Getting this kind of picture from a supplier is *so* reassuring - and pleasant.

Diff Gifs

Inspired by a tweet by Chris Loughnane, I decided to make a visual history of the EAGLE CAD commits that Zach & I have made to The Public Radio's Github since the beginning of December.

The schematic changes are pretty subtle:

The layout is more dramatic. Partly that's because of the shift to rectangular dev boards, but if you look closely you can see that a *lot* of stuff has moved around:

Incidentally, someone - Cadsoft? Github? - should make an automated way of generating these things. They're so useful!

Anyway. We'll be ordering another round of PCBs tomorrow. Fun!

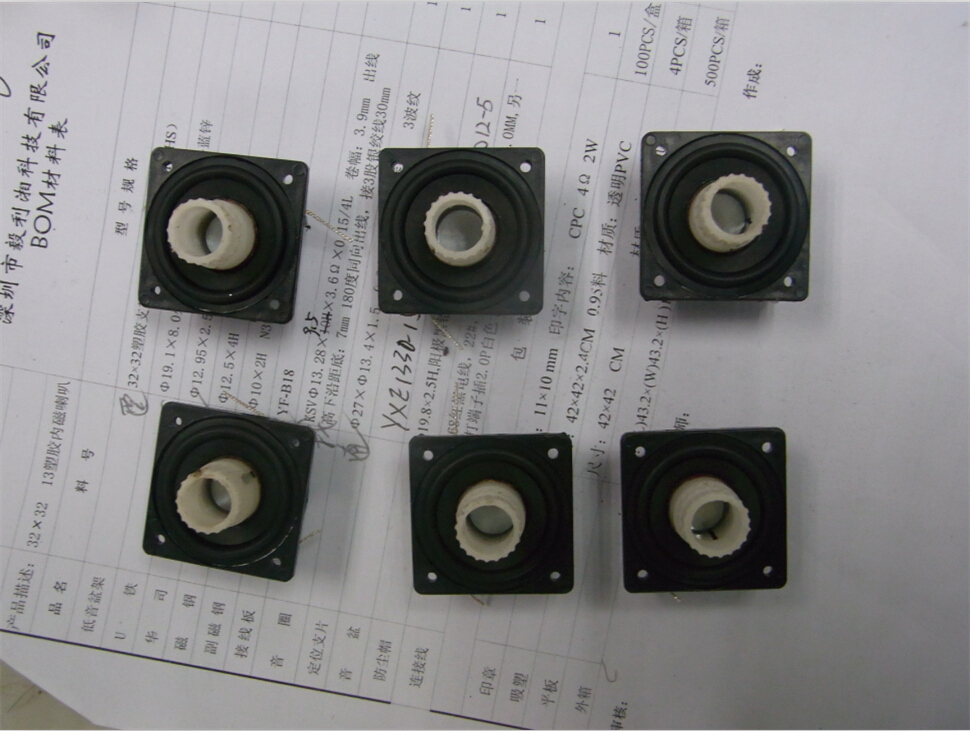

Everything I know about how speakers are made

Two photos from a speaker manufacturer in Dongguan. These constitute basically the entirety of what I know about speaker manufacturing.

So, there you go. Speakers. I'm looking to learn more: ping me if you can help (seriously).

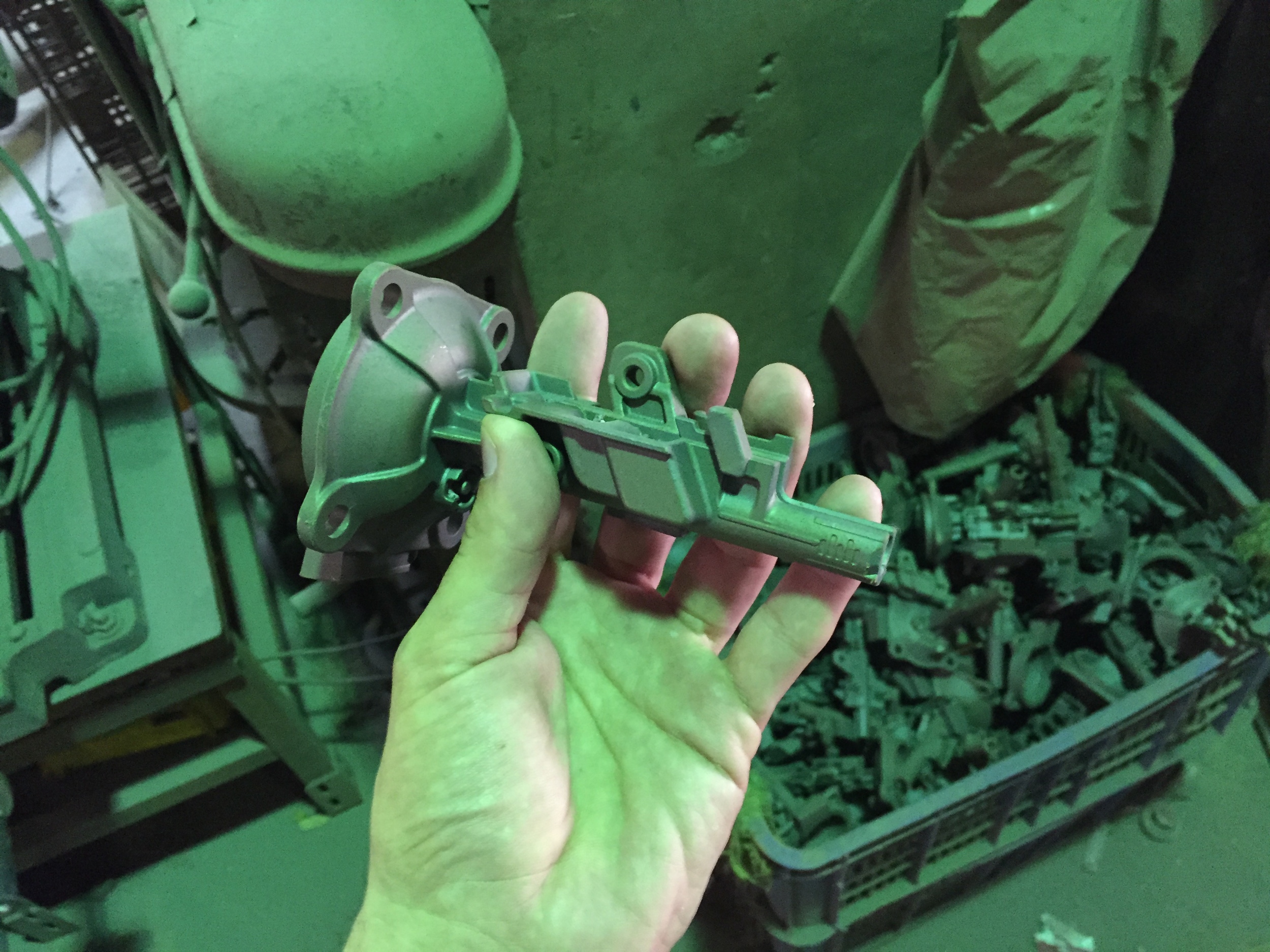

Notes from an investment casting factory in Taiwan

In October, I visited a Taiwanese investment casting shop with Brilliant Bicycles. It was *great.*

We started in the wax casting room. Here, aluminum molds are used to cast wax positives, which basically resemble finished parts:

Then we moved to wax tree assembly. Here, wax positives are welded (with an iron) to sprues. It was a really quick process. On one side there was a guy molding the sprues themselves:

And on the other side they're welded to parts. The whole room was air conditioned and very cool (it was hot outside), to keep the wax from melting.

Once the trees were assembled, they're dipped in clay and sand. There are a number of dipping stages, and the aggregate goes from fine to coarse. First comes a liquid dip:

Then a dry aggregate, which is continuously shaken to make the process easier:

This is one of maybe three areas where dipping was happening:

Then there were a bunch of dipped tree drying racks. The dipped trees need to dry before they can move forward in the process.

Then there was a big room full of kilns, where the trees were fired and cast. Nearby were big bags of raw material - iron and alloying elements - that would be melted down to cast whatever alloy was necessary.

After the trees are baked and cast in steel, the resulting steel trees need to be cut apart:

And then the individual parts are checked in QC and cold-set into place where they've distorted:

Okay, photos:

This factory was one of the coolest shops I've ever seen. Being able to see so many steps of the process coming together sequentially was really great. So many manufacturing processes happen in a distributed, disjointed manner; it was fun walking through this shop and seeing parts be transformed from wax to steel as we went.

Notes from a bicycle assembly shop in Taiwan

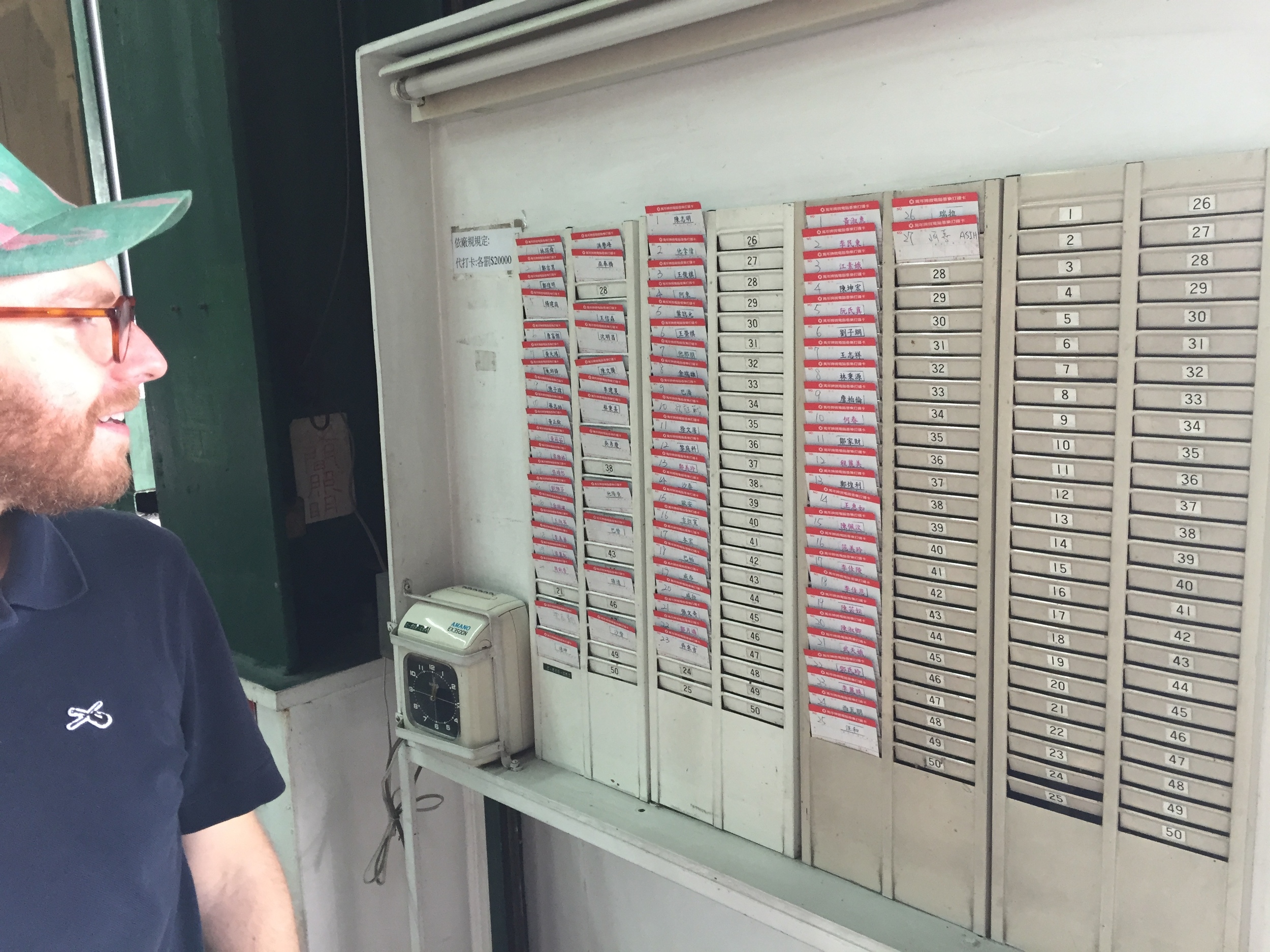

Last October I visited Universal Speed, the assembly shop that Brilliant Bicycles are built by. A few notes:

- The dedicated tooling to do frame prep operations (bearing pressing, etc) was *cool.* Most of it was made by Shuz Tung, a Taiwanese company.

- The wheelbuilding line was the single biggest part of the operation. The truing machine especially was impressive (videos below).

- They build everything upside down! I can't imagine doing this, but the advantages re: not touching the paint are really big.

- It was a really big facility - tens of thousands of square feet.

- The moving assembly line was fun.

Here are the wheels being built:

And here's the wheel truing machine in more detail:

Here's the whole shop (ish):

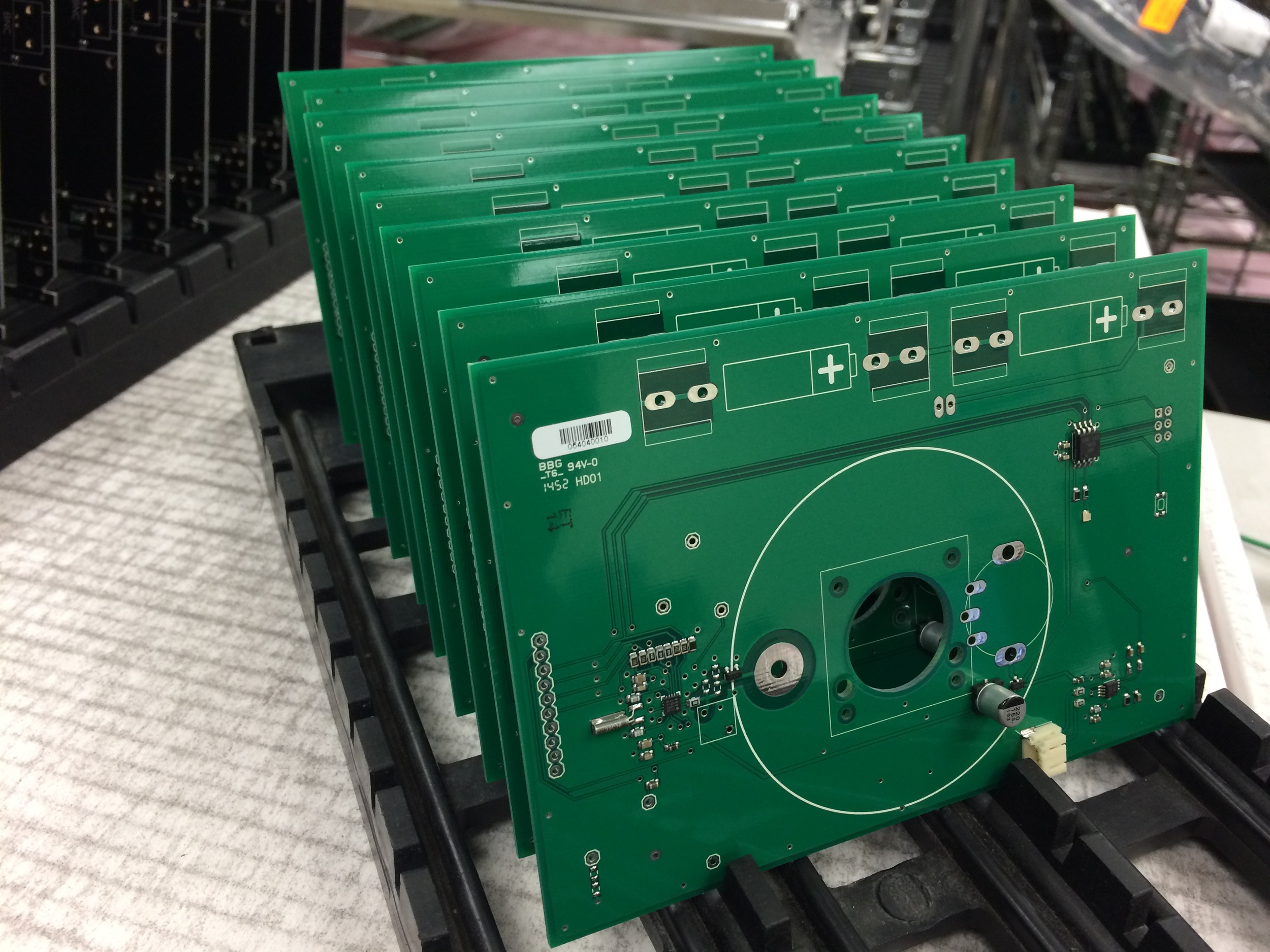

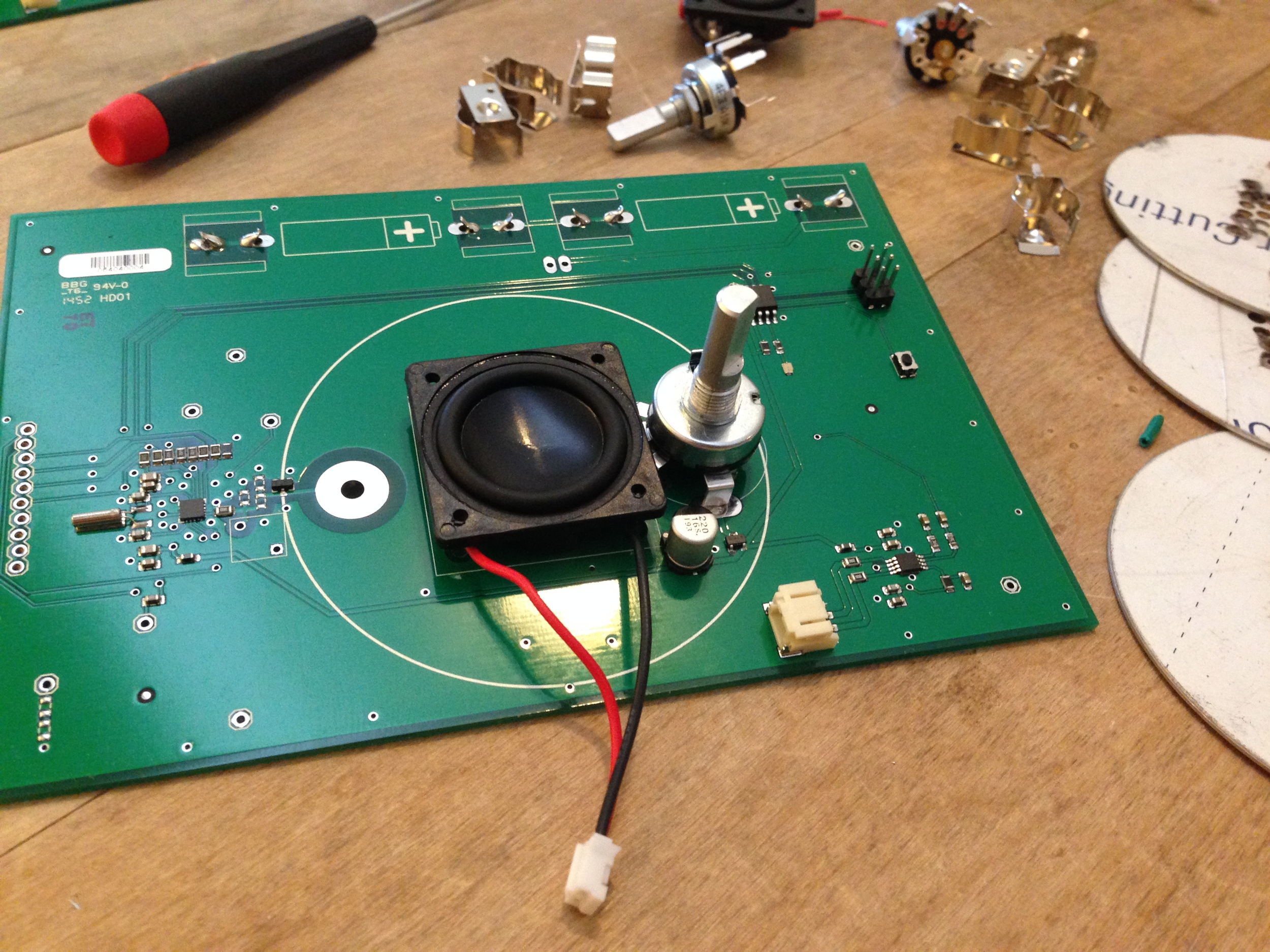

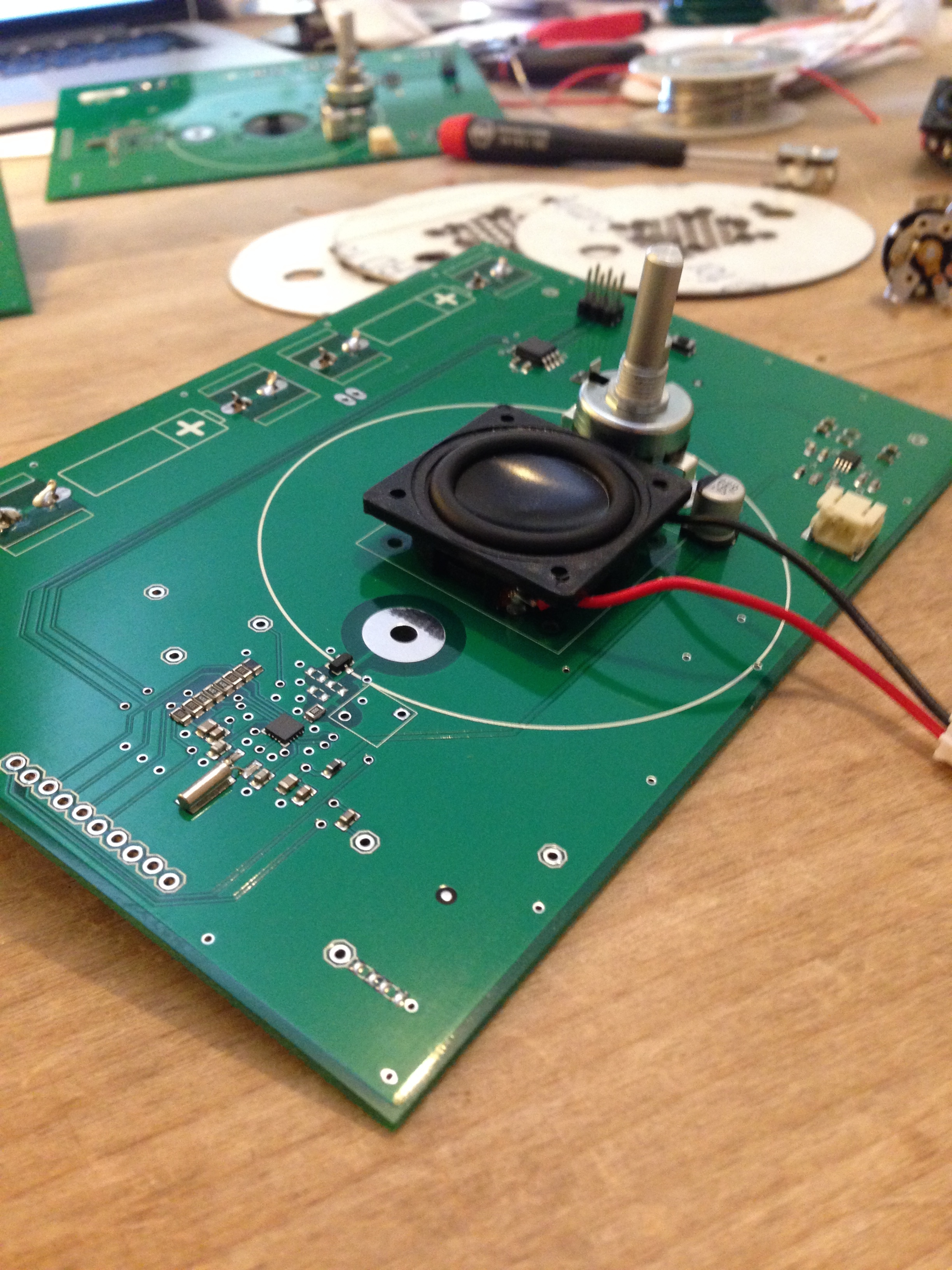

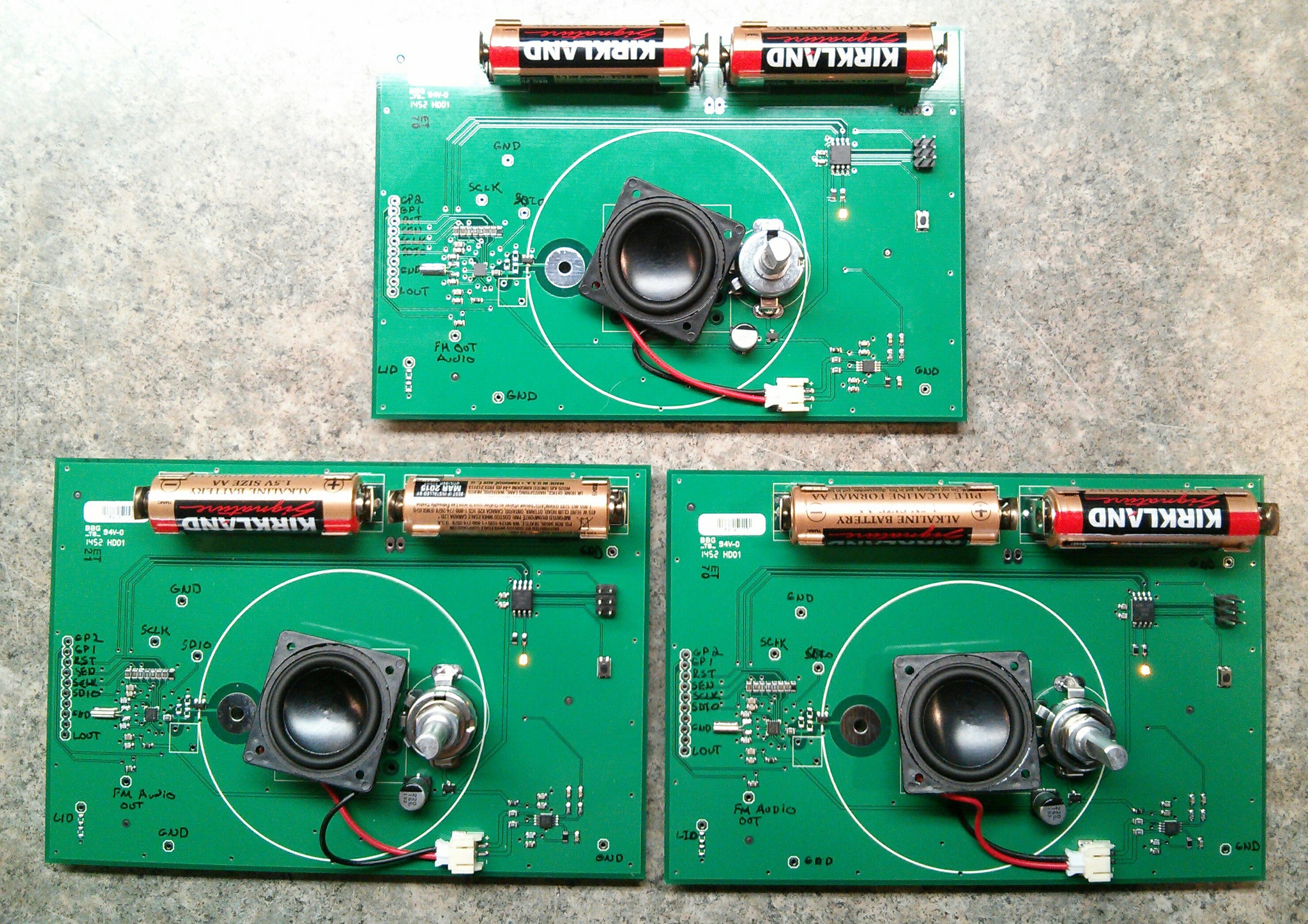

The Public Radio dev boards

Over the past month, we've been hustling *hard* to re-engineer The Public Radio's circuit design. We knew we needed to do this in order to transition to a digitally tuned FM IC, and budgeted enough time to go through two or three final prototyping rounds. The first round was the hardest - we wanted to be making as few changes as possible on the second, so balancing speed and accuracy this past few weeks has been a real challenge.

But it's coming together well, and we received our first development PCBs the other day. Our prototyping partner, Worthington Assembly, did all of the SMT components, and Zach added the thru-hole parts on Thursday.

We already found a few minor errors - two of our part footprints were a bit off - but they're all easily fixable and not an issue for working on the development boards.

Over the next week we'll be putting these through the ringer, and making any small changes we need to make the circuit fully optimized. Then we'll shrink the board back down to production size and will get one more prototype run built before placing our final orders.

More updates soon!

First successful Topper build

After upwards of 10 different build configurations, my seatmast topper finally completed without any big hiccups. Late yesterday I got these images from DRT Medical, my prototyping partner:

I'll be posting a bigger update (with progress photos & descriptions of the build process) soon.

A year of my mailing list

I've been doing my weekly mailing list (which you should sign up for!) for a little over a year.

The first four issues were sent on 2013.11.20, 2013.12.26, and 2014.01.10. They had no subscribers and were pretty loose. The first issue claimed its purpose to be:

To be useful. To connect. To tell you about things that matter to me.

Furthermore, all of the first four issues included a version of the following:

"If you're going to make a mailing list, at least make it a self-aware one."

— Me, like a month ago, when I first set this mailing list up.

Today, I have 194 subscribers. I'd say that I know about a third of them personally, but about half of those people I know mostly through the mailing list itself. In 2014.04.12's issue I added a note at the bottom of each email asking the people I send it to to have coffee with me, and through that I've made a number of new friends.

Here you can see the list growth over time, plus open & click rates by issue:

My workflow is as follows: I get links from places (details below). I add them to Pocket. I read them on my daily commute, which is a predictable 30 minutes twice daily. If I like something, I star it. Then an IFTTT recipe grabs the link and emails it to me. When I'm back at my computer (usually the same day), I open the link up and add it plus a short description/observation to that week's campaign.

My sources fall in four big categories:

- The first (and most prevalent) is RSS. I use Digg Reader, and go through between 50 and 100 posts a day - almost never reading them in browser, almost always saving them to Pocket.

- The second is Twitter. I follow about 600 people, and save a handful of links per week to Pocket there.

- The third is through one of the companies that I work & hang out at. The Undercurrent Slack channels give a few articles per week, as do Gin Lane's email chains, which I'm on. I also get a lot of links from Kane & Adam at Brilliant Bikes.

- The fourth is through subscribers. I get a few emails per month from people (often friends) who subscribe to The Prepared and think I'd be interested in something.

At any given moment I usually have between 40 and 80 articles in Pocket, and I churn through them pretty quickly. I organize my Pocket list LIFO, which means that some longer articles get stuck in the queue for a while. I'll usually try to attack those on a long flight, or if I know I'll be in a waiting room for a while.

It's surprising to say so, but in the past year my mailing list has become arguably the single most popular and useful thing that I do. It's also something that I'm quite fond of. For one, it does a great job at incentivizing me to self-educate. But equally as important (and much more surprising to me) is the effect that it's had on my social circles. The Prepared's subscriber list continues to amaze me; I feel absolutely blessed that there are so many caring, intelligent, and interested people who bother to read it.

Thanks so much for a great year!

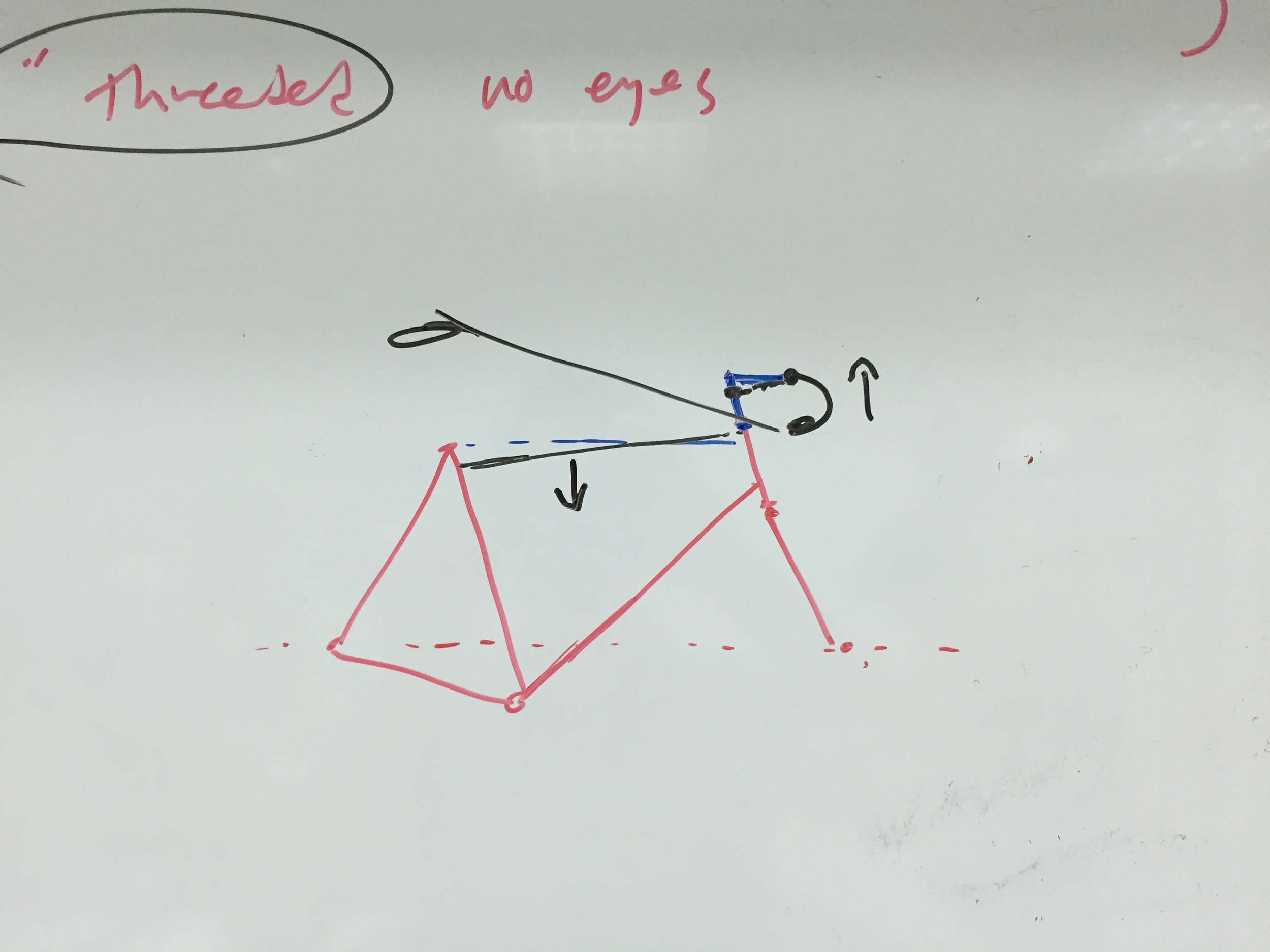

Notes from a bicycle frame factory in Taiwan

In October, I visited a Taiwanese bicycle frame factory with Brilliant Bicycles.

Photos!

The shop was 10 or 20 thousand feet. A significant portion of it was storage, and there was a smallish office area near the front door. We met the owners and had lunch upstairs above the office, which provided a nice place to take a pan of the whole shop.

The sheer quantity of dedicated fixtures here was kind of staggering. I couldn't tell (and didn't ask) but it seemed like they probably made fixtures for a lot of frame subassemblies, each of which would be dedicated to a certain frame model and size. This video shows about half of the fixtures that I saw in storage.

Frame subassemblies were tacked and stacked in tall piles. I'd guess that the main frame fixture took an hour or two to set up, but at that point the tacking would go quickly. The subassemblies would then be moved down the welding line, comme ci:

The quality of the welding here was very good. There were a bunch of guys doing TIG and a few brazing dropouts. They all had big fans running, but it was still hot. We were around right as their lunch break began:

As with the fork factory we visited, the alignment process was *so* cool; unlike the fork factory, I didn't take a video of it :( As I watched the one alignment guy go through his routine, I couldn't help but compare it to my old Traffic Cycle Design alignment setup. This guy was doing a full, thorough frame alignment, *and* reaming seat tubes, all in something like 2 minutes. I would have been hard pressed to do the same in a half hour.

All in all, this factory was *really* fun to visit. Its super interesting seeing someone else perform tasks that are similar to ones you've done. In all honesty, I was always really attracted to the idea of having a much larger shop setup - and one that could perform tasks much more efficiently than I was ever able to. It was fun seeing that kind of operation running in real life.

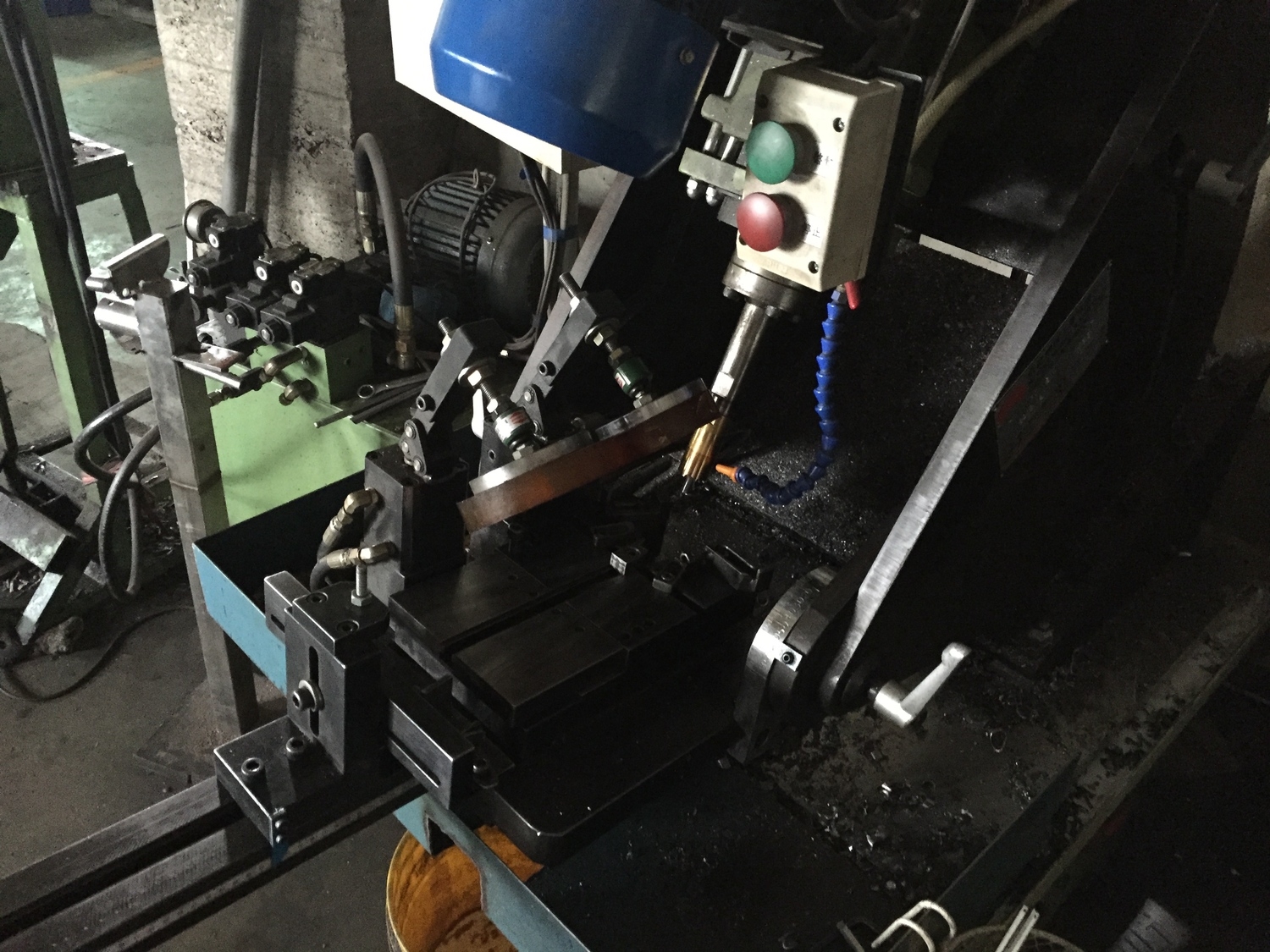

Notes from a bicycle fork factory in Taiwan

In October, I visited a Taiwanese bicycle fork builder with Brilliant Bicycles. The shop was in a totally rural area; the vast majority of land usage was rice paddies. These photos are taken from directly in front of the shop:

The building on the far left is the fork shop's storage area.

That's the fork shop on the far right.

The shop itself was a couple thousand square feet. It was rectangular, and had a single gable roof. The gable end to the east had a huge open door, and there were fans everywhere to maintain airflow; it was hot inside nonetheless. On the other end the shop adjoined to what I presume were office and a small apartment area.

A few notes:

- Fork legs came in straight. Unicrown fork blades were bent in house from straight legs.

- The dropout end of the fork blades were swaged, slotted & brazed first. I don't have any pictures of the process but it was pretty cool - the brazing especially. They had a big turntable, maybe 6 feet in diameter and with a few dozen fixtures around the perimeter. Each fork blade had powdered flux + brass filler shoved down from the top, and the dropouts were fluxed with paste. The whole assemblies snapped into the machine and sat on an incline, so that the dropouts were on the perimeter and the blades angled up and to the center of the turntable. Then the whole thing was spun very slowly, and a single flame at the perimeter would heat one of the dropouts up until the brass melted and flowed, and then the turntable would advance to the next dropout.

- Then the blades would be assembled into crowns. The whole crown was brazed at once with the tips pointing up (video below).

- Then the forks would be raked. That machine was really cool too - there's a photo below.

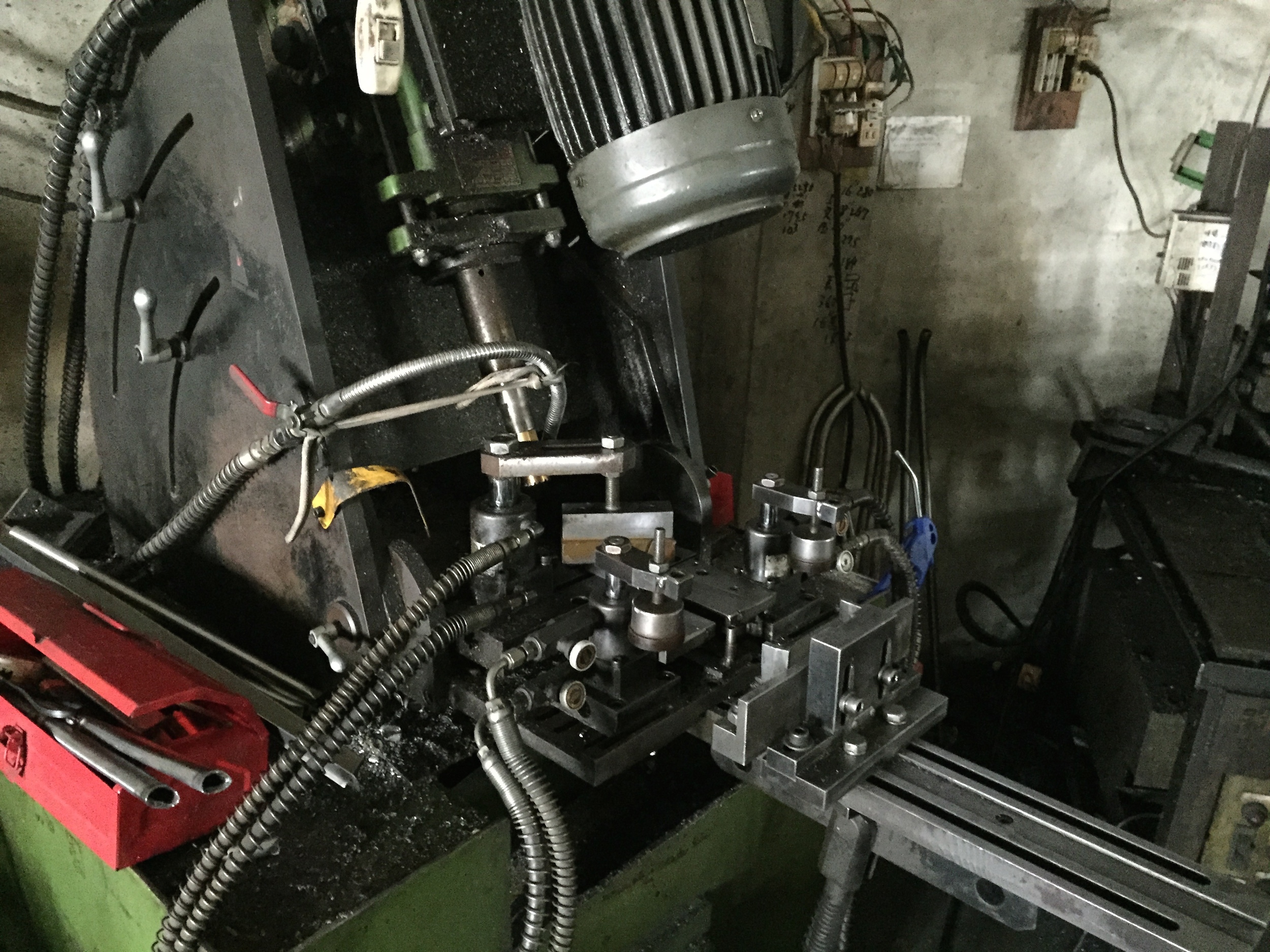

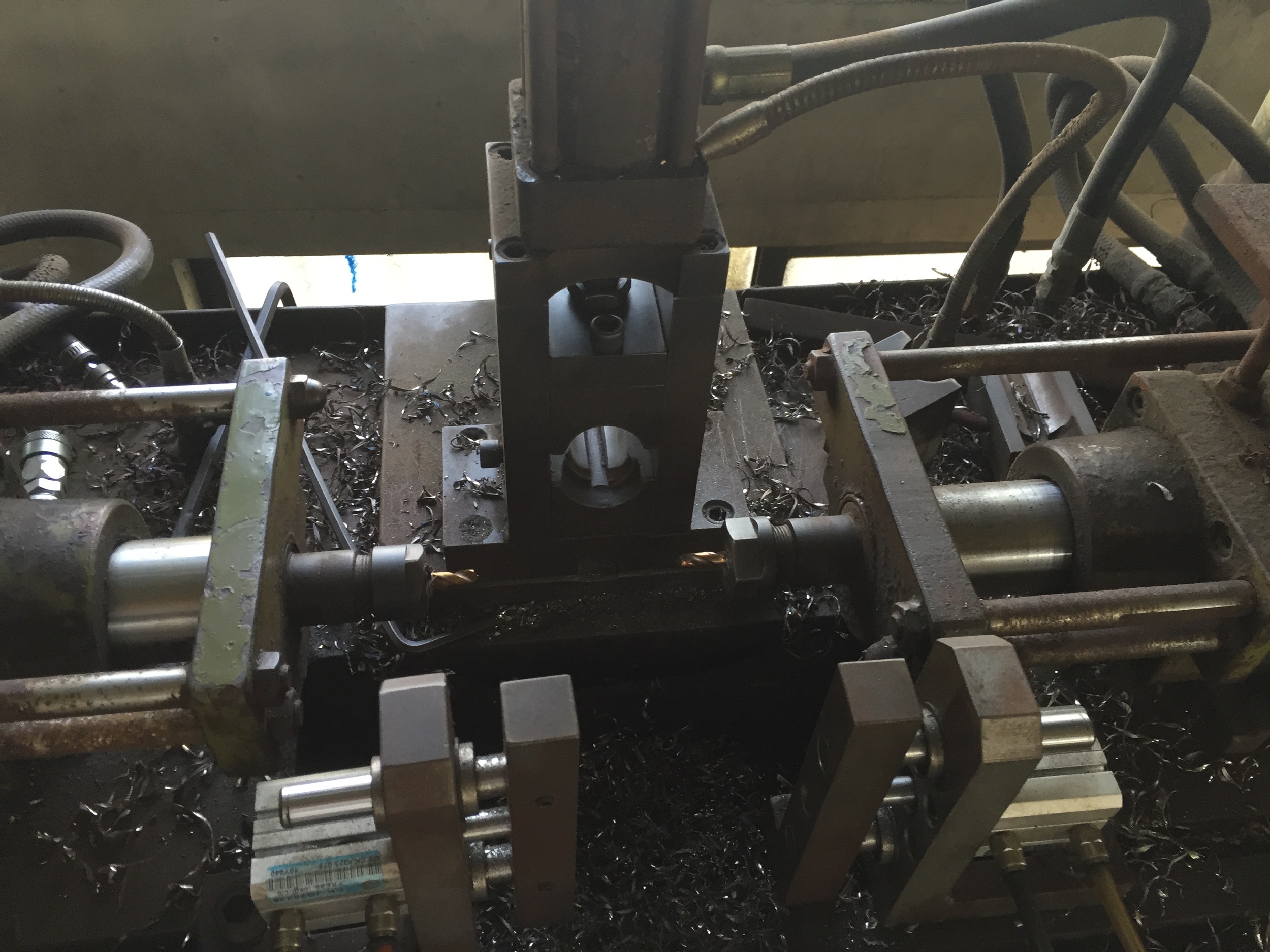

- Then the crowns would be drilled & counterbored on dedicated fixtures. They had two or three small drill presses set up to do this, and they were running full time while we were at the shop.

- Alignment was awesome. The guy was really quick with the whole process, and it was a fluid and rhythmic operation. Video below.

- It looked like they did mostly lugged forks, but that could have been just the time we visited - there was a TIG setup there, but it wasn't being used while we were there.

The shop manager was enthusiastic about showing his brazing skills. I was surprised that they brazed them before bending, but the process actually makes a ton of sense in their environment.

The fork alignment process was *awesome.*

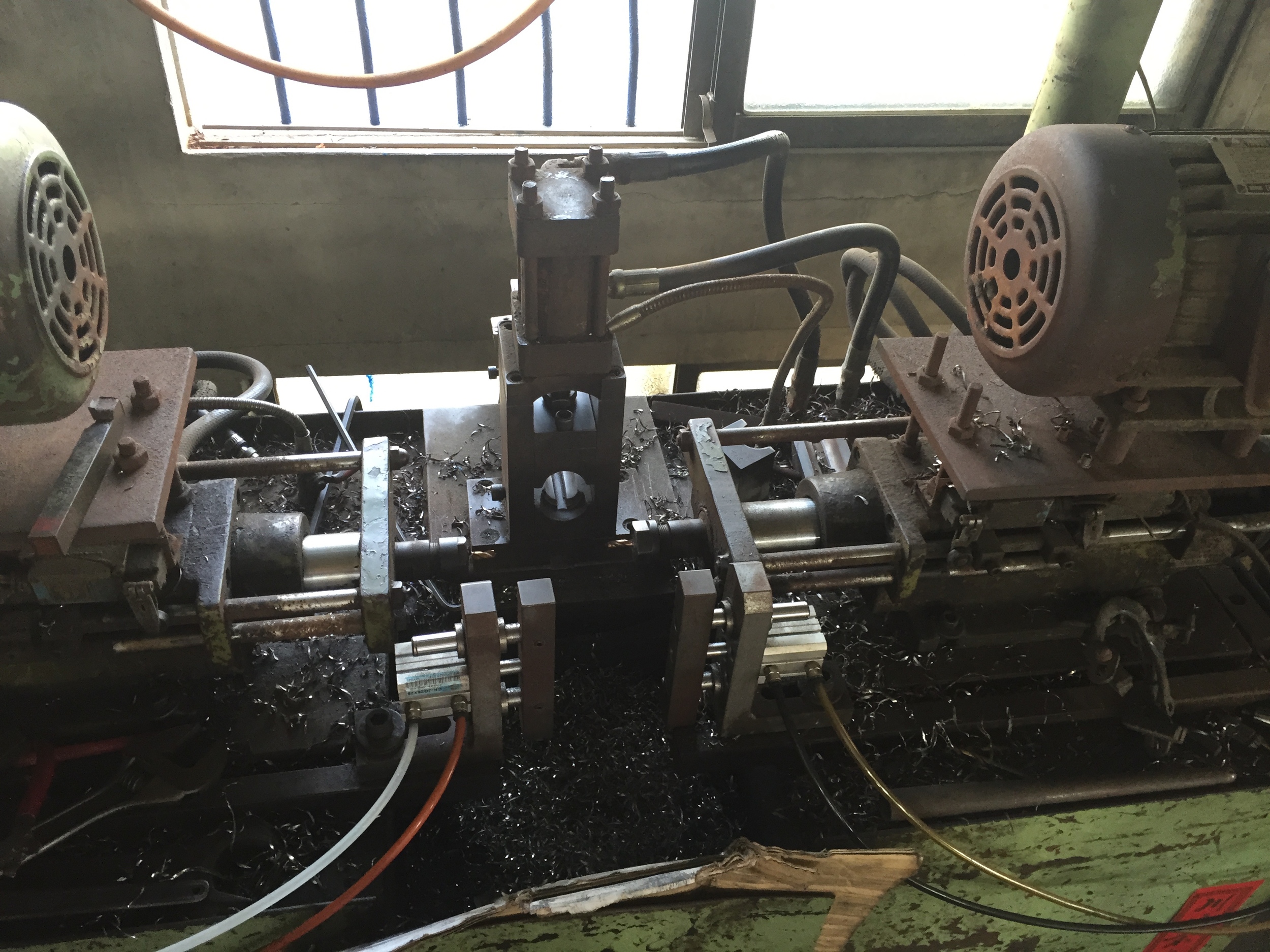

Here's a pan of the whole shop:

I liked this shop a *lot.* As we were leaving, the owner commiserated with April that though he had worked there his whole life, he didn't think his children would want to do the same. Building bike forks isn't the dirtiest job in the world, but it isn't the cleanest either. Furthermore, these are good quality but relatively inexpensive steel forks; the product is essentially a commodity, and it isn't exactly prestigious work. I wondered aloud if they could make more money, and have slightly nicer working conditions, if they moved to carbon fiber products. The problem with that is that although the product is a substitute, the skills and equipment needed are quite different. In the end, it might be more fruitful and no less difficult for the next generation to change industries altogether. But anyway the owner was relatively young himself, so it could be decades before it changes at all.

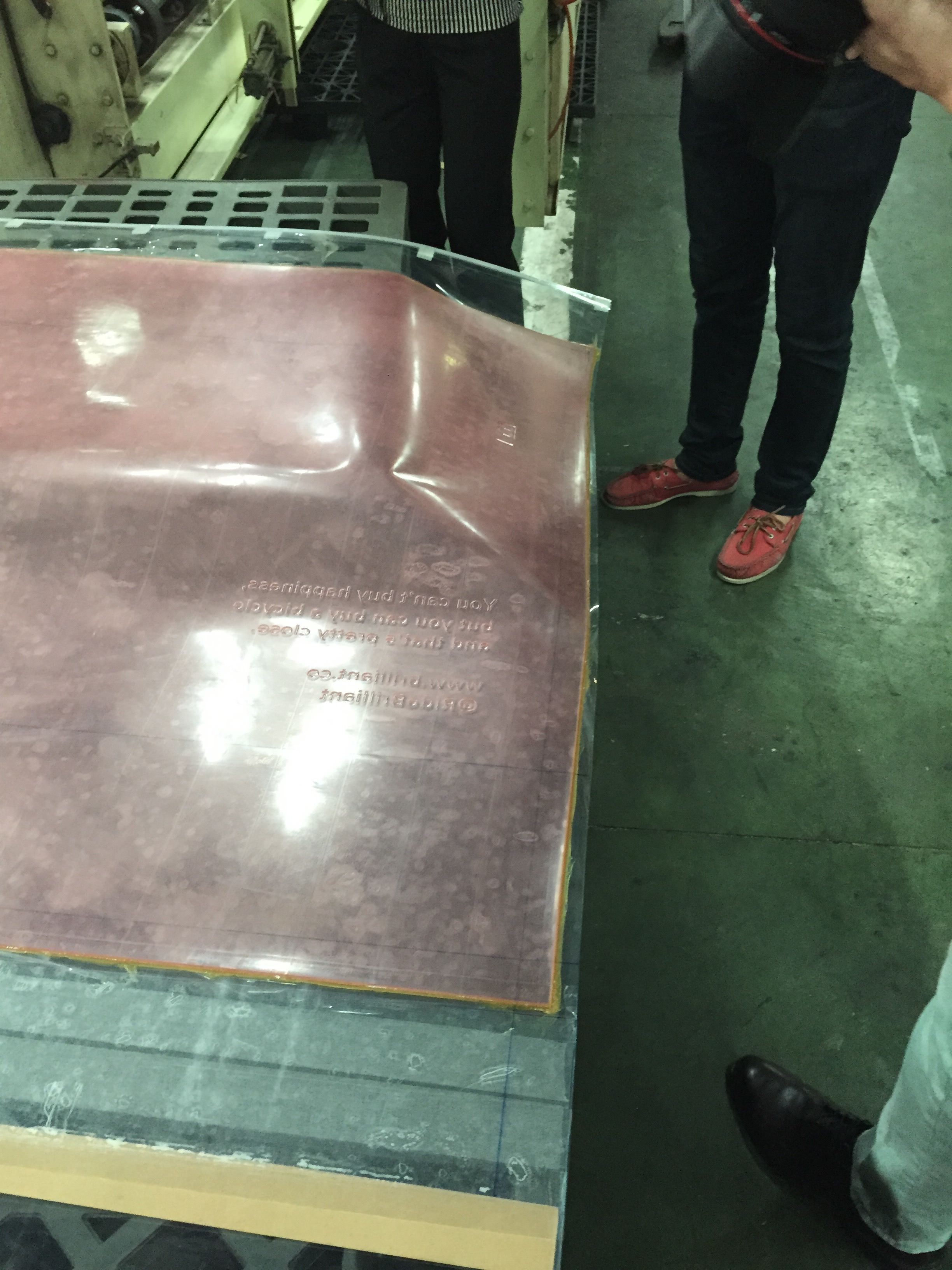

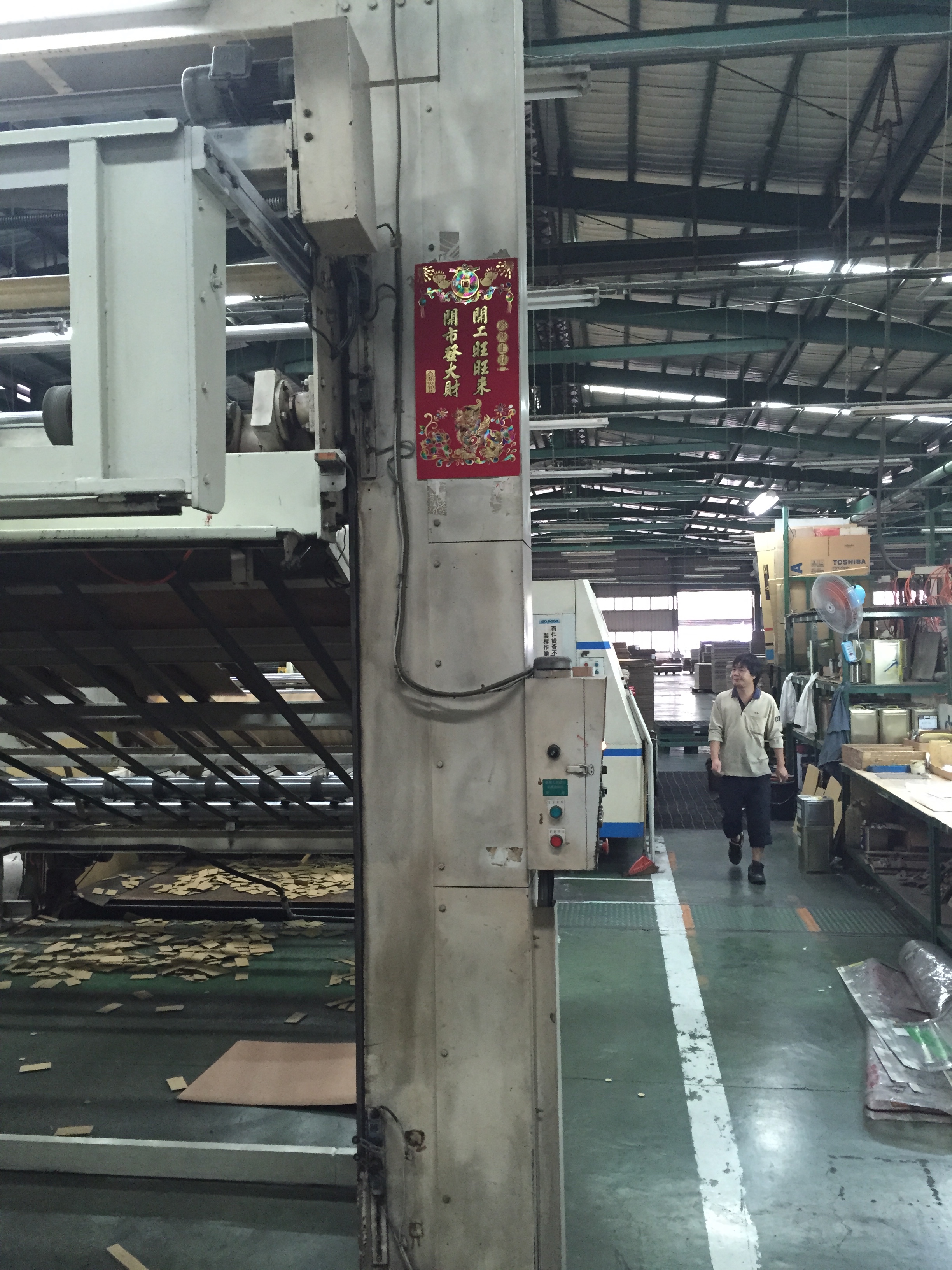

Notes from a cardboard factory in Taiwan

In October, I visited a Taiwanese cardboard factory in Taiwan with Brilliant Bicycles. A few notes:

- Paper comes in, finished cardboard boxes go out.

- The paper rolls come in various shapes, sizes, and presumably thicknesses, but they're generally *huge* and brown.

- The whole place, but especially the sheet assembly line, was really loud - one of the loudest places I've ever been.

- There are three big portions of the factory: the sheet assembly area, the box printing & slotting area, and *lot* of cardboard sheets stacked up around the factory.

- The sheet assembly area takes brown paper rolls, each of which weigh upwards of a ton, and transform them into cardboard sheets. The machine that does this is huge - probably 20 feet wide and maybe 200 feet long. The cardboard we saw getting made was 5-ply, which has three flat sheets (the two faces and one in the middle; think the slices of bread in a club sandwich) and two corrugated sheets (think the bacon, turkey, etc in the same sandwich). Presumably the exact specifications of the corrugation (e.g. its thickness) affect the structural properties of the cardboard; I think the sheets we saw getting made had thicker corrugations (maybe for the inside of the box) on one side and thinner on the other. Anyway, the sheet assembly machine takes five big rolls of paper and spools them out together, corrugating them as necessary and applying adhesive between the sheets. Then it applies pressure and feeds the whole continuous sheet through a pair of heated plates, which help cure the adhesive. Then it trims the sides off, slots the sheet in half lengthwise, and then chops each half into sheets of the appropriate size for what they're making.

- Then the sheets are stored in stacks around the shop. There were a *lot* of stacks of cardboard sheets - a large portion of the factory was just storage.

- The box printing and slotting section was a bit more disperse. There were a bunch of machines to perform these steps; some did one or the other, and some (including the one that Brilliant's boxes were made on) do both. The printing is done with big, colorful, silicone stamps. Most of these were presumably made out-of-house, but there were some (like the "no knives" and "fragile" stamps) which seemed to be standard and were being assembled onto clear plastic sheets (mylar?) by people in one area of the shop. We didn't see steel rule slotting dies being made (perhaps they were outsourced), but they were stored all over the shop. There were a bunch of varieties of those - some were used in manual die presses, and others were loaded into slotting machines and then operated automatically.

- A bunch of work was put into aligning the stamp and dies in the machine. If I were to guess, I'd say 5-10 sample parts were made before the alignment came out right.

- Once the alignment was right, the boxes came out really quickly. We were only having a few hundred boxes made; I'd guess they'd be done within a few hours.

The place was huge - one of the single biggest unobstructed spaces I've ever been in:

The cardboard printing & slotting machine was really cool. There's nothing like a black box that takes raw material in and spits out a useable object on the other side:

Seeing general purpose manufacturing is always a lot of fun. Cardboard boxes are used *everywhere.* Having seen how they're made gives valuable perspective on something that's on basically any BOM.

Notes from a tire factory in Taiwan

In October, I visited a Taiwanese tire factory in Taiwan with Brilliant Bicycles. I didn't take many photos, but do have a few notes:

- The factory made a bunch of solid tires for forklifts and other equipment in the front.

- In the back were two sides: One for bicycles, the other for scooters and other larger pneumatic applications.

- The shop did *not* make their own nylon cord for tire casings; they purchased that from a vendor. The cord comes in a wide sheet, is cut on a bias and put together into a long strip (video below).

- They also did not make their own kevlar (foldable) tire beads. Apparently all of the Taiwanese tire shops (there are a few) purchase these from one single supplier.

- They do make their own steel beads. Wire is straightened, doubled up, and wrapped into a loop with a bunch of unvulcanized rubber and bound together into a single unit.

- The machines they use to assemble the tires - casing, bead, and tread - are *really* cool. There's a decent video of the process here.

- Tread molds seemed eminently reasonable - they only cost a few thousand dollars. The uncured and relatively shapeless tires are put into molds, where pressure and heat form the shape and cure the rubber.

Here's a photo of the front of the shop, where solid tires were being stored:

And here's a video of nylon cord being cut on a bias and spliced together:

And, two random photos: One of a magazine in the factory's conference room, and one from the restaurant that the (extremely eager) factory manager took us to for lunch:

A few notes from Boeing

Last week I visited Boeing's Everett, WA factory, and saw the 747, 777, and 787 lines. I couldn't take pictures and had no time for notes, but I did have a few observations/factoids that I wanted to record:

- The tour was *not* free - it cost $16 if you reserved ahead of time, which I did. They do tours every hour or two, and my group filled two buses - probably 50 or 60 people in total.

- The Everett facility is the largest building in the world by volume. Our tour guide said that last year someone in China opened a mall that's bigger by floor space, but that Boeing is expanding to get that title back too. I assume that that is a) hyperbole, and b) true nonetheless.

- The facility employs something like 41,000 people on a daily basis. Fuck.

- The 787 is pretty cool. It's made mostly of composites - presumably carbon fiber + epoxy + some mix of aluminum, titanium, ceramics, and other metals (there's a good explainer on its construction here). Its wings can flex something like 21 feet vertically during flight, giving it a lot more vertical compliance and presumably making the ride a lot smoother.

- The 787 is significantly smaller than the 747. Boeing is proud of this, and scoffs at the Airbus A380's enormous size. They're trying to push away from the hub-and-spoke model, and encourage airlines to purchase more planes, which will fly a wide variety of routes at relatively high usage rates. Since it's really hard for airlines to make money when flights aren't full, this strategy seems to make sense - it's *really* hard to fill an A380 (they fit 853 passengers!), so why not just buy two or three 787s (242 to 335 passengers) and fly them fully booked?

- Planes are purchased without engines or seats; those need to be bought separately, and Boeing will install them at the end of their production line.

- I asked what engines Boeing uses, and was told that while the makers vary by model, Boeing typically uses a mix of GE, Rolls Royce, Pratt & Whitney, and CFM (a collaboration between GE and Snecma).

- Interestingly, Pratt & Whitney (now a subsidiary of United Technologies), Boeing, and United Airlines all once shared a parent company: the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation. That company was disbanded in 1934.

I would *love* to know more about the 787 supply chain. The Japanese company that makes the prepreg, Toray, looks interesting. And obviously both Mitsubishi and Kawasaki (both big suppliers for Boeing) are fascinating as well.

Random Things in Taiwan

A couple months ago I visited Taiwan with Brilliant Bicycles, and toured a number of bike industry factories. These are my non-factory photos from the trip.

Sufficiently expert

From a Paul Graham essay titled "How to be an Expert in a Changing World:"

If you're sufficiently expert in a field, any weird idea or apparently irrelevant question that occurs to you is ipso facto worth exploring.*

* In practice "sufficiently expert" doesn't require one to be recognized as an expert—which is a trailing indicator in any case. In many fields a year of focused work plus caring a lot would be enough.

Yes.

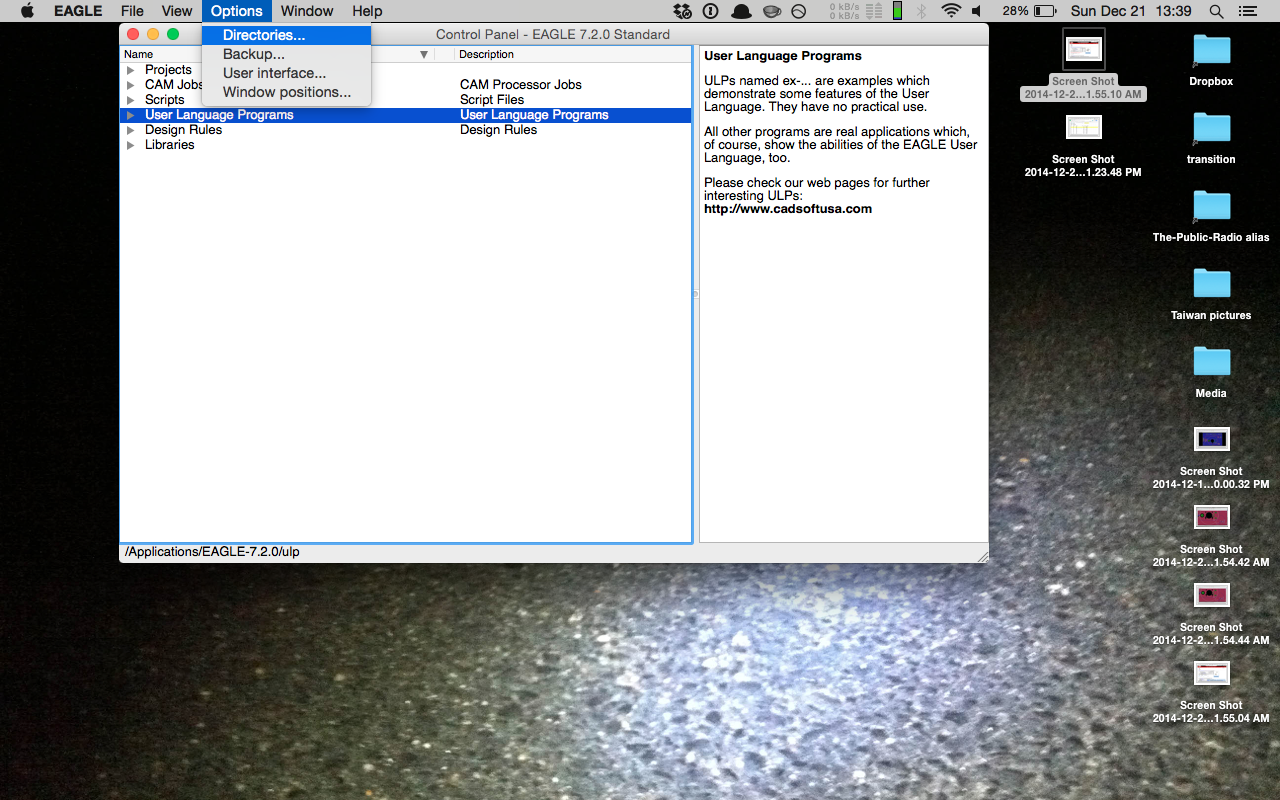

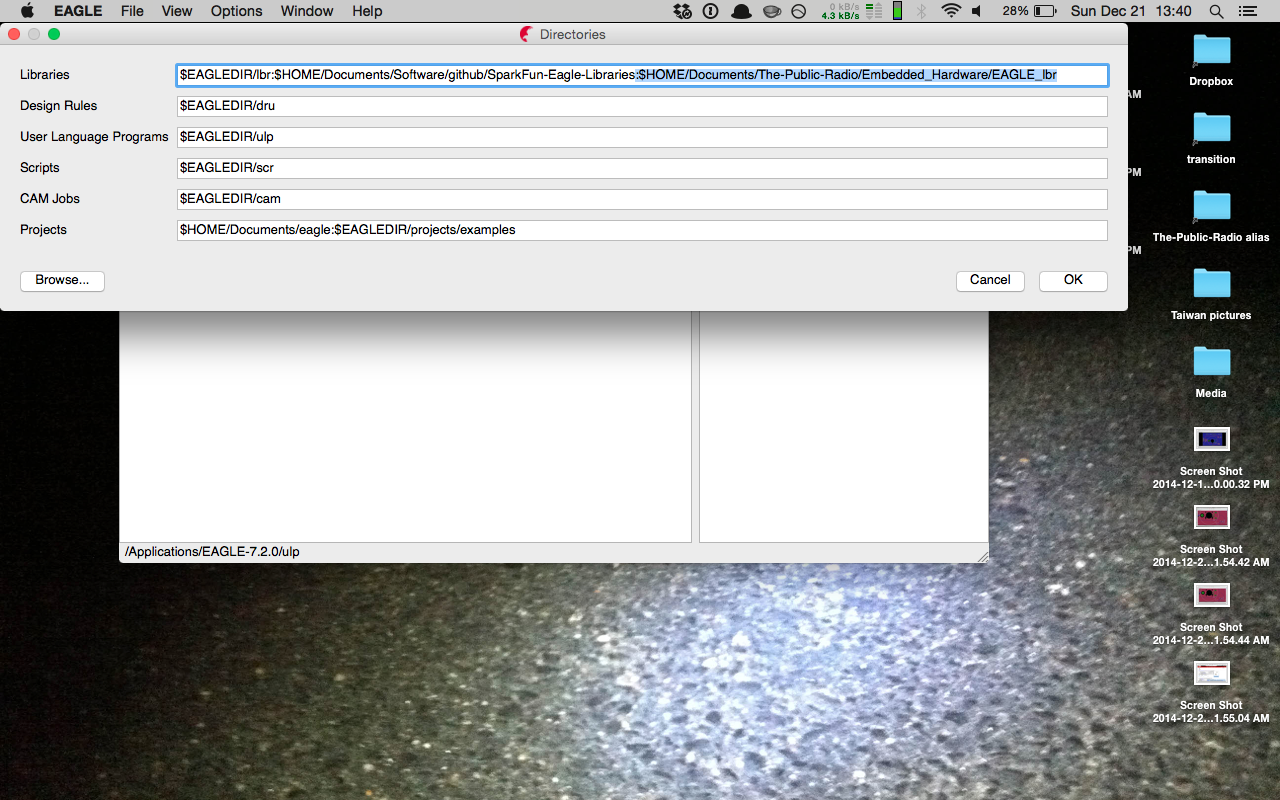

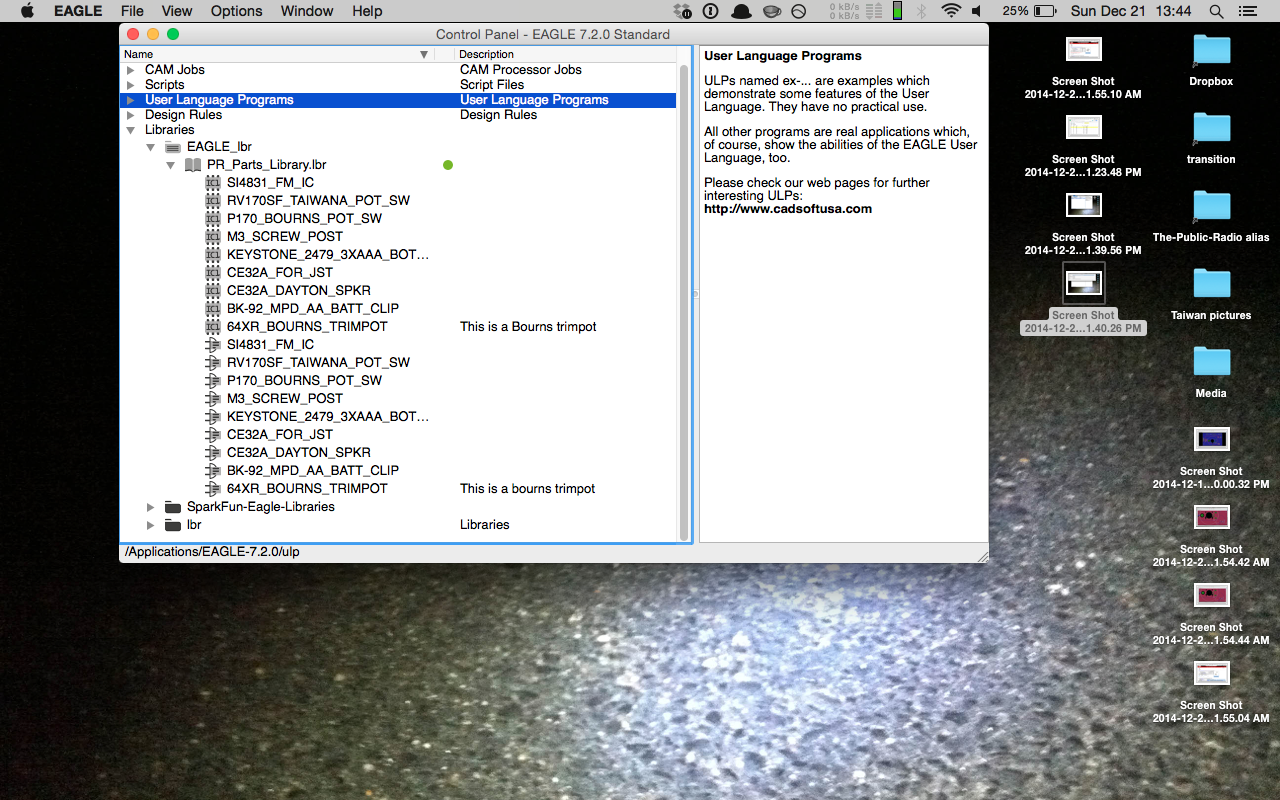

EAGLE Libraries on Github

This has been *such* a PITA, but I think I just got The Public Radio's EAGLE libraries onto Github in a way that makes sense.

The goal: To have everyone be able to access all of the parts that we use on The Public Radio, no matter where they are or who created the package/symbol/part, by just syncing the Github repo.

Our Github page now has one active repo (Embedded_Hardware) - and two for firmware & firmware libraries that are mostly inactive for now. Within Embedded_Hardware are two big subdirectories (EAGLE_CAD and EAGLE_lbr), plus an ARCHIVE and a place for us to put production files (Gerbers, etc).

Within EAGLE_lbr, there is one EAGLE CAD library file - PR_Parts_Library.lbr. From now on, that will be the default library for all packages, symbols, and parts that we create or modify for use in The Public Radio.

In order to make this all work, you need to add the local directory that you sync to Github to your EAGLE Libraries search path. I keep our Github repositories at ~/Documents/The-Public-Radio, so I added :$HOME/Documents/The-Public-Radio/Embedded_Hardware/EAGLE_lbr to the end of my Libraries search path:

And now the EAGLE libraries show up just fine!

Lastly, I opened up our .brd and .sch and went through all the parts I had created. I drew the speaker, potentiometer, antenna hole and batteries. The .brd and .sch included copies of those parts that came from a library on my local disc, so first I had to find those parts and copy them to our new shared library. Then I went into the .brd and .sch and swapped the old versions of those parts for the new ones.

Anyone else who's working on the project right now (that'd be Zach and Andy) can do the same with any of the footprints that they created. And anyone who's hoping to make their own (not sure why they would, but who am I to ask) can grab the entire Embedded_Hardware repository and modify packages to their heart's delight. If you do so and find a mistake we've made, please let me know - we're happy to take any pull requests that improve on our design!

Bunnie Huang

From a post called "Soylent Supply Chain:"

This point is often lost upon hardware startups. Very often I’m asked if it’s really necessary to go to Asia–why not just operate out of the US? Aren’t emails and conference calls good enough, or worst case, “can we hire an agent” who manages everything for us? I guess this is possible, but would you hire an agent to shop for dinner or buy clothes for you? The acquisition of material goods from markets is more than a matter of picking items from the shelf and putting them in a basket, even in developed countries with orderly markets and consumer protection laws. Judgment is required at all stages — when buying milk, perhaps you would sort through the bottles to pick the one with greatest shelf life, whereas an agent would simply grab the first bottle in sight. When buying clothes, you’ll check for fit, loose strings, and also observe other styles, trends, and discounted merchandise available on the shelf to optimize the value of your purchase. An agent operating on specific instructions will at best get you exactly what you want, but you’ll miss out better deals simply because you don’t know about them. At the end of the day, the freshness of milk or the fashion and fit of your clothes are minor details, but when producing at scale even the smallest detail is multiplied thousands, if not millions of times over.

More significant than the loss of operational intelligence, is the loss of a personal relationship with your supply chain when you surrender management to an agent or manage via emails and conference calls alone. To some extent, working with a factory is like being a houseguest. If you clean up after yourself, offer to help with the dishes, and fix things that are broken, you’ll always be welcome and receive better service the next time you stay. If you can get beyond the superficial rituals of politeness and create a deep and mutually beneficial relationship with your factory, the value to your business goes beyond money–intangibles such as punctuality, quality, and service are priceless.

This is really smart.

Directions in automation adoption

I've been spending a lot of time looking at industrial automation the past few days, and had an idle thought:

I've touched on this before, if only obliquely, when writing about MFG.com's role in manufacturing logistics. Much attention is being paid to companies who want to simplify (or circumvent) some part of the product development value chain. Many of these are companies I admire, and think are doing really valuable things. Take Within, whose 3D design software generates structures that are driven directly from functional constraints (but can't, as far as I can tell, deal well with thin-walled structures). Or Willow Garage's PR2, the really slick research robot (that takes charmingly long - 20 minutes per bath towel - to fold laundry).

Each of these is an incredibly impressive feat, and one that follows an ambitious (and I would argue honorable) line of thinking:

If we can encode all of the information needed to complete a routine yet complex task, then we can use machines to automate the process, freeing up our minds to do other (presumably more important) things.

But consider an alternate proposal:

If we can get machines to mimic a series of behaviors that humans can plan and execute with relative ease, then we can decrease the amount of rote mechanical work that humans need to do.

This is the tact taken seriously by Baxter, the admittedly not-too-serious (but cool nonetheless) humanoid task robot built by Rethink Robotics. Baxter learns by physically training his movements, presumably by the technician who he's "collaborating" with:

Even the traditional robotics companies, like Kuka, are moving in the direction of using robots simply to execute the complex tasks that humans calculate and perform with ease. Here a Kuka robot is trained how to clean a permanent mold by a BMW employee:

Both of these robots' use cases share a key feature: There's still a human doing the "hard" planning and calculation about how the task will be completed. In each case the robot doesn't understand the physical constraints or goals per se. Baxter has some awareness of his surroundings for sure, but all he knows is that his arms hit something; he doesn't have the vision or awareness of why that happened or how to correct for it.

Similarly, the Kuka bot doesn't understand that he's cleaning a mold, or have the facilities to learn how to do better work. He's just repeating a toolpath that he knows a human told him to do. Which, in this case, is good enough - and a hell of a lot faster than waiting for a computer vision expert to give him the intelligence required to do better.

I'm not sure what the implications of this are for the companies working to automate the design and supply chain. But the philosophical difference is striking, and I must say that the more hands-on model is very compelling - and I expect it to be so for the foreseeable future.

Parenthetically: All of the industrial 3D printing market is currently driven off of this same model: An intelligent, experienced technician makes manual edits to 3D CAD data in order to get a part to print within its design constraints. Anyone who suggests that build optimization is "right around the corner" is, in my opinion, *not* to be trusted. We're in a world of basic research still, and an automated design-print-post process chain is many years away.

Three interviews

I've done three interviews recently. The first, with Brian Barela, was on the future of work. It's in two parts:

The second was with New Hampshire Public Radio's "Word of Mouth," and was about The Public Radio's Kickstarter campaign:

The third was with Matthew Lesko, who you'd know as the question mark suit guy from late night infomercials - and who ends up being a really intelligent, thoughtful person. This one was also about The Public Radio:

Being interviewed is, IMO, *okay.* Holler if you want to chat :)

DMLS in process

This is my seatmast topper being printed from titanium 6/4 powder on an EOS M280 at DRT Medical - Morris.

This video clip is about 1-2mm into the build, so this is the very close to the bottom edge of the part (which, to be clear, is lying on its side). A lot of what's being printed during this clip is support structures & ribs that will help hold the part to the build plate, but you can clearly see the general shape of the part already.

This is 6th iteration on this build. In other words, we printed 5 parts before this one, and each of them failed for one reason or another. We've (and by we I mean mostly Dave Bartosik, the head Additive Technologist at DRT, with me trying to look over his shoulder) made a bunch of modifications to the build to help the part come out within spec, and I'm hoping that today we end up with something that has consistent inner diameters and is more or less useable.

Anyway, what you're seeing here is a 400 watt ytterbium fiber laser in the process of melting 30 micron layers of titanium powder. The recoating arm spreads a thin layer of powder, and then the laser scans a cross sectional slice of the part, and then the process repeats.

When the video goes into slow motion, notice the smoke that's coming off of the weld pool. The machine has a laminar flow of argon gas that's blown across the build platform (from top to bottom in this video) that pulls the soot away and filters it outside the machine.

More soon.