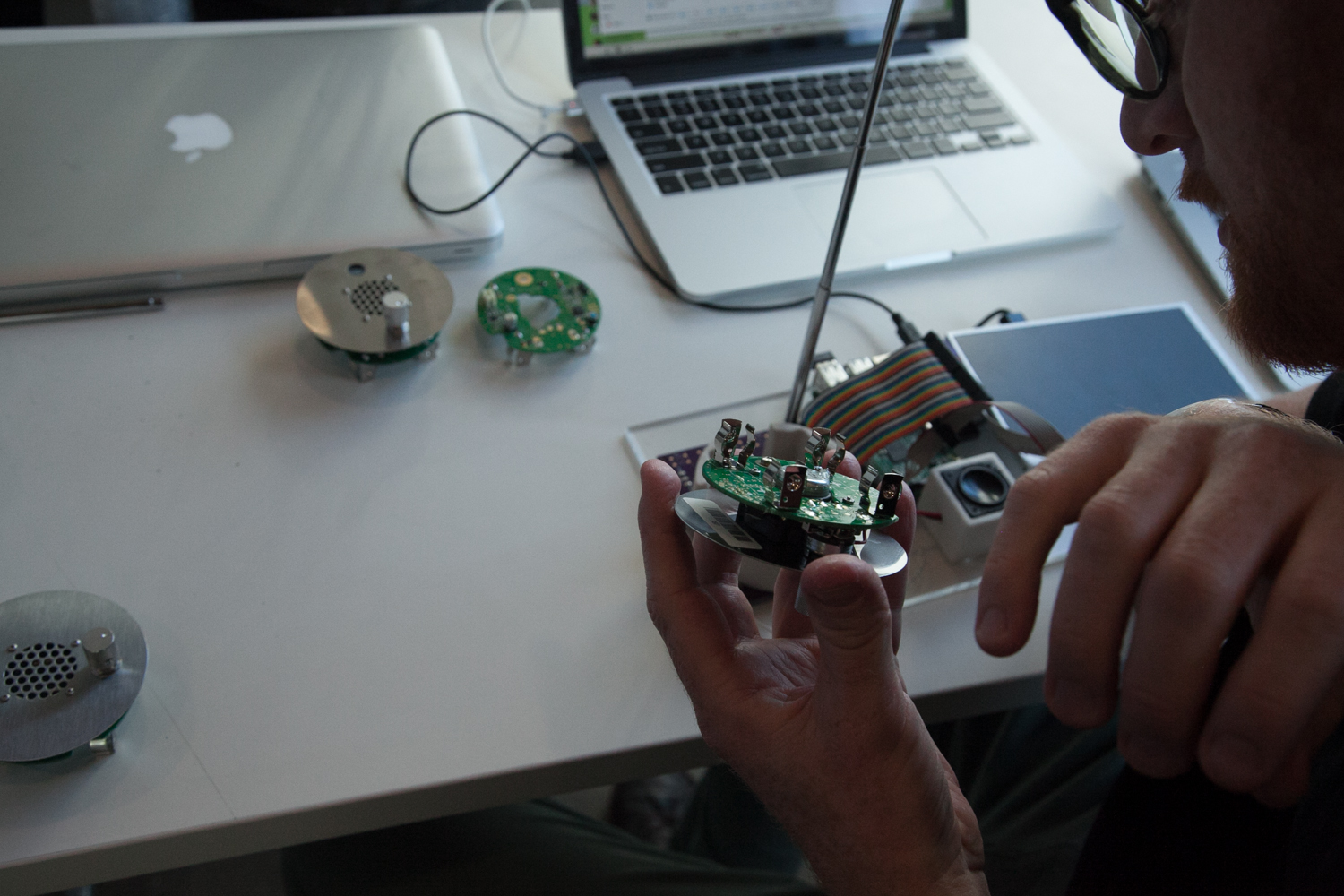

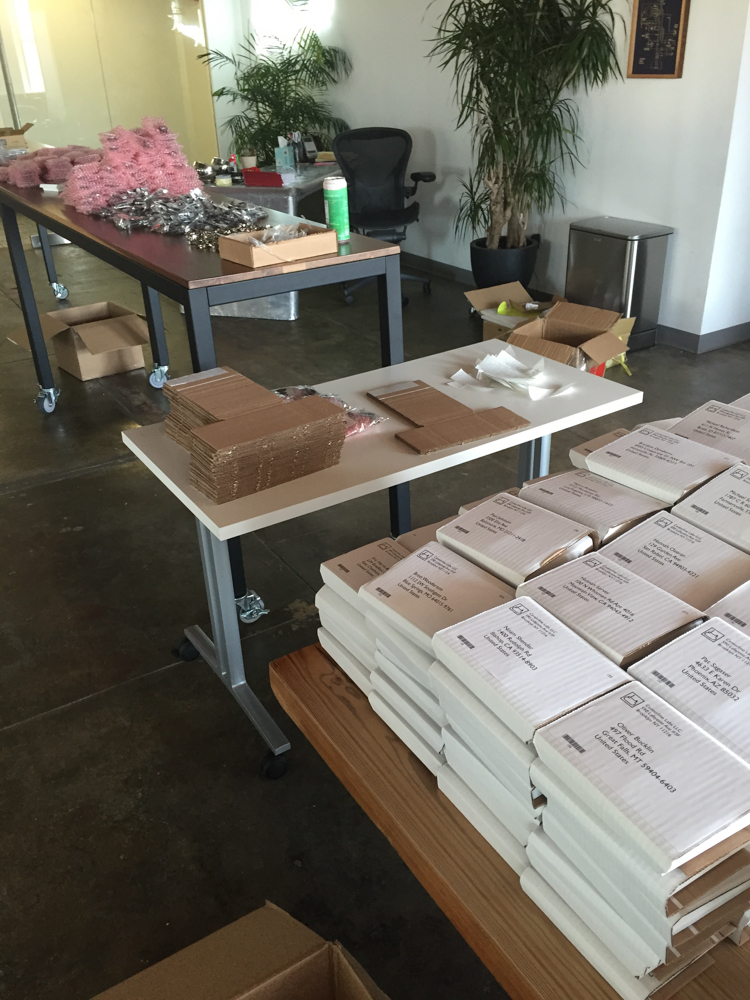

Today I had the pleasure of visiting Tesla's Fremont factory, where every single Model S is built. While they don't allow photos on the tour, I did take this pano to prove that I'm not fabricating the whole thing (but seriously though, a Google Image search does a decent job at showing you what it looks like inside):

Anyway, a couple of thoughts came to me on the tour, and I wanted to share them:

- First of all, the whole place is an information overload. It's noisy (not at all unbearable, but still), and the tour is a whirlwind - the whole thing took just over an hour. Moreover, the entire building is filled with visual clutter. It's all stunningly beautiful, but there's just so much going on, and it's nearly impossible to see, analyze, and understand what you're looking at, what's being done to it, and which direction it's headed in the assembly line, before the train of golf carts that you're being dragged around in speeds off to the next thing. This is not meant to be a criticism of either the tour or the factory itself, and I'm sure an automotive engineer would have an easier time soaking things in than I did, but for the majority of the tour I struggled.

- Lot of emphasis on sheet metal. Elon Musk loves his aluminum, and the tour itself is expressly directed towards the hydraulic presses that Tesla uses to turn rolls of aluminum sheet (from what the tour guide said, I suspect it's 16ga) into a car.

- The tour also emphasized the economy that Musk/Tesla employs in building up their capabilities. The core story here is that American manufacturers (GM is called out by name, mostly due to the fact that they're the former owner of the NUMMI site, which you should learn about) don't want/need big equipment or industrial space in the US anymore, and so Tesla has been able to buy this stuff for a song. So the purchase of their largest hydraulic press (the biggest in North America); the decision to use a Lotus platform for the Roadster; Tesla's use of the factory itself; - all of these are described (not inaccurately) as shrewd financial decisions.

- Interestingly, the only other brand names that get shout-outs on the tour are all Robotics companies: Kuka, ABB, and Fanuc. That fact - combined with the legendary stuff (all apparently real) about many of these robots having X-Men names - and the fact that the tour also highlights the human craft that goes into a range of sexy (and not-so-sexy) features of their cars - gave me the distinct feeling that Tesla consciously makes their industrial automation efforts seem as anthropomorphic as possible.

- This has been reported before, and it's worth noting again: Tesla's current production is about 1,000 vehicles per week. In the NUMMI days, this same facility turned out about 6x that.

- One thing that I was somewhat surprised by: Towards the end of our tour, the guide paused to explicitly note Tesla's purpose: To help expedite the move from a mine-and-burn hydrocarbon economy towards a solar electric economy. To be sure, I personally find this statement to be the most compelling thing about Tesla/Musk, if not the most compelling thing about any public company in the world (if you haven't read Musk's Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan, I'd really implore you to do so). But to hear it called out on a factory tour, to an audience which was made up almost exclusively of Tesla owners (besides a Tesla employee who had brought their family, I believe I was the only person *not* picking up a Model S right after the tour), seemed downright canny. Which leads me to my real observation:

Tesla is not, first and foremost, a manufacturing company; to wax on about the factory tour would miss the point. Their focus is simple: Musk has a singular vision for how the global energy lifecycle should work, and Tesla is doing whatever's necessary to bring it to fruition. Tesla is an energy company, and they're a "we're doing this because we believe in it and goddammit nobody else will" company. Which is really admirable, and it pleased me to see them use their factory - which, in spite of its relatively low throughput, is certainly a spectacle to behold - as a way to convert people to their mindset.