From Scott Miller's Hardware Workshop talk, which Zach attended yesterday (on behalf of The Public Radio).

I like this. I'm currently missing a *lot* of this stuff, and should work on improving that.

From Scott Miller's Hardware Workshop talk, which Zach attended yesterday (on behalf of The Public Radio).

I like this. I'm currently missing a *lot* of this stuff, and should work on improving that.

In a rush, I made these last night. One is a proper banner ad:

And the other is more boxy, for a display ad:

I'm kind of shocked that I modeled that jar, but it has ended up being *so* handy. These were not totally seamless to make (I went from Inventor .iam -> Inventor .ipn -> Inventor .idw -> export as .dwg -> AutoCAD -> export as .pdf -> Illustrator), but they could have been much worse.

The taglines & formatting were tough, and I'm still not totally convinced they're perfect... but for a few hours of after-work hacking, I think they came out pretty well.

From a CNET article about The Public Radio's Kickstarter (emphasis mine):

Public Radio is a hit, having raised over $72,000 with 14 days left to go. The original goal was a mere $25,000. For a fascinating breakdown of costs, pricing, economies of scale, uncertainties and triumphs for an electronics Kickstarter, check out Public Radio co-creator Spencer Wright's post on Medium. It should be required reading for anyone who aspires to launching a new crowdfunding project.

Nothing like a little ego boost on a Tuesday :)

The path to The Public Radio’s Kickstarter campaign, and how we see the challenges ahead.

About eighteen months ago, Zach came to me with an idea: an FM radio that only tunes to one station. We had recently completed MITx’s circuits & electronics course, and were looking for a project to apply ourselves to. This one was perfect: it was small, simple, and catchy. The Public Radio was born.

An early prototype.

Over the following year, we chipped away at the project on nights and weekends. It’s hard to say how much time was spent, but 400 hours each is conservative. We tracked expenses casually, but have records totaling about $5000, most of which went towards electronic parts, printed circuit boards, and prototype mechanical components. All in all, we invested the equivalent of tens of thousands of dollars on the project, and got a *ton* of value — in experience, mostly — out as a result. Regardless of where the project went, we both strongly felt that the trade was worth it.

In February, we launched a beta version of The Public Radio on Grand St. It was a great way for us to get a few units into the wild, and forced us to come up with scrappy solutions to the problems we’d face ahead. A lot of them weren’t permanent, but they were good enough — and getting support from random strangers felt great.

But building the radios was painstaking. We did all of the assembly in my kitchen in Bed Stuy, spending long nights hunkered over soldering irons to ship on time. It was tough, especially as — even ignoring our labor — we were barely covering our own costs.

Calculating our costs of goods sold is a bit tricky; different parts scale on totally different curves. A few notes:

Our first shipment of potentiometers.

The end result: In small quantities (<100) The Public Radio costs between $30 and $35, plus shipping and *not* including labor. Our price on Grand St. was $40 plus shipping, which we usually lost money on.

Inspecting the FM IC.

Labor is difficult to calculate precisely. Assembling surface mount components is time consuming; we spend about an hour per radio on that alone. Then there’s QC, mechanical assembly and tuning, all of which takes an additional 30–60 minutes. Add the fact that we were shipping orders one by one, and you’ve easily got two hours per radio in labor.

All in all, our Grand St launch did *not* make us money — but it did give us a great chance to cover some of our costs as we moved towards bigger volumes. For that, it was incredibly valuable; I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

Building electronic products by hand is hard. And expensive. So, scale it a bit.

Our ultimate goal is, and has been, to sell The Public Radio at wholesale prices direct to radio stations — who would use them as a tote bag replacement during fund drives. Remember that even if we scale our purchasing and assembly, these things need to be tuned to the customer’s station before they’re shipped. If we can tune them in batches — say, a hundred or a thousand all to the same station — then we save ourselves a *lot* of work.

Kickstarter is, admittedly, not specifically tailored to establishing a wholesale business. There are a lot of logistical challenges that we’ll face selling to individuals, and it’s unclear whether we can deal with them in a way that’s sustainable long-term. But Kickstarter allows us to get access to a big network of people, and gives an opportunity to reach out to station managers and say “we’re doing this thing; let’s talk about it.”

Figuring out the details of the campaign were *hard.* Aside from issues in producing a video (I can only blame this on the poor on-screen appearance of yours truly; both Zach and Colin (who was super gracious about helping us out) did a great job), the real difficulty was in setting the unit price (i.e.reward level) and funding goal.

We’re offering a handful of non-radio rewards in the campaign, but the bread and butter will be the “radio monogamists” level, which consists of an assembled and tuned Public Radio, including jar. Drawing from what we learned about buying habits on Grand St., we decided that $40 is a reasonable street price; we then averaged our shipping costs across the country and added $8 to cover those. As a result, the shipped price for our mainstay reward will be $48.

To be clear, the $40 baseline here is simply an estimate of what the market will bear. When we launched on Grand St, we started at $60, but after a week or so of no sales we dropped it to $40. That was the extent of our research, essentially — we couldn’t imagine it on a shelf for much more than $40, so $40 it is.

The funding goal was trickier. In the year+ that we’ve been working on this, we’ve spent $5–10k in cash — not to mention *months* of our weekends and after-work hours — developing it. It’s been a huge effort, and releasing it to the public will be even harder. But we’ll never get that time back, and anyway it has already paid for itself (in intangible rewards) many times over.

So, you just take that out of the equation — and expect to take many, many hours of future work out of the equation too.

We ended up setting a funding goal of $25,000, which corresponds to 500 units sold at $48, rounded up a thousand bucks for good luck. In the end, the deciding argument was this: while our cost structure at $25k probably wouldn’t make us money, the experience — and pulling it off — would be totally worth it.

The exact quantities at which our production modes shift are still up in the air, but there are a few ways we *think* this can go.

Obviously this didn’t happen, but nonetheless: At quantities of 500, we should be able to get our COGS down to about $30 (but not much lower). As a result, our income above COGS is about $10 per radio, though much of that will end up going towards payment processing & Kickstarter’s fee. Not counting costs incurred for reengineering (which would probably be minor, as the marginal benefits wouldn’t add up to much), supplier vetting, and our own labor, we’d expect net income for the whole project to be about $2500. In short, we’d lose money on the deal — but gain invaluable experience as a result.

In this scenario, we’re probably using a local vendor for our PCB assembly, and doing a lot of the mechanical assembly ourselves. There would be a *lot* of long nights ahead, and many of them would be spent doing assembly and distribution ourselves.

This is roughly where we are now — somewhere in the 1500 unit range — and it’s a *very* uncertain place to be. At 1500 units and a $28 COGS (we’d save a bit of money from the increased scale alone), our net income off of a $72,000 campaign will be in the range of $6500. If we reinvest that into engineering and reduce the COGS to $21 (still speculative at this point, but not without reason), we might be able to increase our net income to about $10,000. Do we take that risk? Either way, we’ll probably be incentivized to buy a number of our components in larger quantities; how do we deal with the excess inventory? Do we push The Public Radio to become a sustained business, even if we don’t currently have the demand to support it?

The Public Radio's final assembly step.

In this scenario, we’re probably outsourcing our PCB assembly to a larger shop and setting up a temporary space in NYC to do mechanical assembly, packaging, and distribution. Our roles become more managerial; we’ll get help to do a lot of the manual work. The career implications here loom large: this quantity will require a lot of energy, but might not provide full time employment for either of us.

Once we get to the 5,000–10,000 unit range, the game changes. At this point we’re outsourcing most of our operation, hiring a third party logistics company, and cutting out every fraction of a cent from our BOM. Production is probably done overseas, and the entire product is reengineered for scalability.

It’s conceivable, in this scenario, that we end up drawing salaries for our work. Regardless, we’re talking about *manufacturing* here — not just a project. I‘m not sure exactly what this would entail, but it’s safe to say that we probably wouldn’t be shipping radios out of my apartment.

There were a few days, early in our campaign, when we weren’t sure if we’d make $25k. As I write this, we’re at $70k with two weeks left, and we’ve had interest from both radio stations and retailers for large-quantity orders.

In short, we’re moving towards something resembling a sustainable business — which, to be honest, is a bit surprising. Many are the times that we’ve told ourselves that what we were working on was good in and of itself; to have it get bigger — and offer opportunities to think about a larger scale of commerce — is exciting and weird.

Regardless, the path forward is fascinating. We’ve stumbled upon a niche product that people seem to really want, and now we have the chance — and the priveledge — to fulfill that desire. Whatever the future holds, we’re ready for it — and look forward to sharing what we learn.

The Public Radio's Kickstarter raised upwards of $30k last night, and my inbox is *crazy.* Here's one response I wrote:

Thanks for your note, and the compliments. You bring up some serious (and warranted, I think) questions, and while I probably can't fully answer them (my inbox is going a little crazy), I did want to respond quickly.

First: We don't have a business plan per se, and I tend to think that's a *good* thing. There were a few possible outcomes of the campaign (fund at $25k, where we make them all by hand, or fund at an order of magnitude higher, where we need to scale and outsource production & logistics), and it was impossible to plan for them ahead of time. That said, we spent a *lot* of time going through those scenarios and feel confident (a bit surprised, but confident nonetheless) that we're well equipped to handle what comes.

Second: The Public Radio's design is whimsical, but our intentions are not. While the challenges we'll face moving forward are different than those we've managed previously, we're both serious, professional adults, and each of us has managed large scale projects (which carried bigger risks than The Public Radio does) in our careers. In short: We're are not taking our responsibilities here lightly.

Third: Price. This is fuzzier, but the bottom line is that we live in a free (ish) market, and The Public Radio is priced at what we thought the market would bear. Keep in mind, also, that electronic devices are *really* expensive to make in low quantities (anything less than 10,000 annually, with annual commitments and long lead times). The Public Radio will *not* make us rich, but we were sure to set the funding and reward levels such that we wouldn't go bankrupt, either.

All of that aside, we do appreciate your feedback - we've been working on this for a year and a half now, and it's great to hear that what we're doing is resonating in some way. Hopefully I answered some of your questions; if not, please let me know and I'll try to clear it up :)

Spencer

The Public Radio is coming along. Photos from the field:

The Public Radio has moved a little slowly over the past few months. Zach has been busy, and I've got too much on my plate, and scheduling has been tricky. But we *have* made progress, and I'm here to tell you about it.

After the last hardware round, we spent an hour and developed a feature wishlist. It included:

All of these (plus a few more technical ones - see our GitHub repository for the current designs) have been completed. A few stragglers have yet to be implemented:

I like the way the new design looks. Eagle is *not* my favorite piece of design software, but board layout is fun - and I'm really proud of our current design.

On Sunday evening, we ordered a batch of 10 of these from Advanced Circuits. Advanced is expensive, but they turn the parts around quickly; ours should ship today. Meanwhile, our custom antennas departed (two or three weeks late, but whatever) Hong Kong yesterday. With any luck, the antennas will show up within a day or two of the boards - giving us time to assemble a few PCBs and then quickly put the radios into service.

In the meantime, Zach hacked an awesome way to tune the radios using an Arduino. It should save us a lot of time, and will be *key* when we're shipping these things across the country.

So. Movement. Happening.

I find this to be an endless opportunity for iteration and refinement. It can always be shorter, quicker, closer together.

More Public Radio updates tomorrow, or check the GitHub repo here.

This is what an order of 1000 Taiwanese potentiometers looks like:

These are for the upcoming production run of The Public Radio. We're probably doing a design revision on the boards in the next week, and will be assembling a small batch in-house before we send the rest out to a PCB assembly house.

FYI, these are a non-stock part from Taiwan Alpha Electronics. They were very easy to deal with and shipped (on time) for delivery in Brooklyn just 32 business days after payment.

There's more on our potentiometer requirements in an older post, here.

In prep for my lil' essay on McMaster-Carr, I went through and updated the parts list for The Public Radio. Note here how a number of the parts (the ones with the 9-digit alphanumeric McMaster-Carr part numbers) have incomplete/inaccurate part data - and moreover, don't include hyperlinks to the McMaster product page, etc.

Also note: How much I like this drawing :)

PCBA, recently @ The Public Radio:

We've got about a dozen beta radios out in the wild right now, and are working on an additional 10 or so. There are a few small hardware revisions that are yet to be made, but the overall design is about right, and we'll be rolling out a larger launch in the coming months. Stay tuned.

Product photography is fun, and weird.

Today I spent the majority of my day on-location shooting The Public Radio with Zach and Colin (and with help from Hannah, Lianna and Chris). It was good, and exhausting, and fun.

When I was building bikes, I self-consciously photographed a huge portion of my life. My aim was presumably to build a personal brand that would improve the appeal of my company, but looking back I wonder how much of it was pure narcissism.

Now it's (ostensibly) different; I'm part of a larger team, and in many ways the aesthetic that we're selling is distinct from my own. Sure, I use Mason jars, and I truly enjoy FM from time to time - and when I do, I only listen to one station. But the challenges that interest me about The Public Radio are largely distinct from the reasons that (I believe) our customers would buy it, and that has a huge effect on the way I present it to the world. It frees me up, and removes self-consciousness from the equation. It makes it much easier.

Anyway. Consider The Public Radio's crowdfunding campaign begun. Stay in touch for updates.

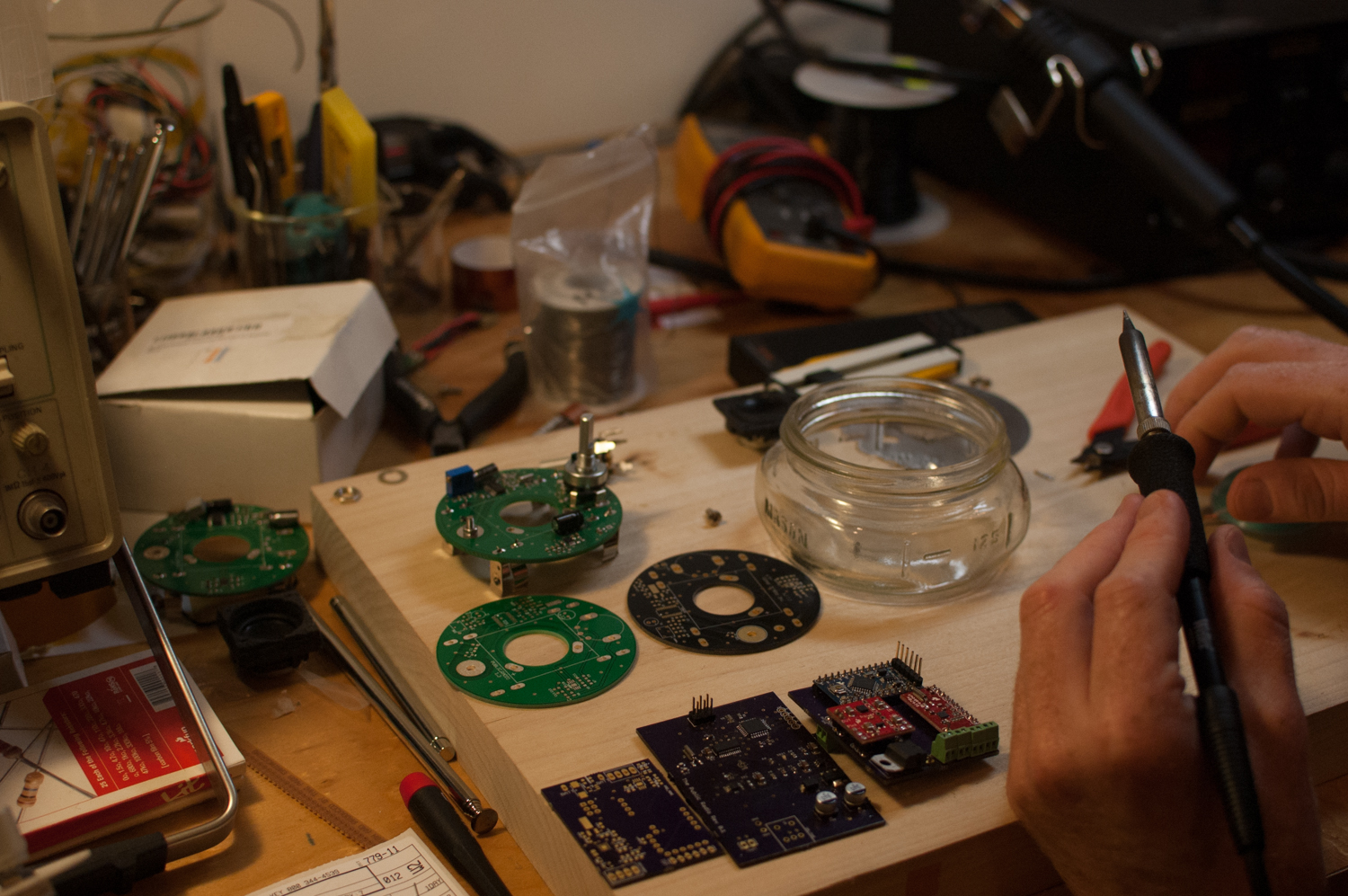

Yesterday I received new PCBs for The Public Radio, and quickly built up a few units.

These will go out to beta testers early next week.

Building them up has been really fun - they work well, and all of the parts are organized in a way that makes assembly pretty straightforward. Getting everything all knolled nicely actually helps a significant amount in PCB assembly - now, if I can just get my parts organizer up and running...

New PCBs for The Public Radio should arrive in ~2 weeks. Only a few changes, but will be much easier to assemble + will have pretty graphics on the bottom.

Thanks again to Jonathan Bobrow for everything that's cool about our current logo :)

Have been a little hectic.

In addition to trying to make some long overdue progress on my DMLS work, The Public Radio is kind of heating up right now. We received a new batch of PCBs, and got a few of them built up quickly.

To our astonishment, the first board we built worked immediately. This was actually kind of weird - we were expecting at least a bridge or two would need to be fixed, and there was always the chance that we had made a design error. Having our first board turn right on, and then quickly tune to WBGO 88.3, was a real kick.

Things won't always go so well, though, and so the following day we spent a bit of time straightening the workshop and setting up a bit of new tooling. The Public Radio HQ is now the home to a brand-old 1984 Tektronix 2465, a 4-channel 300MHz analog scope. We also picked up an inexpensive hot air rework station, and I dumped some bike parts out of one of my small parts cabinets and dragged it in to the city as well.

We don't have stencils for these boards (aligning circular stencils requires a bit more foresight than we could muster when we made the purchase) so we're laying out solder paste by hand with a syringe and toothpicks. Then we laid out a big piece of card stock and placed SMT components out part by part and set out with tweezers and loupes to place them on boards.

Our boards have two fine-pitch parts on them (the FM IC and the amplifier), and then they're almost all 0603 packages. These are manageable once you get going, but initially they're just fucking small. Anything smaller and we'd have a really hard time hand assembling these boards.

There are a few small modifications that we'll make before we go into production. Our thru hole trimpot's package needs to be changed, and we need to do a little tweaking on the gain setting resistors going into the amplifier, and I want to spend a little while getting graphics on the silkscreen layers. But these are minor changes; overall, the boards are 95% there.

On Monday we'll be receiving a batch of lasercut stainless steel lids, and we'll finally see how our whole assembly fits together IRL.

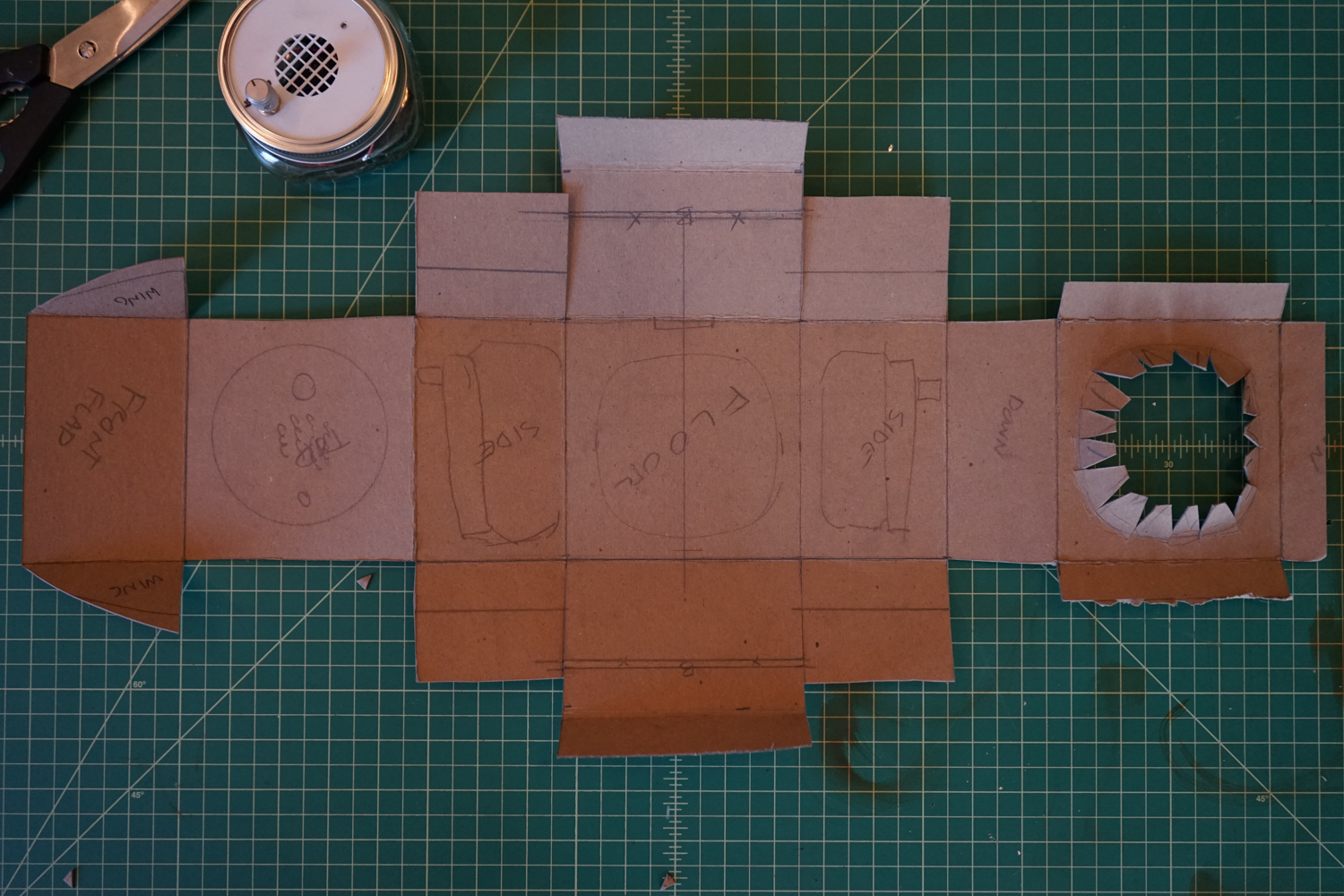

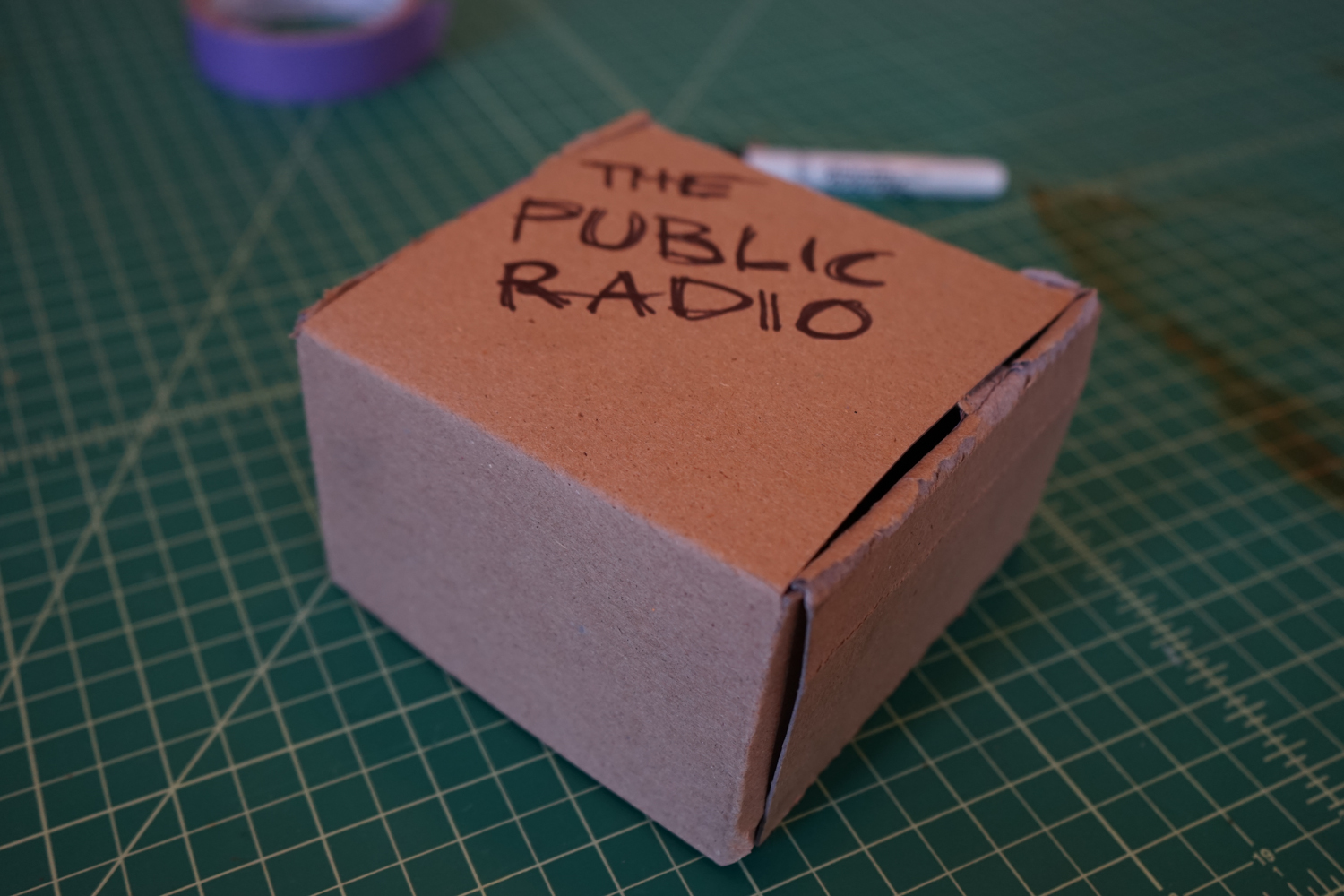

Spent about an hour and a half on The Public Radio's box today. It's just a quick prototype, but it should help out when we start to look at production costs.

Fun :)

The Public Radio's PCBs shipped today. They're scheduled to be delivered on Monday.

That's Hangzhou to NY in 1 business day.

How does this work?