a jet engine), and is traditionally cast by companies like Precision Castparts Corp (PCC). Printing in TiAl brings advantages but is extremely difficult due to the material's tendency to fracture. Printing TiAl could be a big deal as GE ramps up production of TiAl blades for the GEnx engine, and it was very interesting to note that after the successful prints, Avio bought an additional ten Arcam systems - the largest purchase that Arcam had ever accepted.

So: GE already had a strong portfolio in additive. What are the implications of the Arcam and SLM acquisitions, and how will this impact the industry?

A full stack, in-house

The most interesting part of the acquisition to me is the fact that GE will now be able to in-house the entire industrial AM supply chain (minus software; more on that below). Previously, they were focused primarily on basic research and applications development (Morris, Avio, CATA, and the Niskayuna Global Research Center) and serial part production (Auburn, Greenville, and Avio). Now, they'll own not one but two machine manufacturers - allowing them to push upstream and make a more direct impact on the development of the additive industry.

But perhaps more importantly, GE gains both powder production (through AP&C, the Canadian powder supplier that Arcam acquired for CAD 35MM in 2014) and final parts manufacturing (through DiSanto, the medical implants manufacturer that Arcam acquired for $18.5M later the same year). When Morris was acquired, they shut down their sales organization and focused on printing parts for internal GE customers. DiSanto is a very different business, though, and I wonder whether it might make sense as part of GE's healthcare unit - with its traditional focus on medical imaging and healthcare IT.

AP&C is a bit of a different beast. They manufacture the raw materials for not only powder bed fusion but also MIM, HIP, and other powder metallurgy applications. Their website advertises commercially pure titanium and ti64, but Arcam also markets cobalt-chrome - which both the fuel nozzle and the T25 sensor housing are made of. I'll be very curious to see whether AP&C continues selling powders to the public, or if they focus on internal use.

Improving - and selling - manufacturing machines

Separate and apart from the implications to GE's internal operations, I'm particularly interested in the way that GE's involvement at these new levels of the tech stack will affect how the industry matures. Try though they may, it's difficult for a company whose bottom line depends on selling machines (as opposed to, say, selling machines AND printing parts, or selling machines AND developing manufacturing software) to truly impact the end-to-end engineering process much. And while GE has been at the forefront of additive research (and, no doubt, collaborates very closely with both their hardware and software providers), I'm hopeful that having them at the helm will push both EBM and laser powder bed fusion forward in a cohesive way.

Some might suggest that keeping expertise in house would be the strategic choice here, but I disagree. Powder bed fusion today suffers from both a lack of talent (easiest to change by expanding the number of use cases for the process, many of which GE ultimately is not going to compete on) and a lack of process predictability and reliability. GE has more knowledge about improving AM part yield than just about anyone else in the world, but that doesn't mean that there aren't other approaches that they're not trying. Inasmuch as sharing whatever process improvements they come up with will encourage others to try their own approaches, I hope that GE does just that. And they have in the past: through their involvement with standards and industry organizations like America Makes, 3MF, and ASTM F42; through their participation in sessions at AMUG and RAPID, and through their open innovation work (some of which I worked on while at Undercurrent) with GrabCAD and NineSigma.

My hope would be that GE continues to market and improve both SLM and Arcam machines. The latter is particularly dear to me, as EBM equipment isn't currently made by anyone else (and because I've had many parts printed on Arcam machines). SLM is a bit different, as the market for laser powder bed fusion is already so rich. But by that same rationale, the potential impact that any updates to SLM's machines would have could be huge, as they would force other players to respond in kind.

Software

I take GE at their word: They want to be a contemporary engineering company, and they believe that contemporary engineering companies need formidable software capabilities. And if they're going to truly make their mark with a software solution, it would be wise to do so in a realm where they know the problems well.

Even before these acquisitions, GE knew the pain points in additive as well as anyone else. Adding a few machine manufacturers, plus a raw materials supplier and a finished parts manufacturer, will only help that along. So my question is this: Why wouldn't GE make a play in additive manufacturing software? This is, after all, the whole subtext behind the Brilliant Factories initiative: GE knows how hard it is to make things, and they can help you make them better.

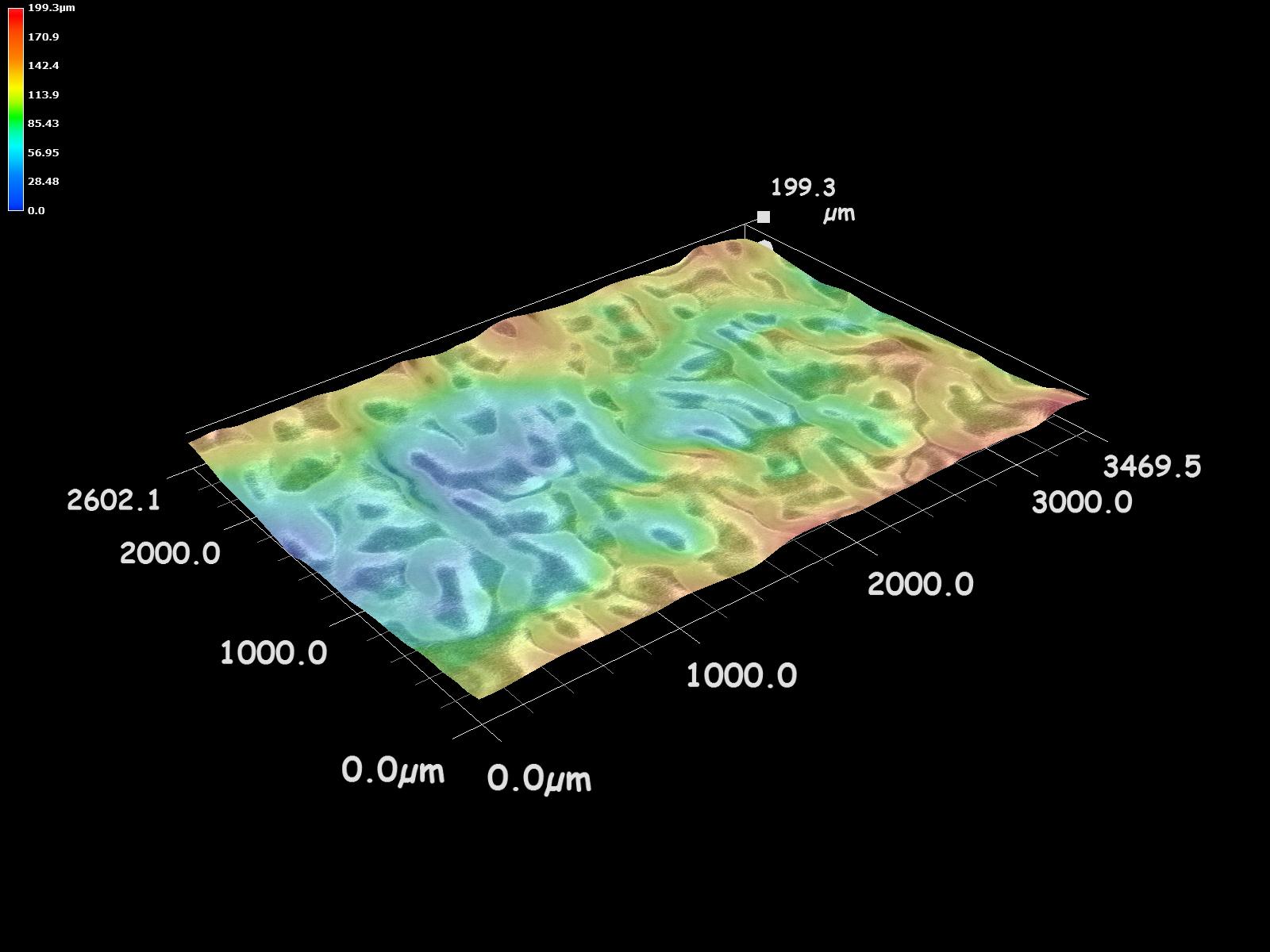

As you'll know from my previous writing, I'm excited for advances in build processing (see netfabb and Magics), build simulation (see 3DSim and Pan Computing, and research by Wayne King at LLNL), and in-process monitoring & control (see Sigma Labs, plus the product spec sheets for a *lot* of the current class of laser printers). Each of these is extremely hard in itself, and recreating the entire stack would be extraordinarily complex; I don't expect any one company to solve (or even attempt) them all. But whether they build their own solutions or work with external providers to build them, GE will be a huge stakeholder in the next generation of additive manufacturing software. And if they're serious about being a formidable software company, then why wouldn't they take a shot at building it themselves?

Regardless of how these acquisitions shake out, the next year should be interesting. I'm looking forward to it :)