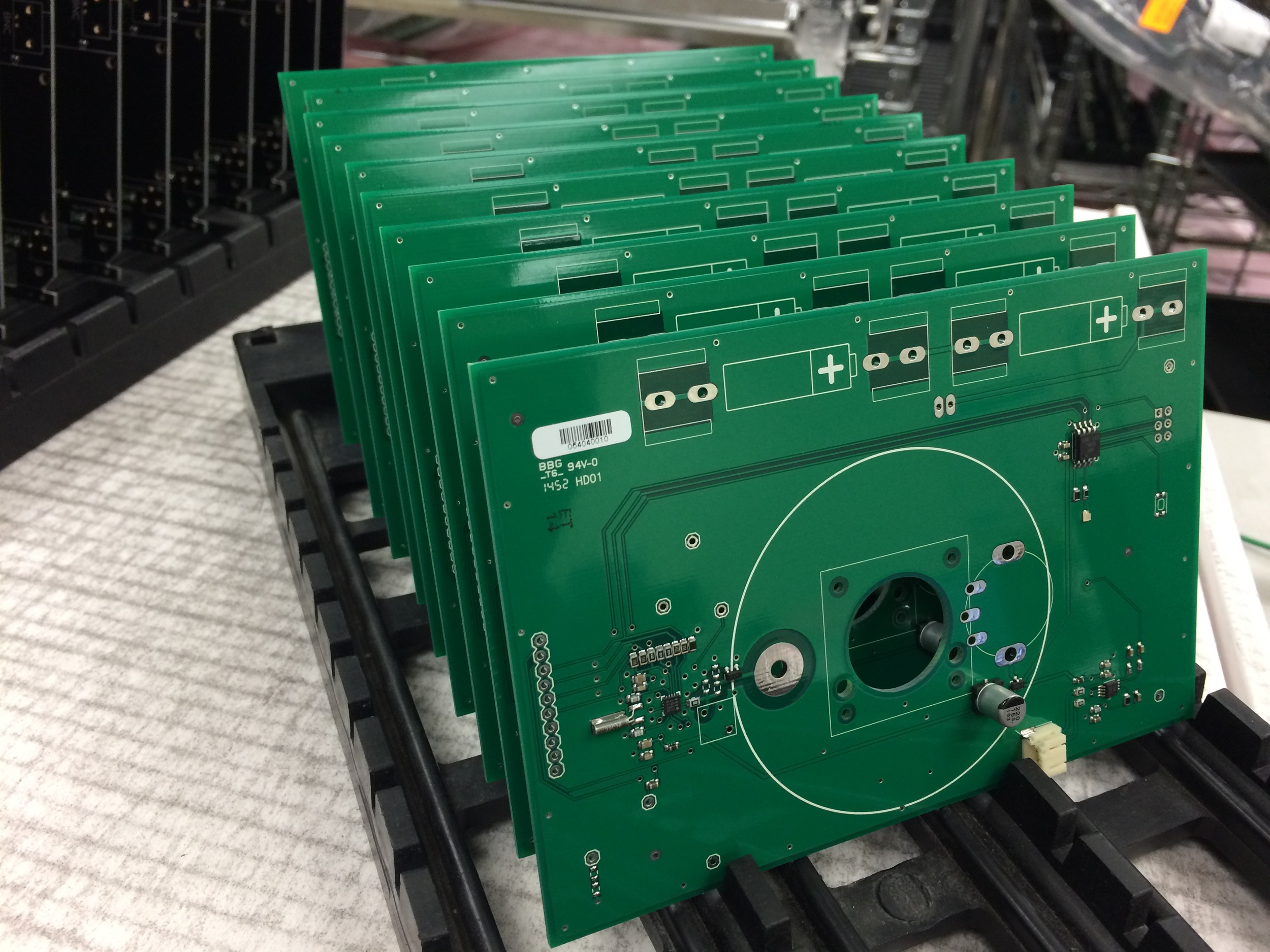

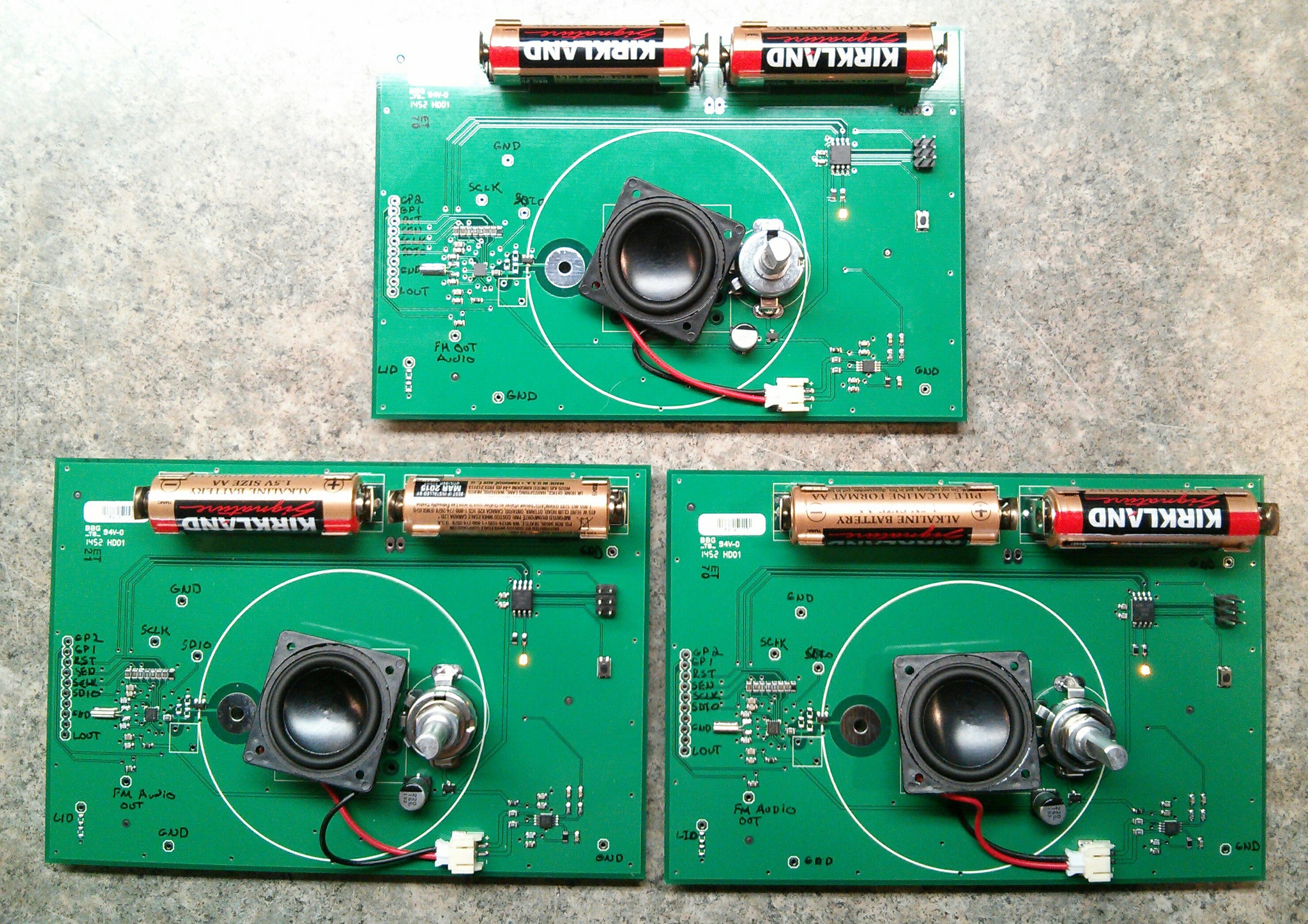

Early this week, I handed over 250+ of The Public Radio's "Maker Kit" Kickstarter rewards to a friendly USPS employee. It was a big step forward, but the fact is that the real production hurdles are all ahead of us. Although we have most of our tools built and tested, a few steps still need to be ironed out, and we have a bunch of work to do this weekend to secure the mechanical assembly workflow.

So this evening I spent a while setting up an assembly line at the Undercurrent office. We have a handful of volunteers coming by tomorrow morning, and it was great taking a little time beforehand to get things arranged how I *think* they'll be most efficient. It was also just good to think about what the possible bottlenecks could be, which to be honest I haven't had much time to do.

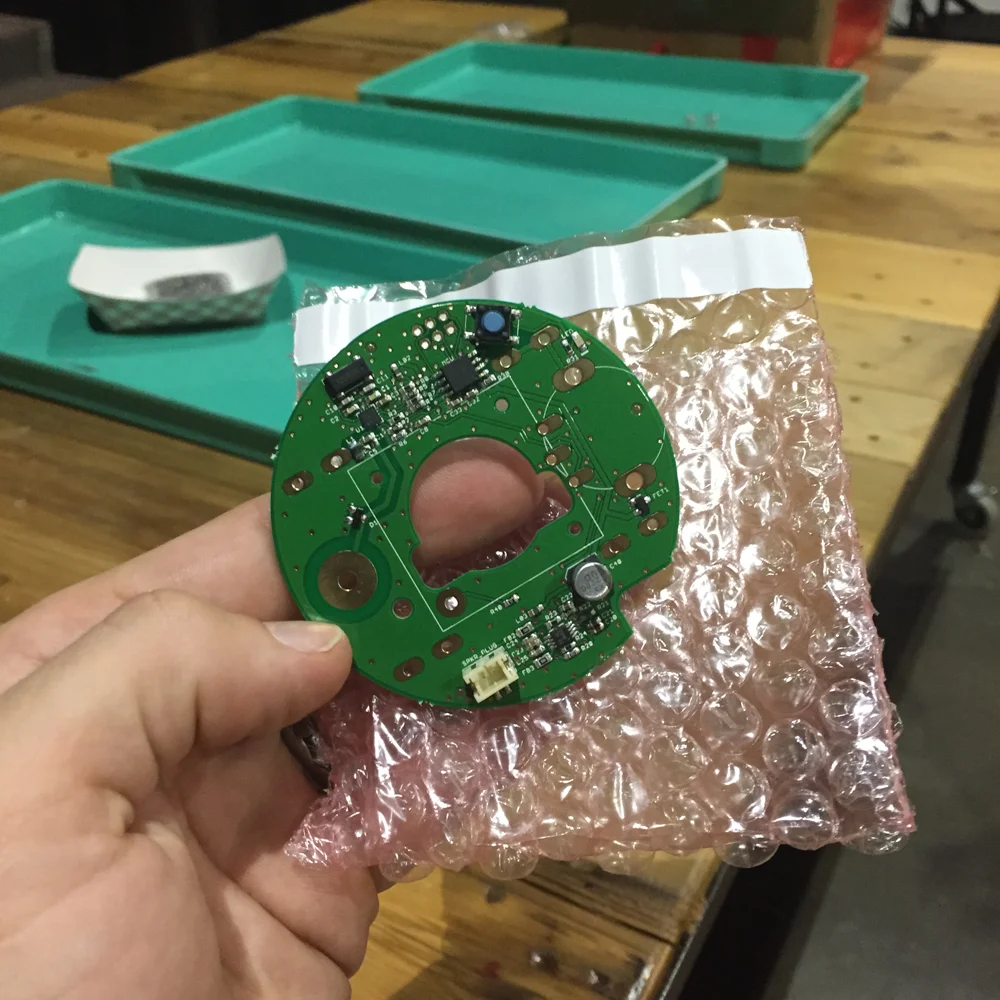

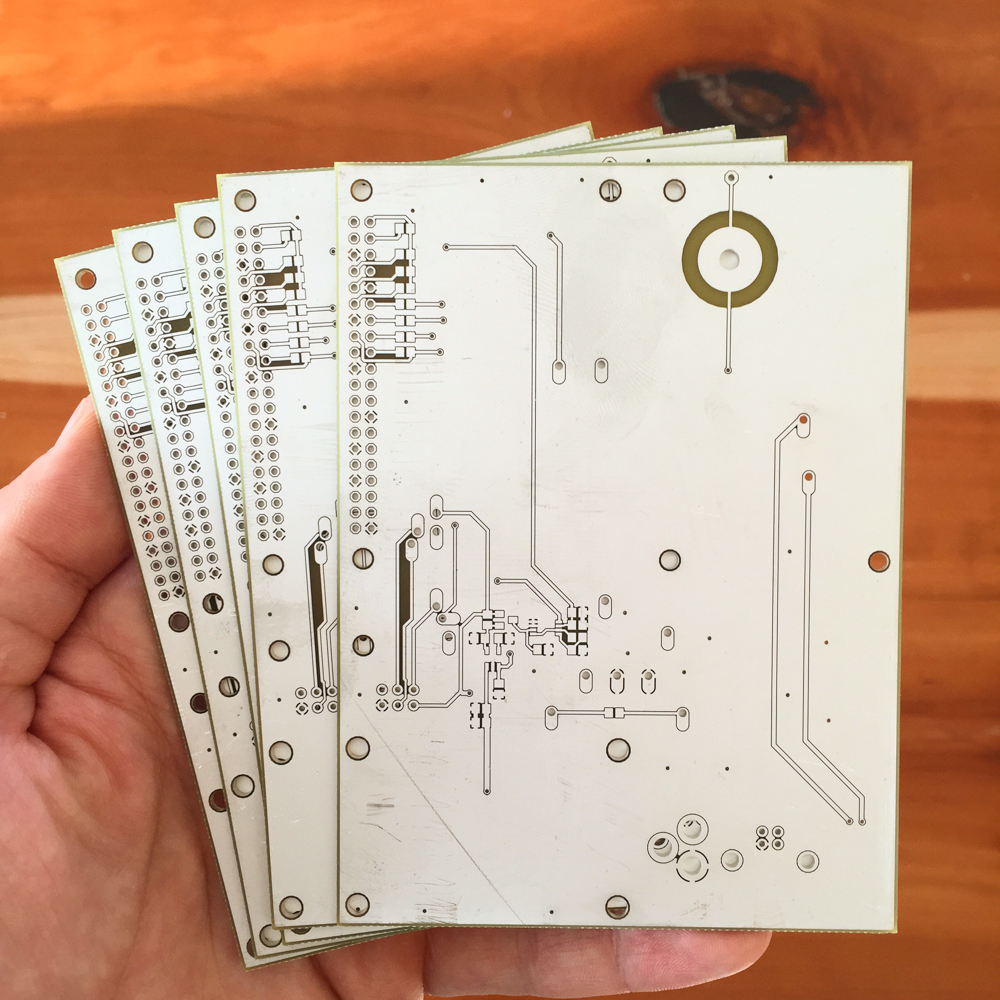

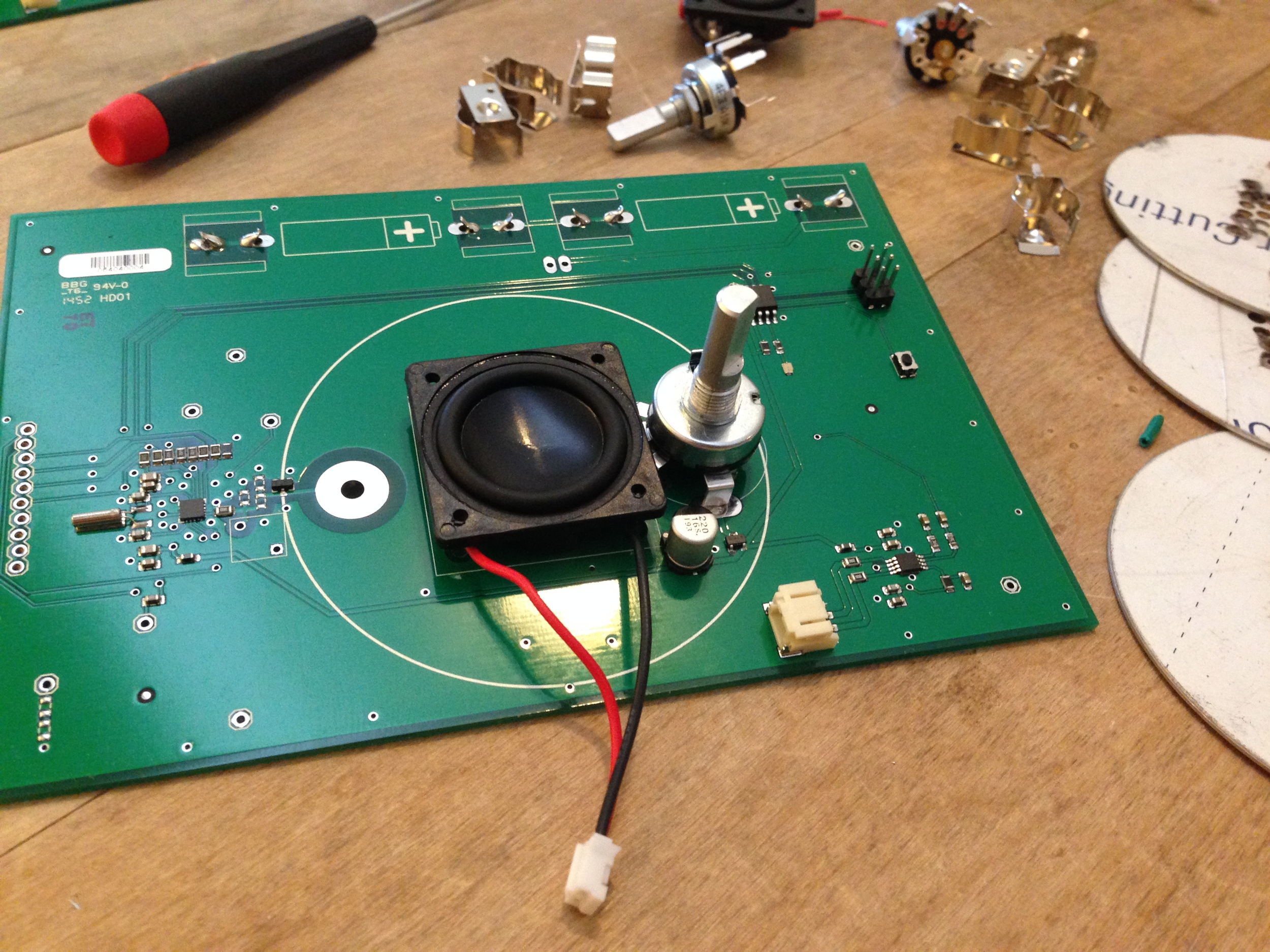

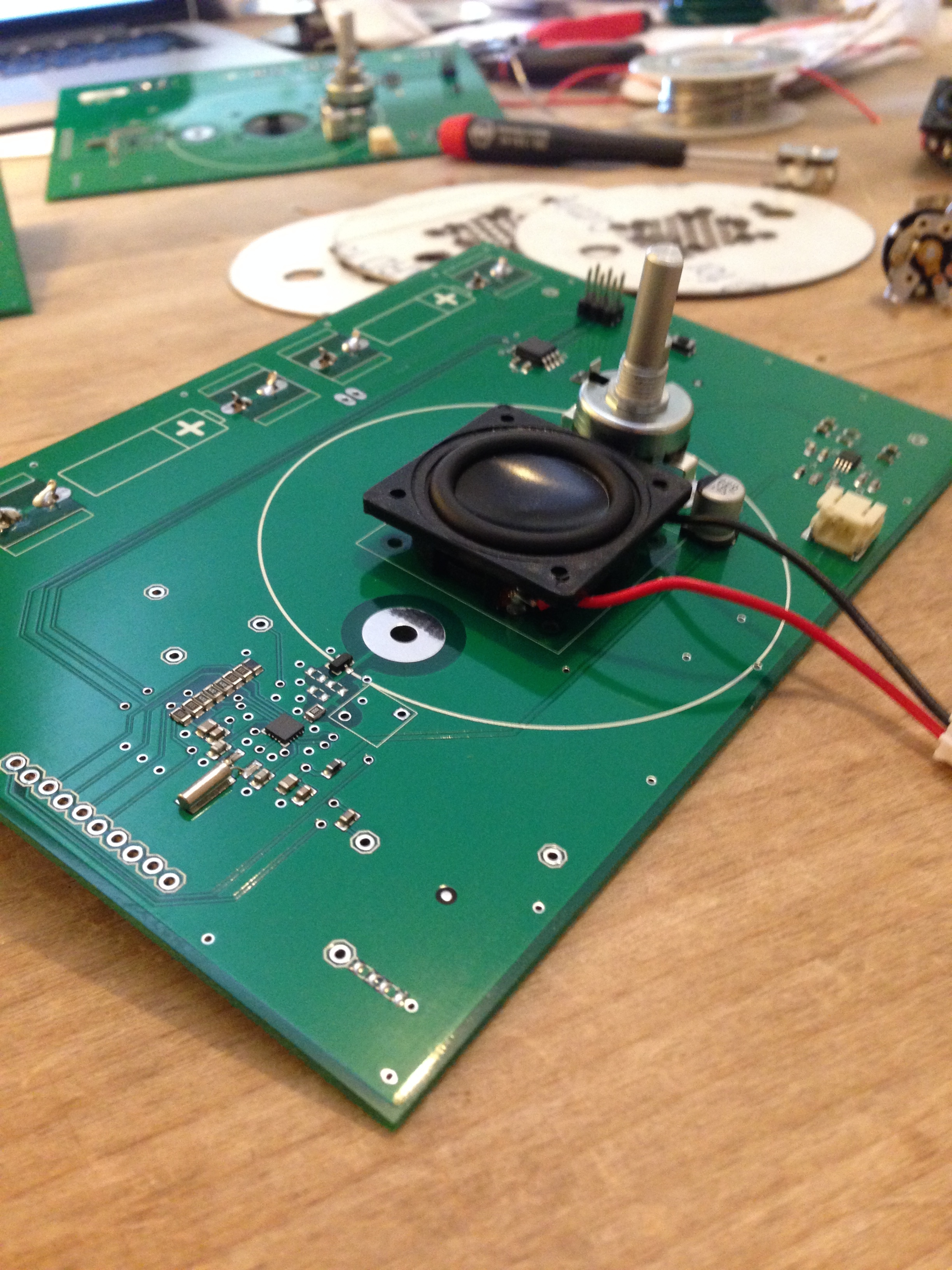

I documented the hand-assembly process of The Public Radio here, but what I didn't show is how it might work in a small scale production line. I also glossed over a few tricky steps, and the weird anomalies that I'm sure will come up. For my own benefit as much as anyone's, here are the questions that are foremost on my mind right now:

- Can we use an offset screwdriver (like this Klein one) for the antenna screw, or do we need to use traditional electronics type screwdrivers (like this Wiha one), which will probably be slower?

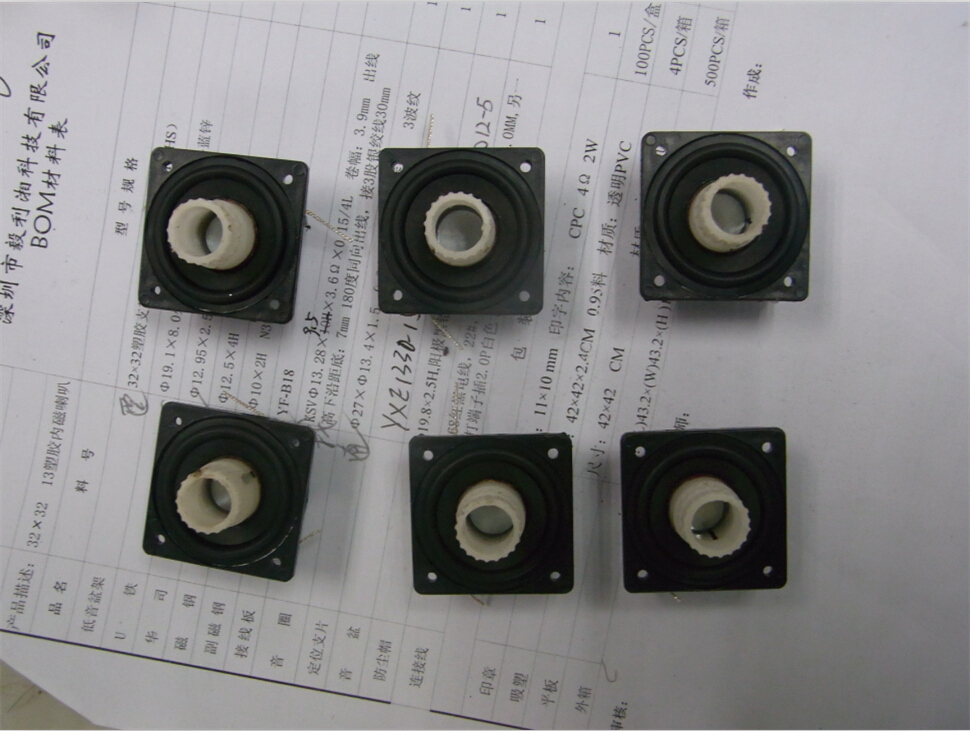

- Is the hot glue on the speaker going to be a total pain in the ass to apply? Do we need a different glue formula, or application method?

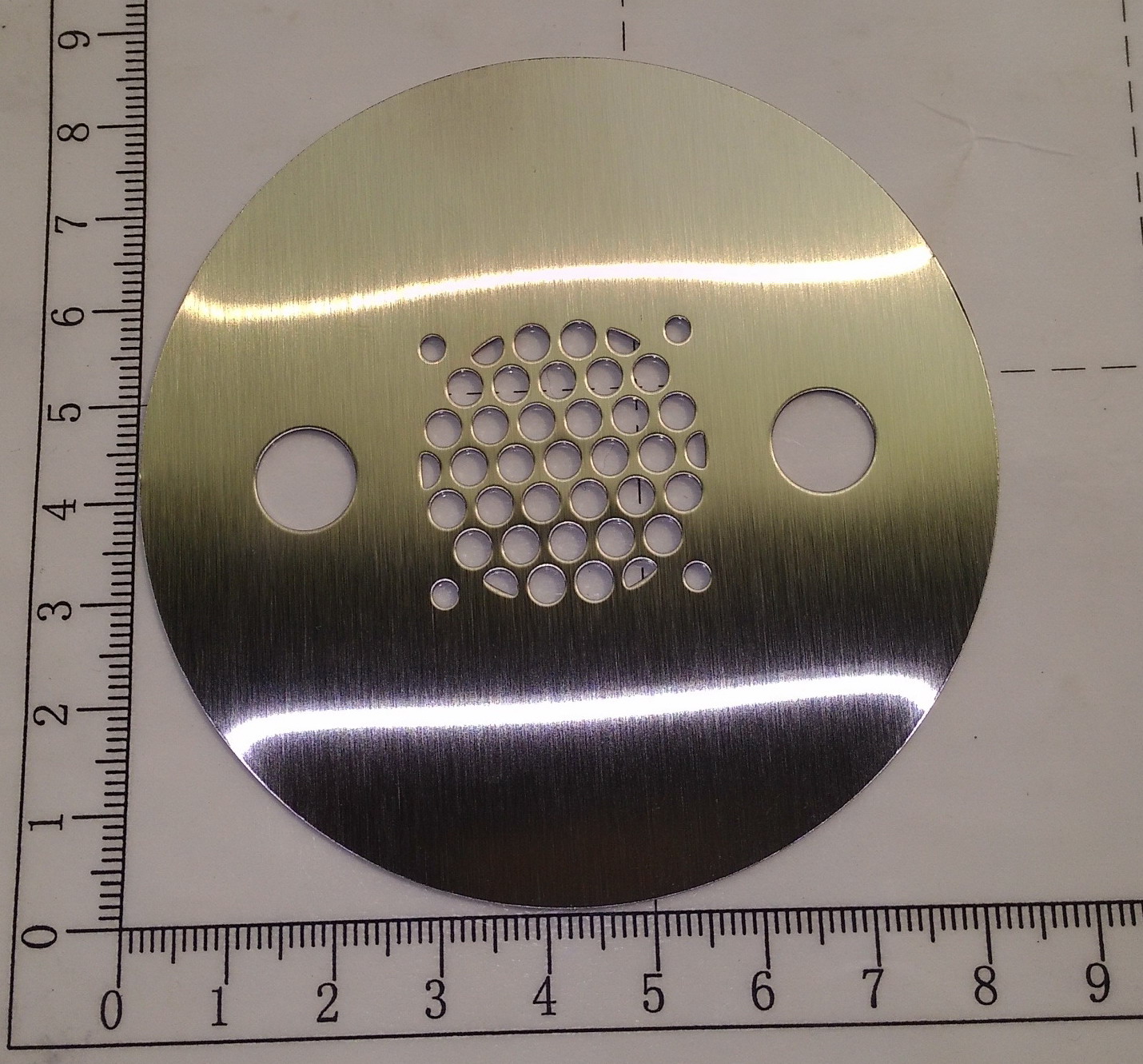

- Will the speaker wires get in the way of the speaker screws? This was a bit of an issue with late prototypes, and I'm anticipating a bit of manual manipulation (read: fucking around with the wires with your fingers before the speaker is glued down) in order for everything to work out. Is that going to be problematic?

- Will the speaker wire length be appropriate? We made the wires a bit long to start, figuring that it's better for them to be long than to be too short. How will the extra slack affect assembly?

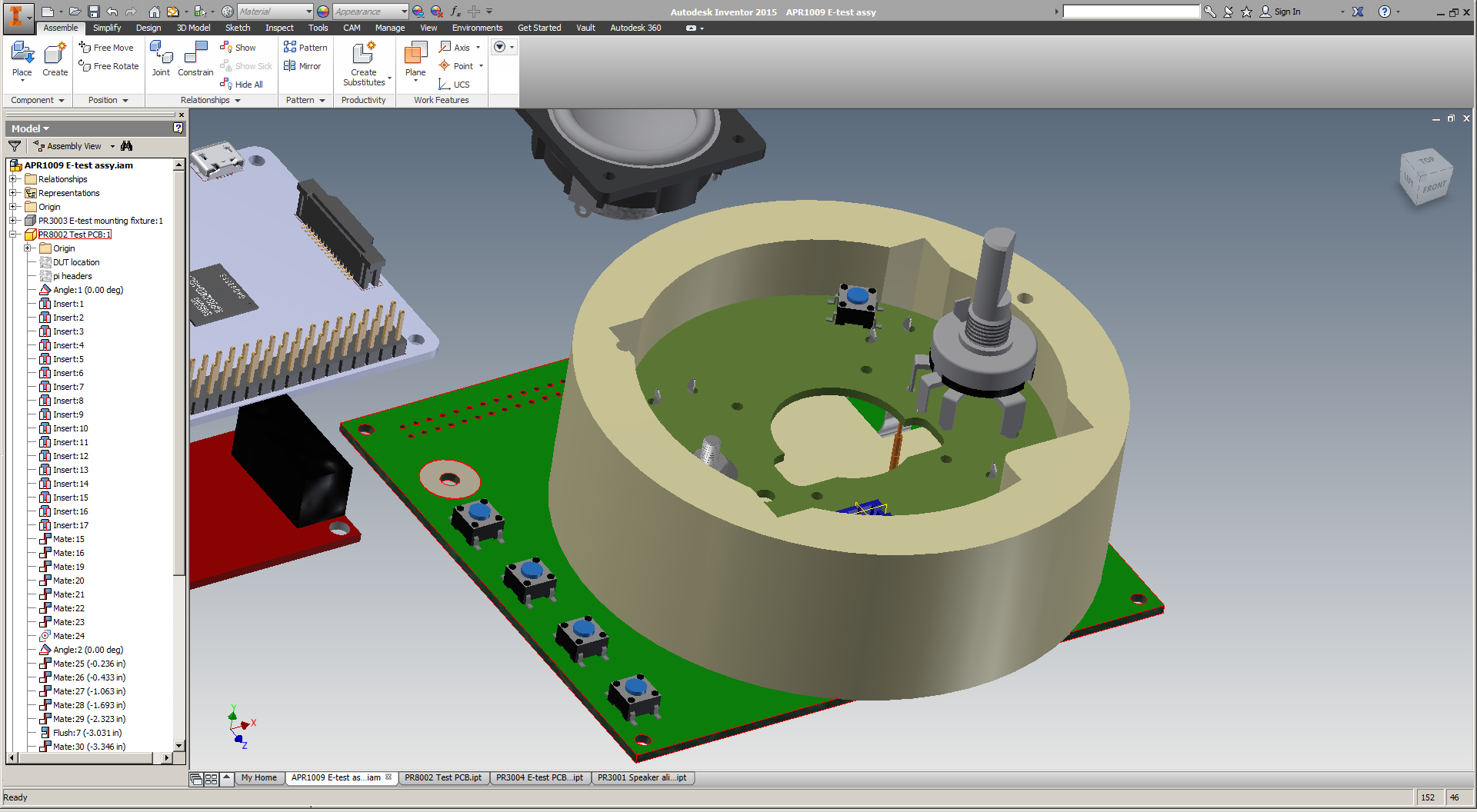

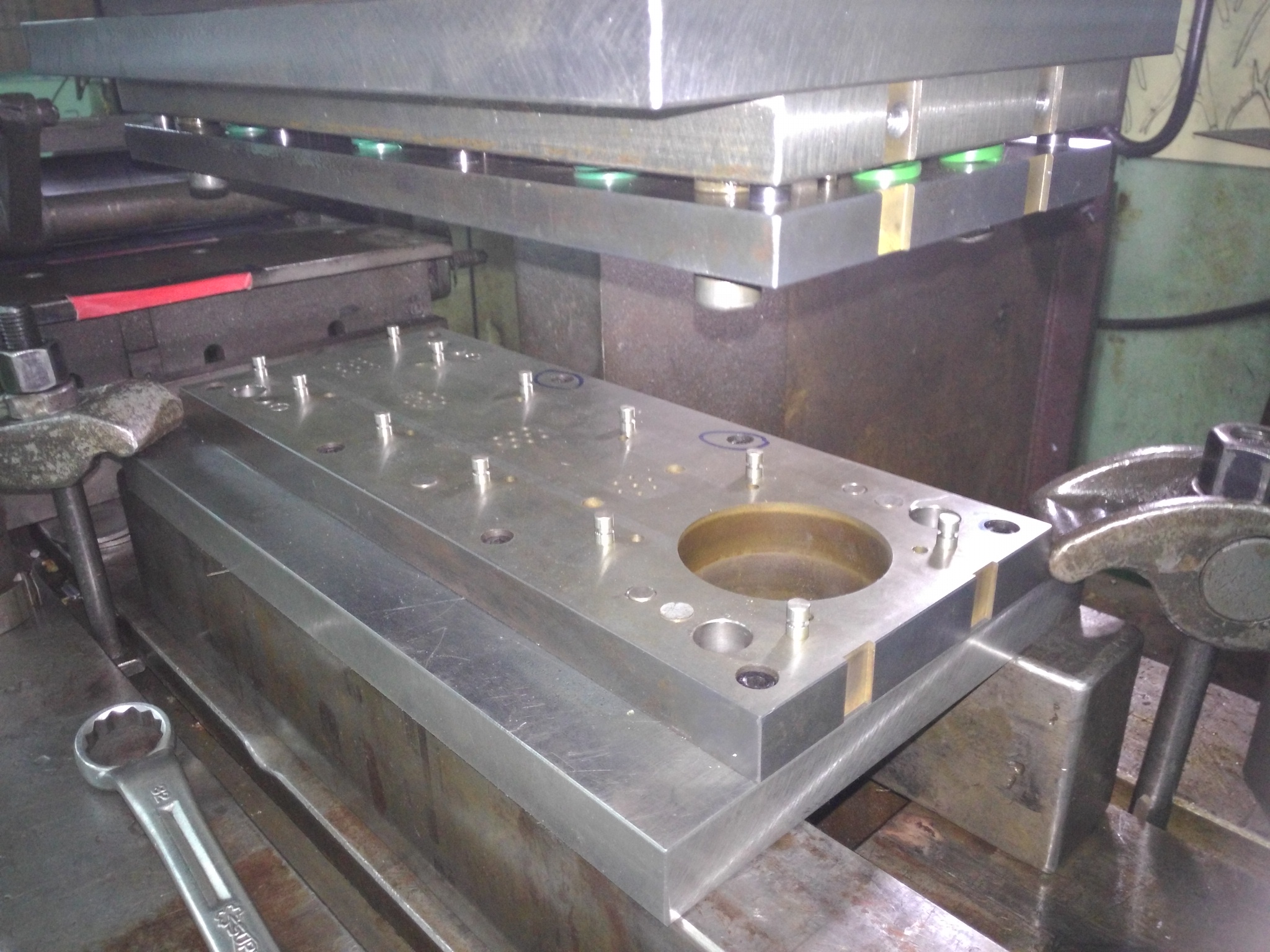

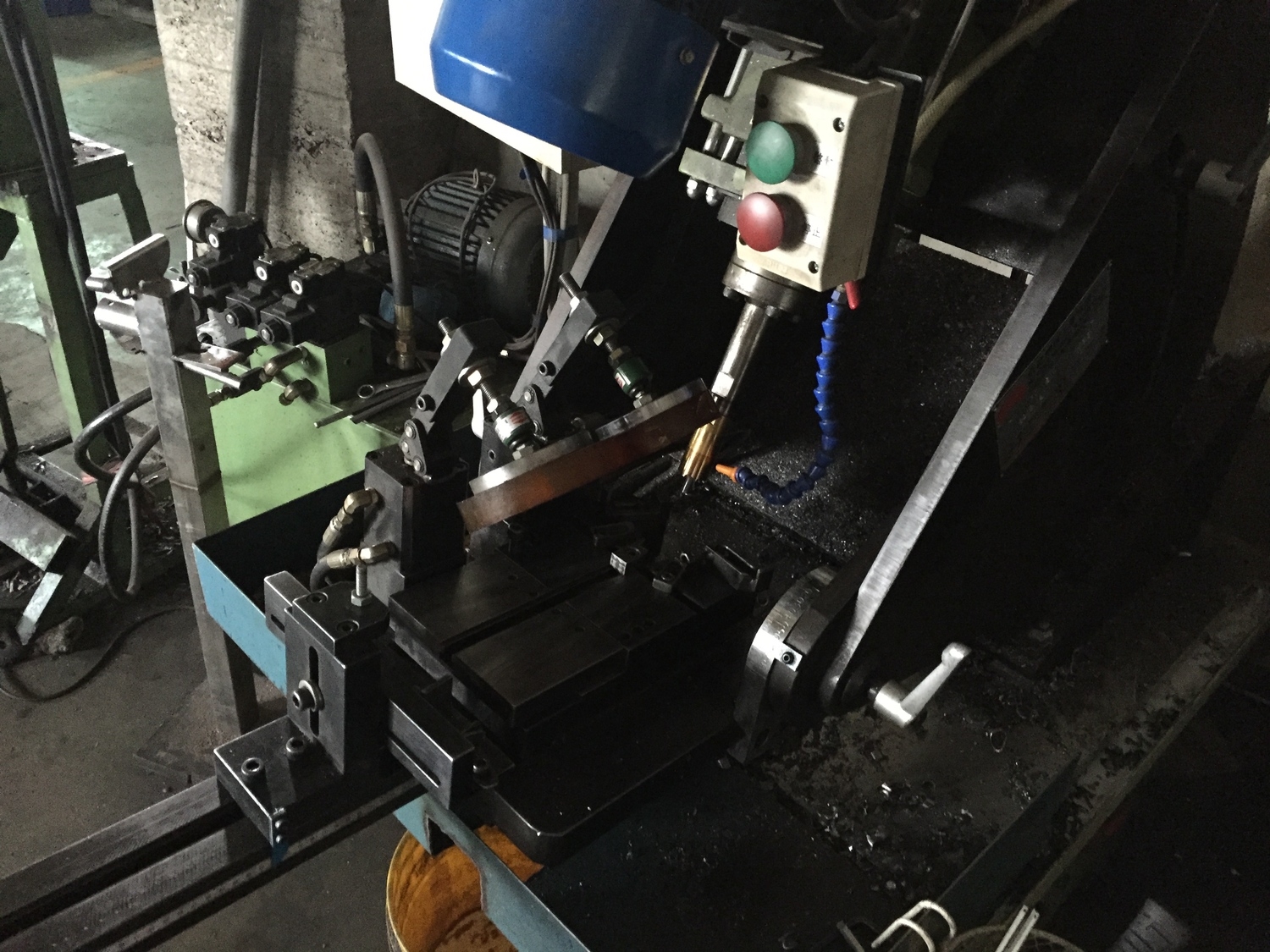

- Both the speaker nuts and screws are tiny. Do we need a customized tool to help install the nuts into the speaker assembly fixture? Is there some way that we can orient or direct the nuts and screws so that they're easier to grab and put into the assembly?

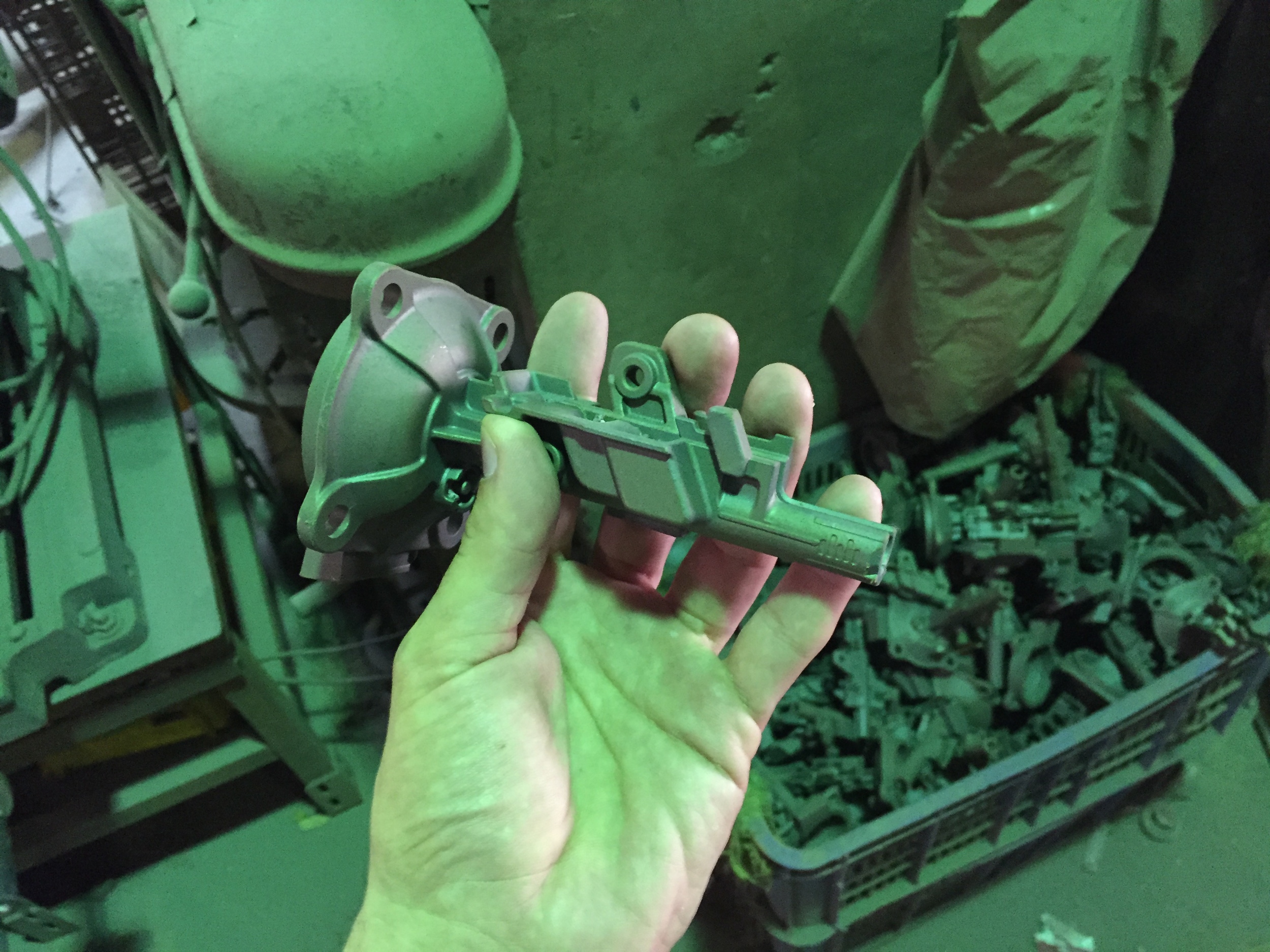

- Putting the lid onto the assembly can be a bit wobbly - especially because the lid spacer tends to swivel around while you're putting the lid on. Do we need a separate fixture or tool to hold the spacer in place while the lid is being screwed on?

- How long will the little hex recesses in the speaker assembly fixture last? We need to put a bit of torque on the screws, and I'm concerned that the recesses will strip out after not too many units.

- How do we store the potentiometer washers so that they're easy to pick up and install? The washers are pretty thin, and they're kind of hard to handle.

So, that's a pretty good list. But that's just what I *know* that I don't know; I'm sure there are many other questions that I *should* be asking.

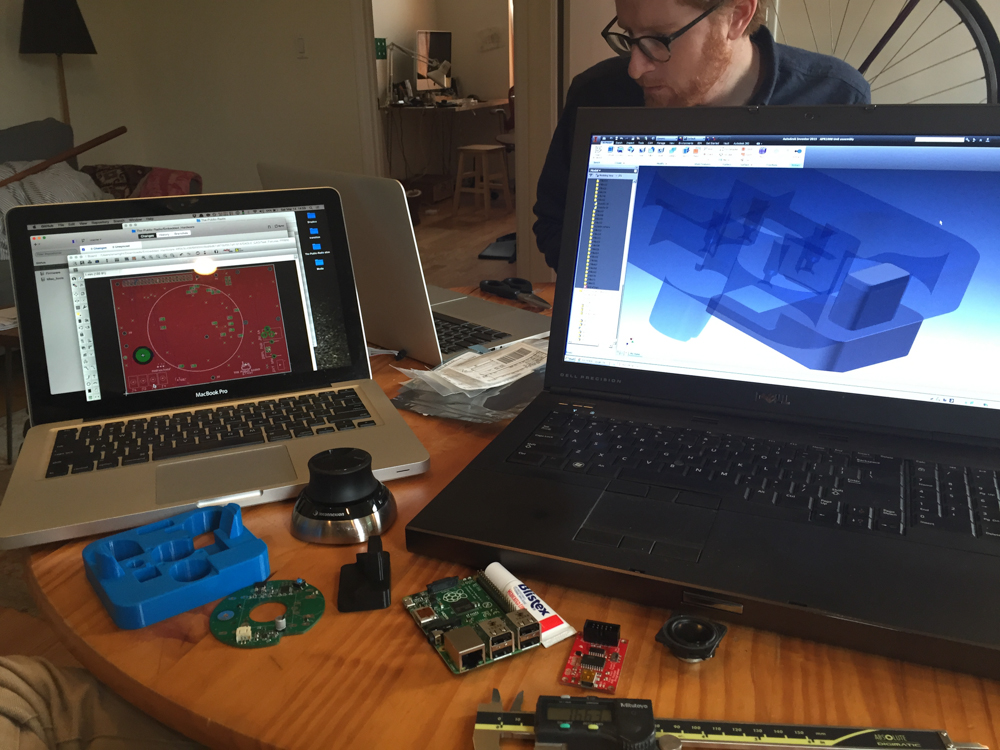

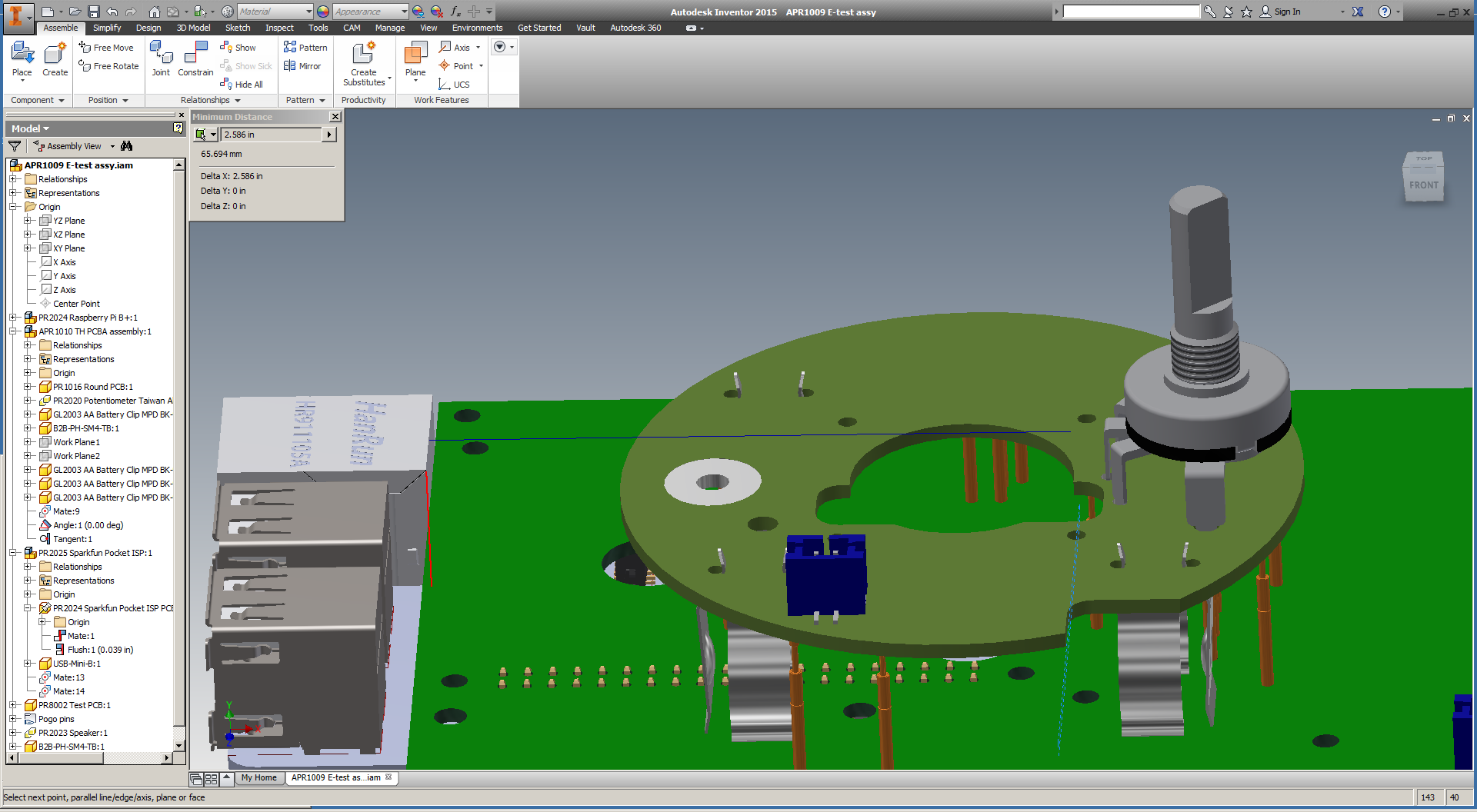

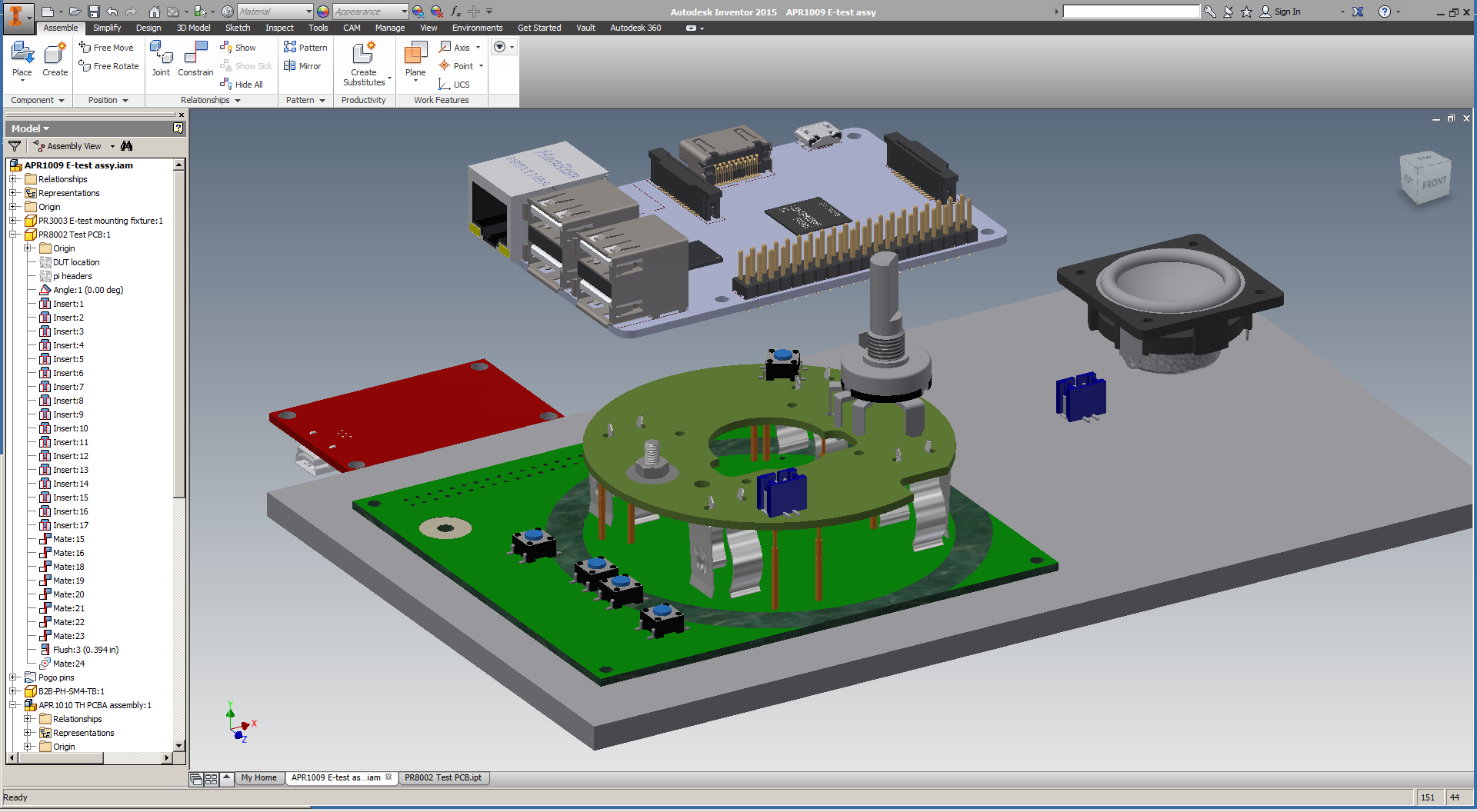

While I'm trying to find those questions, Zach will be leading the effort to get our tuning & shipping procedure mission ready. There, we had a *great* advance yesterday: Jordan found a way to get our Raspberry Pi tuning fixtures to actually broadcast audio on the FM spectrum. We'll use that feature to test every single radio we ship: after the radio is tuned, the Pi will start broadcasting the default Cisco hold music on the same frequency the radio was just tuned to. If you don't hear Opus Number 1 when the tuning is complete, then something's wrong.

So. By this time tomorrow, we should have about 70 mechanically assembled (and possibly tuned) Public Radios. We won't ship them immediately - our jars haven't arrived yet - but everything we learn will be immediately turned around and improved for the next time we build radios - probably a week from now.

Fun.