From Scott Miller's Hardware Workshop talk, which Zach attended yesterday (on behalf of The Public Radio).

I like this. I'm currently missing a *lot* of this stuff, and should work on improving that.

From Scott Miller's Hardware Workshop talk, which Zach attended yesterday (on behalf of The Public Radio).

I like this. I'm currently missing a *lot* of this stuff, and should work on improving that.

Cardboard boxes being made outside Taichung, Taiwan. A serious hat-tip to Kane and Adam at Brilliant Bicycles for taking me here. More reports soon :)

I got engaged! So, here's a gif.

Crazy, right?

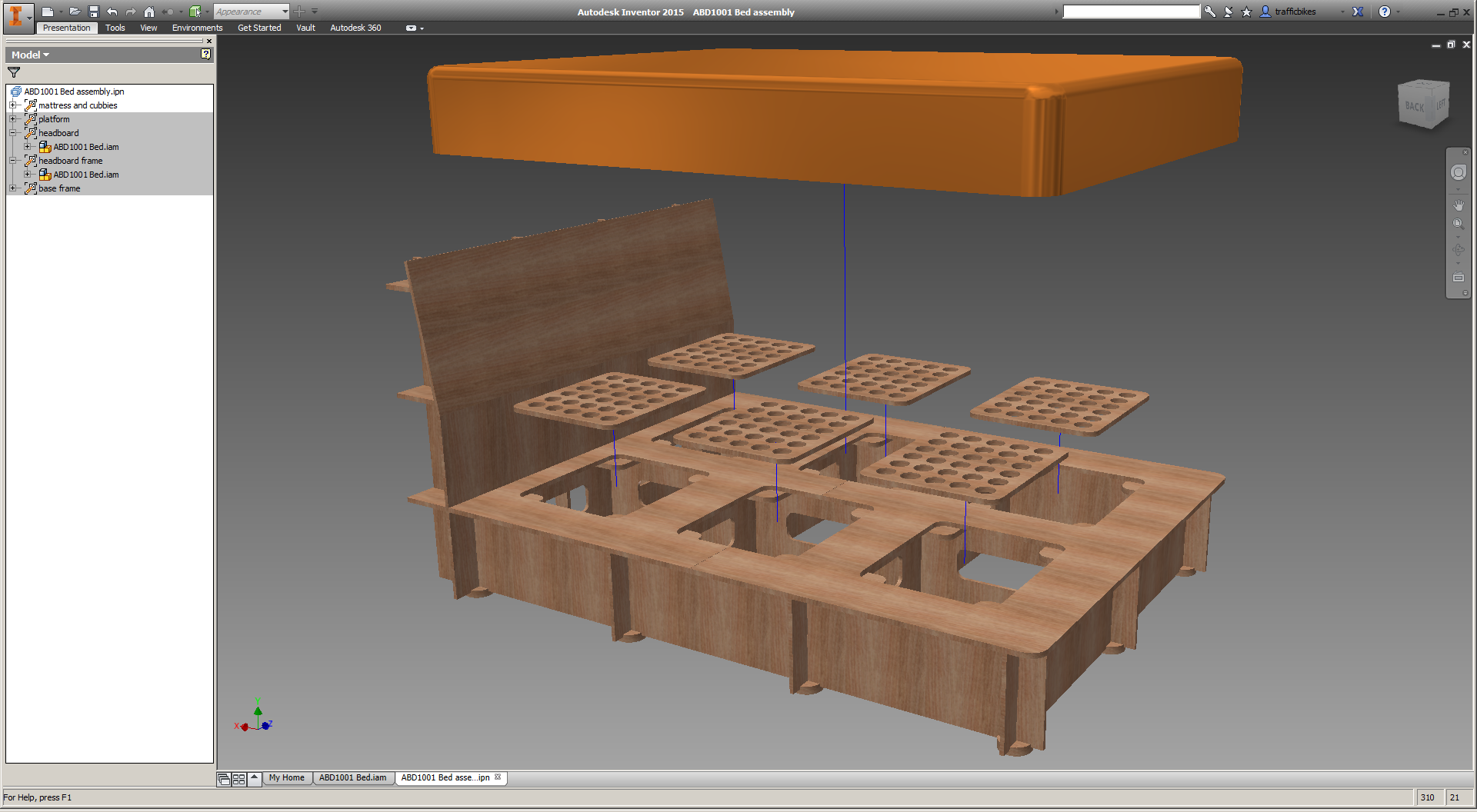

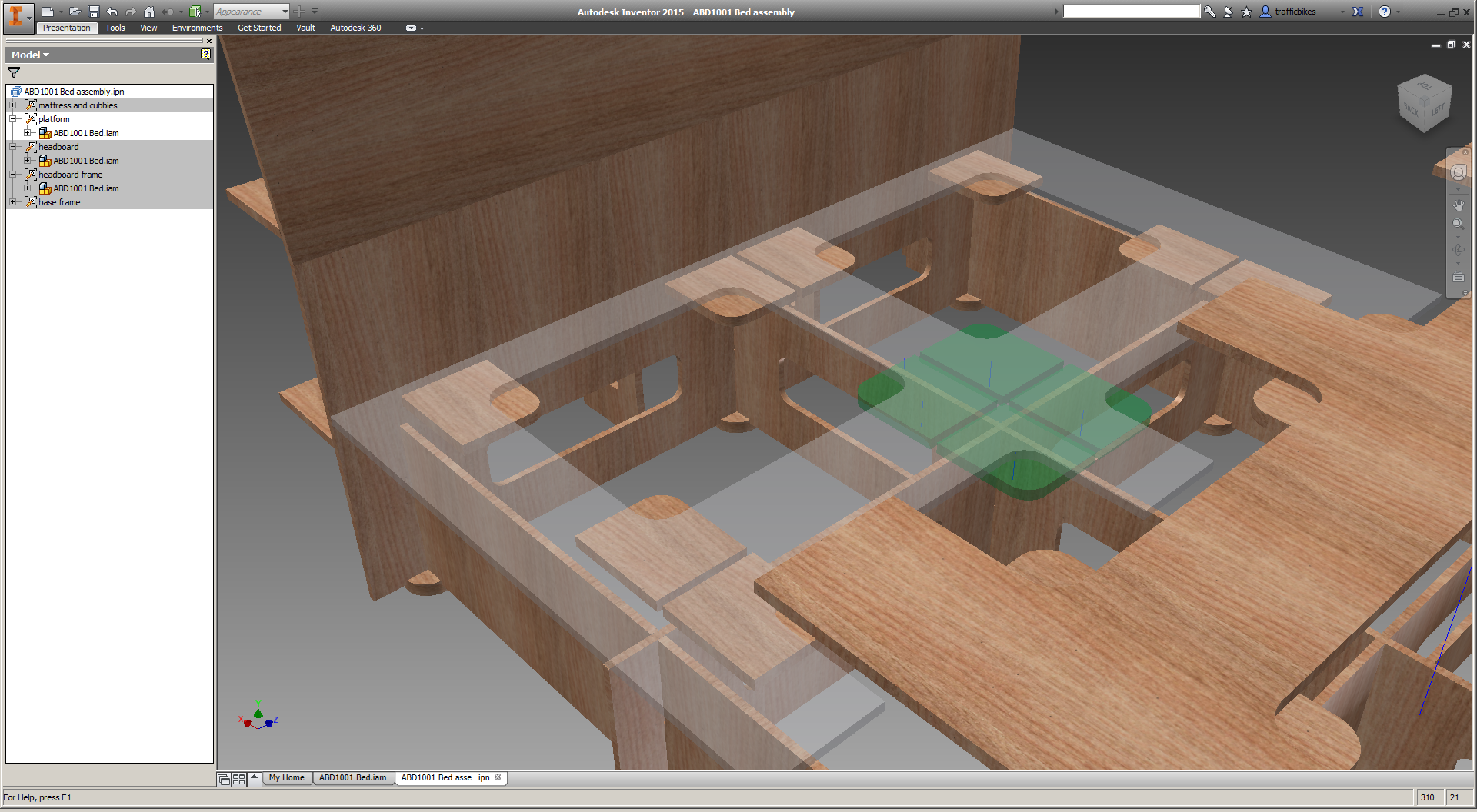

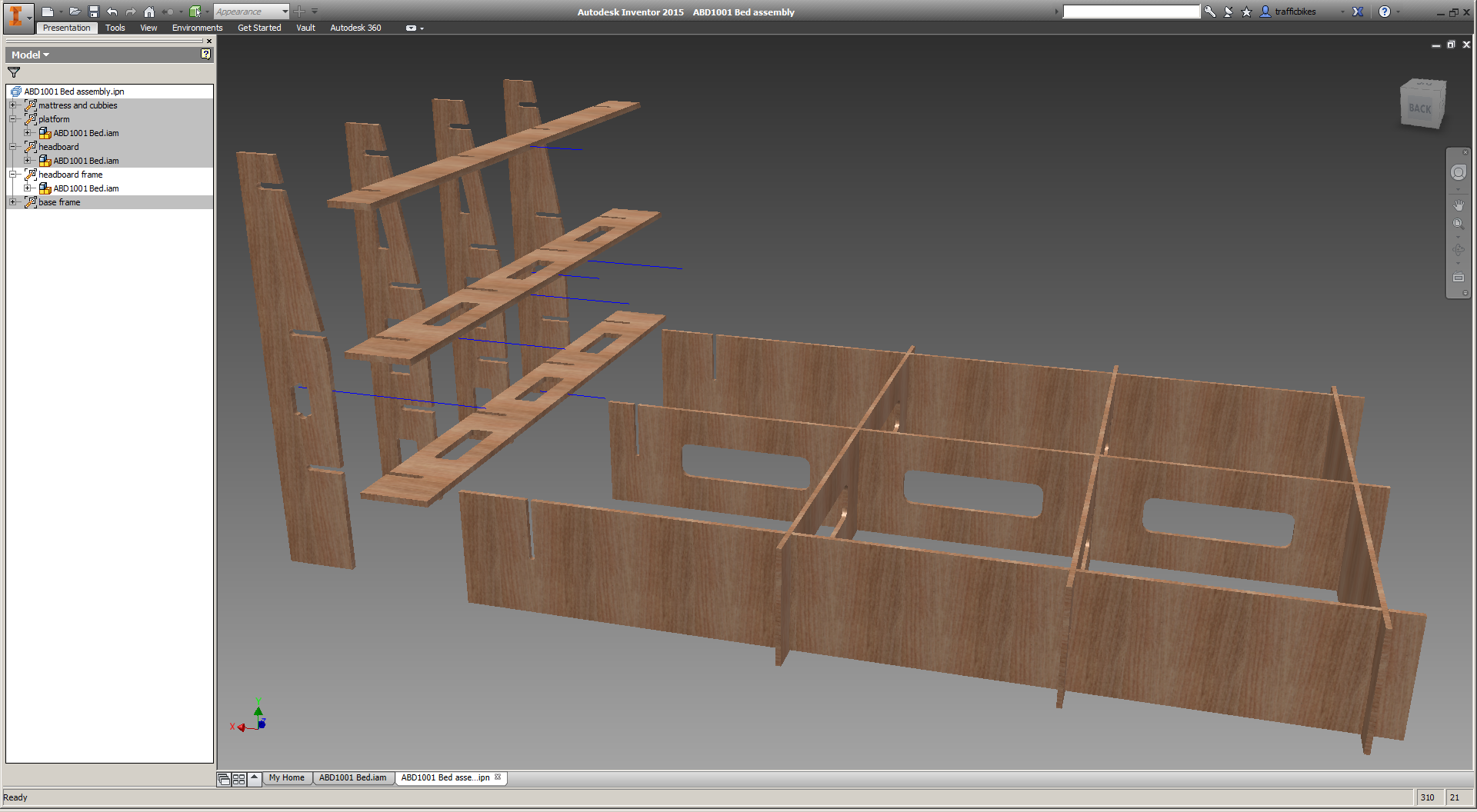

Today a bunch of walnut plywood was delivered to Old World Mouldings, and Paul started cutting them almost immediately.

Router toolpaths, courtesy Paul.

The first few parts are cut.

I'm currently feeling a tad bit nervous that my design is off in some way, but there's not a ton I can do about it until all of the parts are ready - which should be late this week. I did find a pretty big error midday yesterday - I had assumed that 5/8" walnut would be available, and it's not - and was able to correct it before production started. In the process, I went through as many of the details as I could think up, and I *think* everything is okay.

Short-run manufacturing is tough. If I were being really careful, I'd ask them to run all the parts for one bed first, and I'd test it to confirm it works as I want it to. But it's a bit of a trip to get there, and running three copies of the same part all at once is a lot easier for them. I still may try to do a mid-project mockup, but it'll be a bit of a trick to work it out.

From "A supposedly fun thing I'll never do again."

Death and Conroy notwithstanding, we're maybe now in a position to appreciate the lie at the dark heart of Celebrity's brochure. For this - the promise to sate the part of me that always and only WANTS - is the central fantasy that the brochure is selling. The thing to notice is that the real fantasy here isn't that this promise will be kept, but that such a promise is keepable at all. This is a big one, this lie.* And of course I want to believe it - fuck the Buddha - I want to believe that maybe this Ultimate Fantasy Vacation will be enough pampering, and this time the luxury and pleasure will be so completely and faultlessly administered that my Infantile part will be sated.**

*It may well be the Big One, come to think of it.

**The fantasy they're selling is the whole reason why all the subjects in all the brochures' photos have facial expressions that are at once orgasmic and oddly slack: these expressions are the facial equivalent of going "Aaaahhhhh," and the sound is not just that of somebody's Infantile part exulting in finally getting the total pampering it's always wanted but also that of the relief all the other parts of that person feel when the Infantile part finally shuts up.

Me, brainstorming, last week:

I want to create new value by applying my own critical thinking and creativity to compelling and challenging problems, especially in cases that allow me to collaborate with excited, intelligent people.

I really enjoy Alexis Madrigal's writing, and 5 Intriguing Things is the *best.* He just left the Atlantic for Fusion (joining another of my favorites, Felix Salmon), and his note in today's newsletter struck a chord with me. Emphasis mine:

My animating belief is that politicians and bullshitters and ideologues have taken the idea of societal change and replaced it with a particular notion of technology as the only or main causal mechanism in history. Somehow, we’ve been convinced that only machines and corporations make the future, not people and ideas. And that's not true. Just take a look back in history at the mid-century “futurists” projecting they’d be living on Mars with their stay-at-home wives, playing pinochle in all-white communities.

This is not to denigrate the importance of technology out there in the world or call for a return to pre-industrial or pre-Internet society. Because all the other types of change are being mediated by our phones and networks, artificial intelligences and robots. And those dynamics are really important.

But if you really want to know what the future is going to be like, you can't just talk about the billions of phones in China or paste some logarithmic growth charts into your Powerpoint. You have to go to the places where people are experiencing bits of the future—living the changes—and use that reporting to weave together a multivalent portrait of our possible futures. You have to get the many ways of thinking about the future into the same space, so you can see how they fit together.

I like this.

In a rush, I made these last night. One is a proper banner ad:

And the other is more boxy, for a display ad:

I'm kind of shocked that I modeled that jar, but it has ended up being *so* handy. These were not totally seamless to make (I went from Inventor .iam -> Inventor .ipn -> Inventor .idw -> export as .dwg -> AutoCAD -> export as .pdf -> Illustrator), but they could have been much worse.

The taglines & formatting were tough, and I'm still not totally convinced they're perfect... but for a few hours of after-work hacking, I think they came out pretty well.

From a CNET article about The Public Radio's Kickstarter (emphasis mine):

Public Radio is a hit, having raised over $72,000 with 14 days left to go. The original goal was a mere $25,000. For a fascinating breakdown of costs, pricing, economies of scale, uncertainties and triumphs for an electronics Kickstarter, check out Public Radio co-creator Spencer Wright's post on Medium. It should be required reading for anyone who aspires to launching a new crowdfunding project.

Nothing like a little ego boost on a Tuesday :)

The path to The Public Radio’s Kickstarter campaign, and how we see the challenges ahead.

About eighteen months ago, Zach came to me with an idea: an FM radio that only tunes to one station. We had recently completed MITx’s circuits & electronics course, and were looking for a project to apply ourselves to. This one was perfect: it was small, simple, and catchy. The Public Radio was born.

An early prototype.

Over the following year, we chipped away at the project on nights and weekends. It’s hard to say how much time was spent, but 400 hours each is conservative. We tracked expenses casually, but have records totaling about $5000, most of which went towards electronic parts, printed circuit boards, and prototype mechanical components. All in all, we invested the equivalent of tens of thousands of dollars on the project, and got a *ton* of value — in experience, mostly — out as a result. Regardless of where the project went, we both strongly felt that the trade was worth it.

In February, we launched a beta version of The Public Radio on Grand St. It was a great way for us to get a few units into the wild, and forced us to come up with scrappy solutions to the problems we’d face ahead. A lot of them weren’t permanent, but they were good enough — and getting support from random strangers felt great.

But building the radios was painstaking. We did all of the assembly in my kitchen in Bed Stuy, spending long nights hunkered over soldering irons to ship on time. It was tough, especially as — even ignoring our labor — we were barely covering our own costs.

Calculating our costs of goods sold is a bit tricky; different parts scale on totally different curves. A few notes:

Our first shipment of potentiometers.

The end result: In small quantities (<100) The Public Radio costs between $30 and $35, plus shipping and *not* including labor. Our price on Grand St. was $40 plus shipping, which we usually lost money on.

Inspecting the FM IC.

Labor is difficult to calculate precisely. Assembling surface mount components is time consuming; we spend about an hour per radio on that alone. Then there’s QC, mechanical assembly and tuning, all of which takes an additional 30–60 minutes. Add the fact that we were shipping orders one by one, and you’ve easily got two hours per radio in labor.

All in all, our Grand St launch did *not* make us money — but it did give us a great chance to cover some of our costs as we moved towards bigger volumes. For that, it was incredibly valuable; I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

Building electronic products by hand is hard. And expensive. So, scale it a bit.

Our ultimate goal is, and has been, to sell The Public Radio at wholesale prices direct to radio stations — who would use them as a tote bag replacement during fund drives. Remember that even if we scale our purchasing and assembly, these things need to be tuned to the customer’s station before they’re shipped. If we can tune them in batches — say, a hundred or a thousand all to the same station — then we save ourselves a *lot* of work.

Kickstarter is, admittedly, not specifically tailored to establishing a wholesale business. There are a lot of logistical challenges that we’ll face selling to individuals, and it’s unclear whether we can deal with them in a way that’s sustainable long-term. But Kickstarter allows us to get access to a big network of people, and gives an opportunity to reach out to station managers and say “we’re doing this thing; let’s talk about it.”

Figuring out the details of the campaign were *hard.* Aside from issues in producing a video (I can only blame this on the poor on-screen appearance of yours truly; both Zach and Colin (who was super gracious about helping us out) did a great job), the real difficulty was in setting the unit price (i.e.reward level) and funding goal.

We’re offering a handful of non-radio rewards in the campaign, but the bread and butter will be the “radio monogamists” level, which consists of an assembled and tuned Public Radio, including jar. Drawing from what we learned about buying habits on Grand St., we decided that $40 is a reasonable street price; we then averaged our shipping costs across the country and added $8 to cover those. As a result, the shipped price for our mainstay reward will be $48.

To be clear, the $40 baseline here is simply an estimate of what the market will bear. When we launched on Grand St, we started at $60, but after a week or so of no sales we dropped it to $40. That was the extent of our research, essentially — we couldn’t imagine it on a shelf for much more than $40, so $40 it is.

The funding goal was trickier. In the year+ that we’ve been working on this, we’ve spent $5–10k in cash — not to mention *months* of our weekends and after-work hours — developing it. It’s been a huge effort, and releasing it to the public will be even harder. But we’ll never get that time back, and anyway it has already paid for itself (in intangible rewards) many times over.

So, you just take that out of the equation — and expect to take many, many hours of future work out of the equation too.

We ended up setting a funding goal of $25,000, which corresponds to 500 units sold at $48, rounded up a thousand bucks for good luck. In the end, the deciding argument was this: while our cost structure at $25k probably wouldn’t make us money, the experience — and pulling it off — would be totally worth it.

The exact quantities at which our production modes shift are still up in the air, but there are a few ways we *think* this can go.

Obviously this didn’t happen, but nonetheless: At quantities of 500, we should be able to get our COGS down to about $30 (but not much lower). As a result, our income above COGS is about $10 per radio, though much of that will end up going towards payment processing & Kickstarter’s fee. Not counting costs incurred for reengineering (which would probably be minor, as the marginal benefits wouldn’t add up to much), supplier vetting, and our own labor, we’d expect net income for the whole project to be about $2500. In short, we’d lose money on the deal — but gain invaluable experience as a result.

In this scenario, we’re probably using a local vendor for our PCB assembly, and doing a lot of the mechanical assembly ourselves. There would be a *lot* of long nights ahead, and many of them would be spent doing assembly and distribution ourselves.

This is roughly where we are now — somewhere in the 1500 unit range — and it’s a *very* uncertain place to be. At 1500 units and a $28 COGS (we’d save a bit of money from the increased scale alone), our net income off of a $72,000 campaign will be in the range of $6500. If we reinvest that into engineering and reduce the COGS to $21 (still speculative at this point, but not without reason), we might be able to increase our net income to about $10,000. Do we take that risk? Either way, we’ll probably be incentivized to buy a number of our components in larger quantities; how do we deal with the excess inventory? Do we push The Public Radio to become a sustained business, even if we don’t currently have the demand to support it?

The Public Radio's final assembly step.

In this scenario, we’re probably outsourcing our PCB assembly to a larger shop and setting up a temporary space in NYC to do mechanical assembly, packaging, and distribution. Our roles become more managerial; we’ll get help to do a lot of the manual work. The career implications here loom large: this quantity will require a lot of energy, but might not provide full time employment for either of us.

Once we get to the 5,000–10,000 unit range, the game changes. At this point we’re outsourcing most of our operation, hiring a third party logistics company, and cutting out every fraction of a cent from our BOM. Production is probably done overseas, and the entire product is reengineered for scalability.

It’s conceivable, in this scenario, that we end up drawing salaries for our work. Regardless, we’re talking about *manufacturing* here — not just a project. I‘m not sure exactly what this would entail, but it’s safe to say that we probably wouldn’t be shipping radios out of my apartment.

There were a few days, early in our campaign, when we weren’t sure if we’d make $25k. As I write this, we’re at $70k with two weeks left, and we’ve had interest from both radio stations and retailers for large-quantity orders.

In short, we’re moving towards something resembling a sustainable business — which, to be honest, is a bit surprising. Many are the times that we’ve told ourselves that what we were working on was good in and of itself; to have it get bigger — and offer opportunities to think about a larger scale of commerce — is exciting and weird.

Regardless, the path forward is fascinating. We’ve stumbled upon a niche product that people seem to really want, and now we have the chance — and the priveledge — to fulfill that desire. Whatever the future holds, we’re ready for it — and look forward to sharing what we learn.

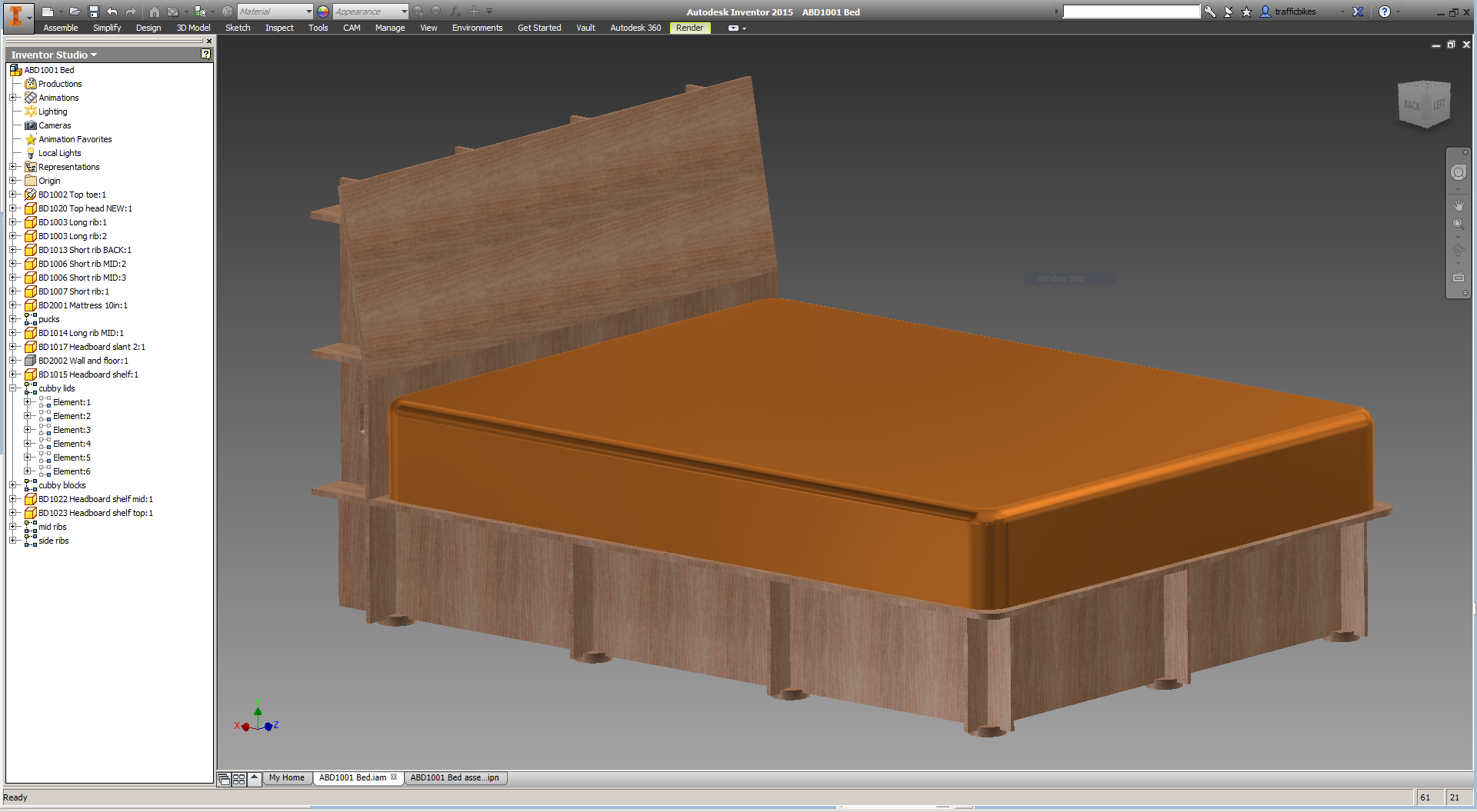

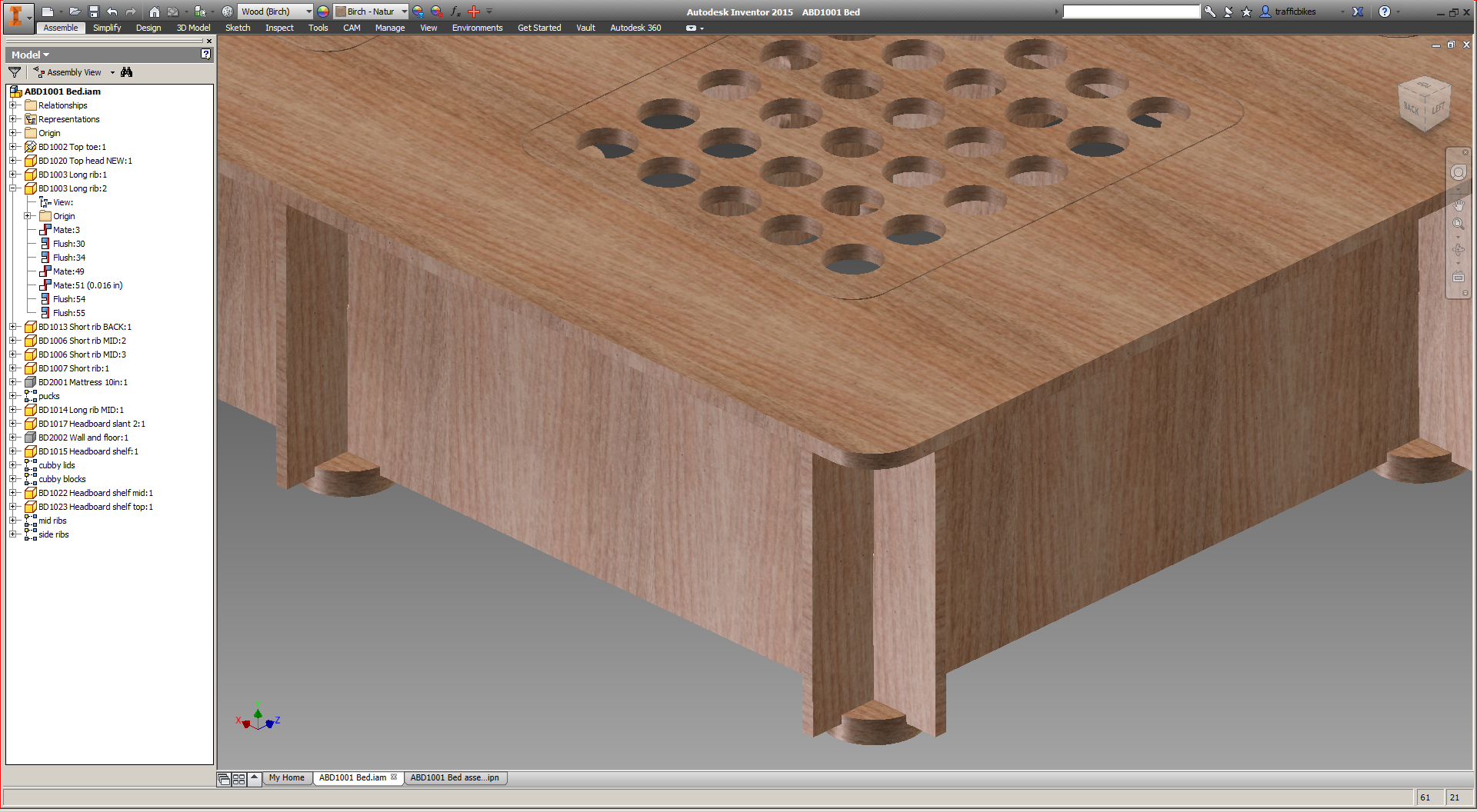

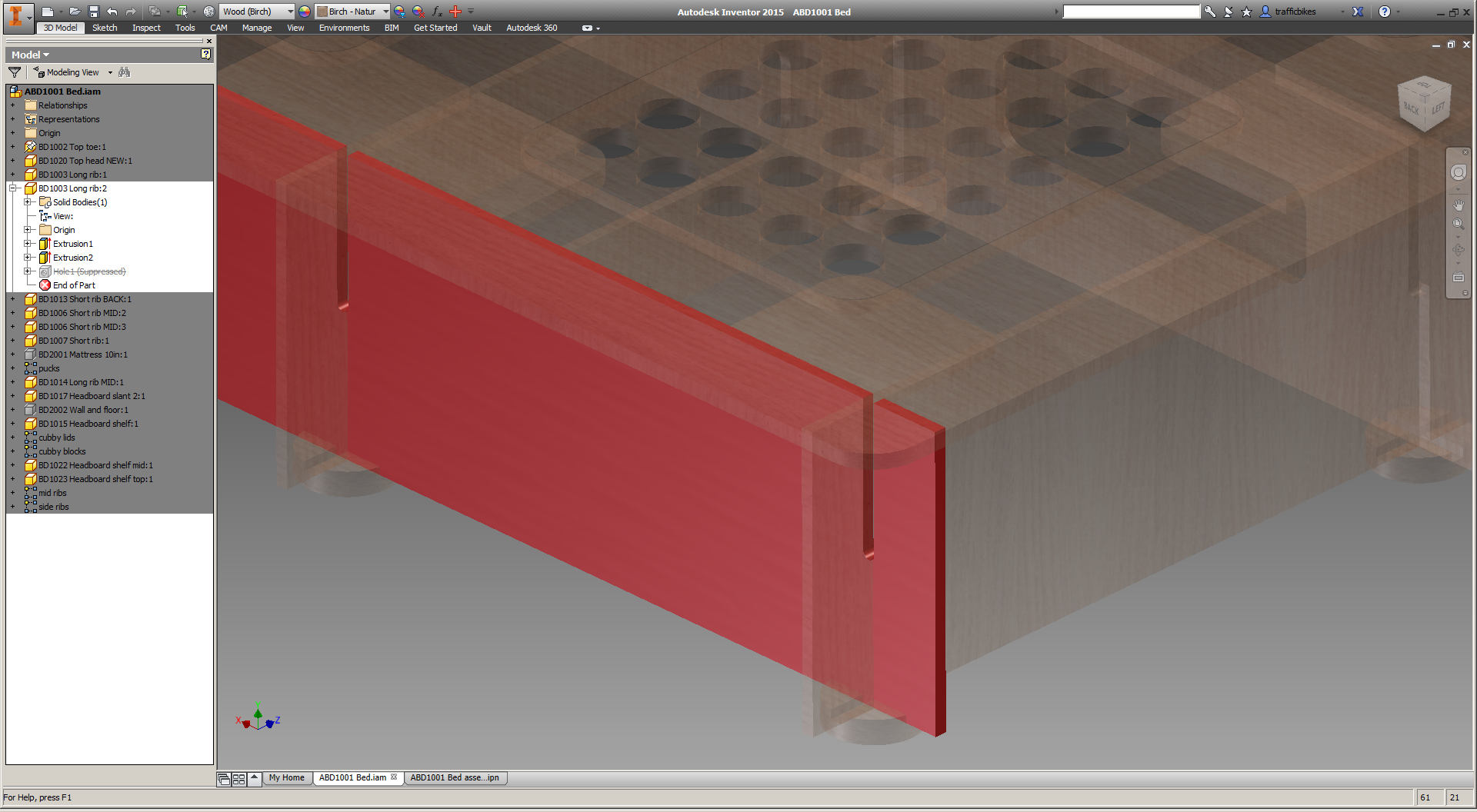

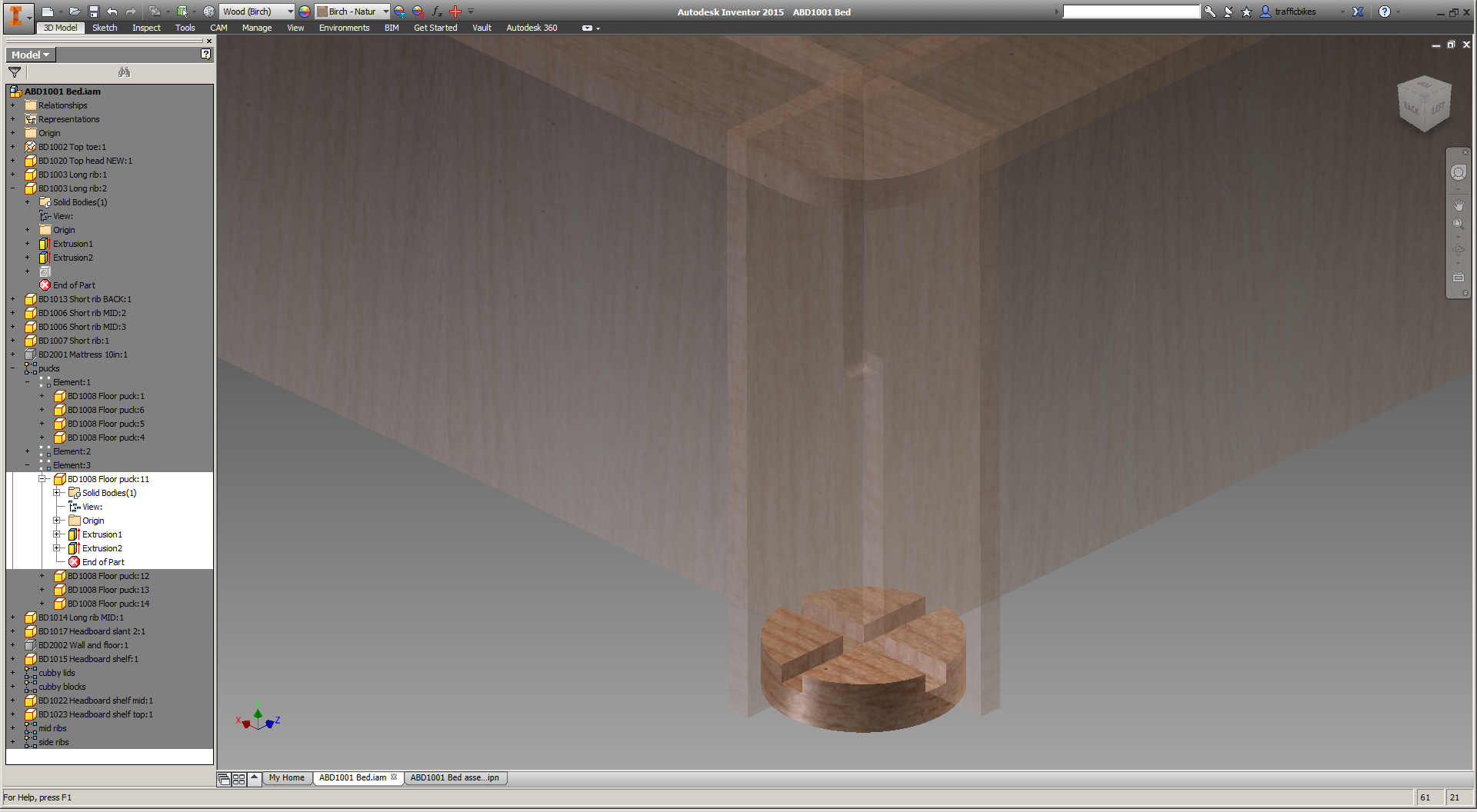

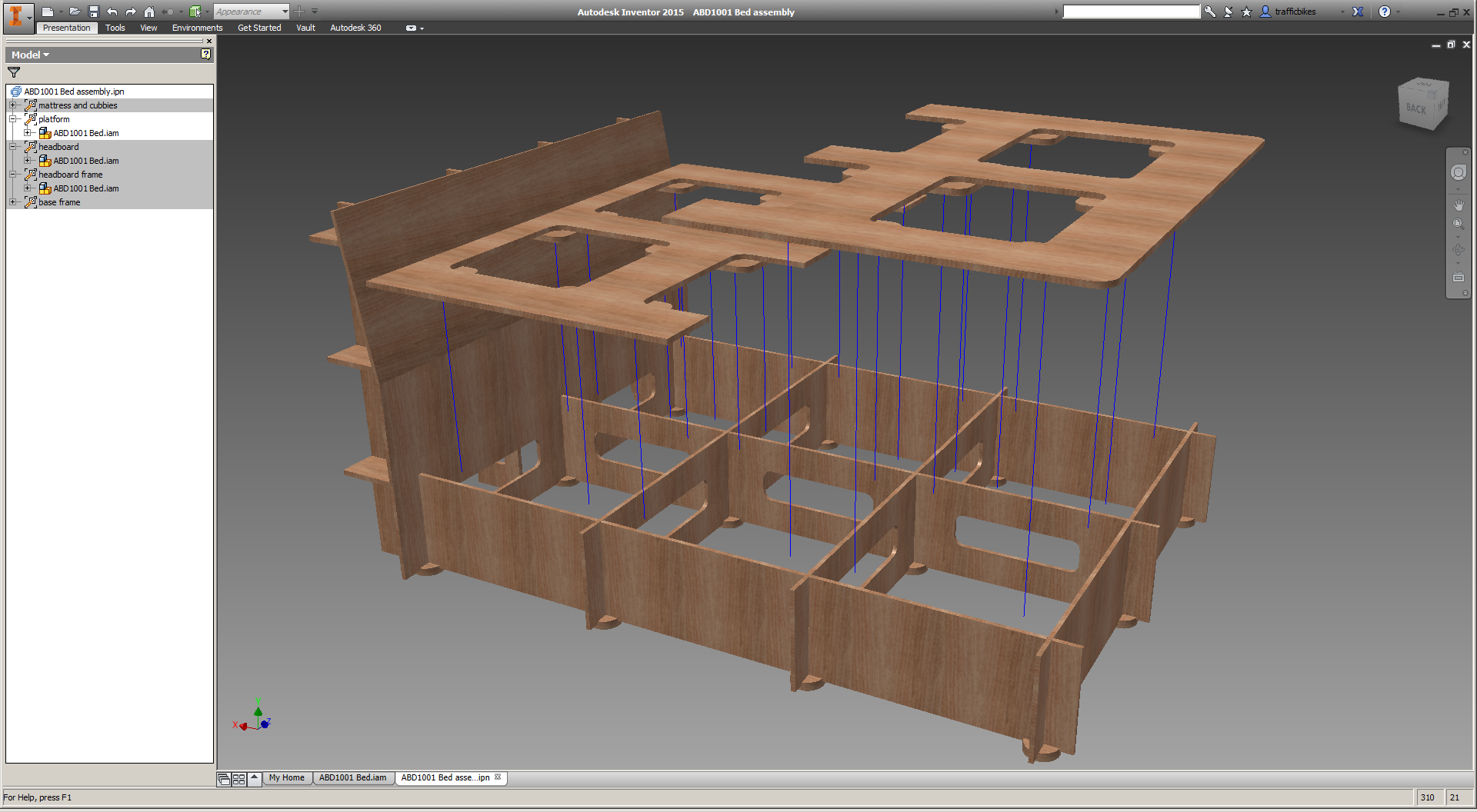

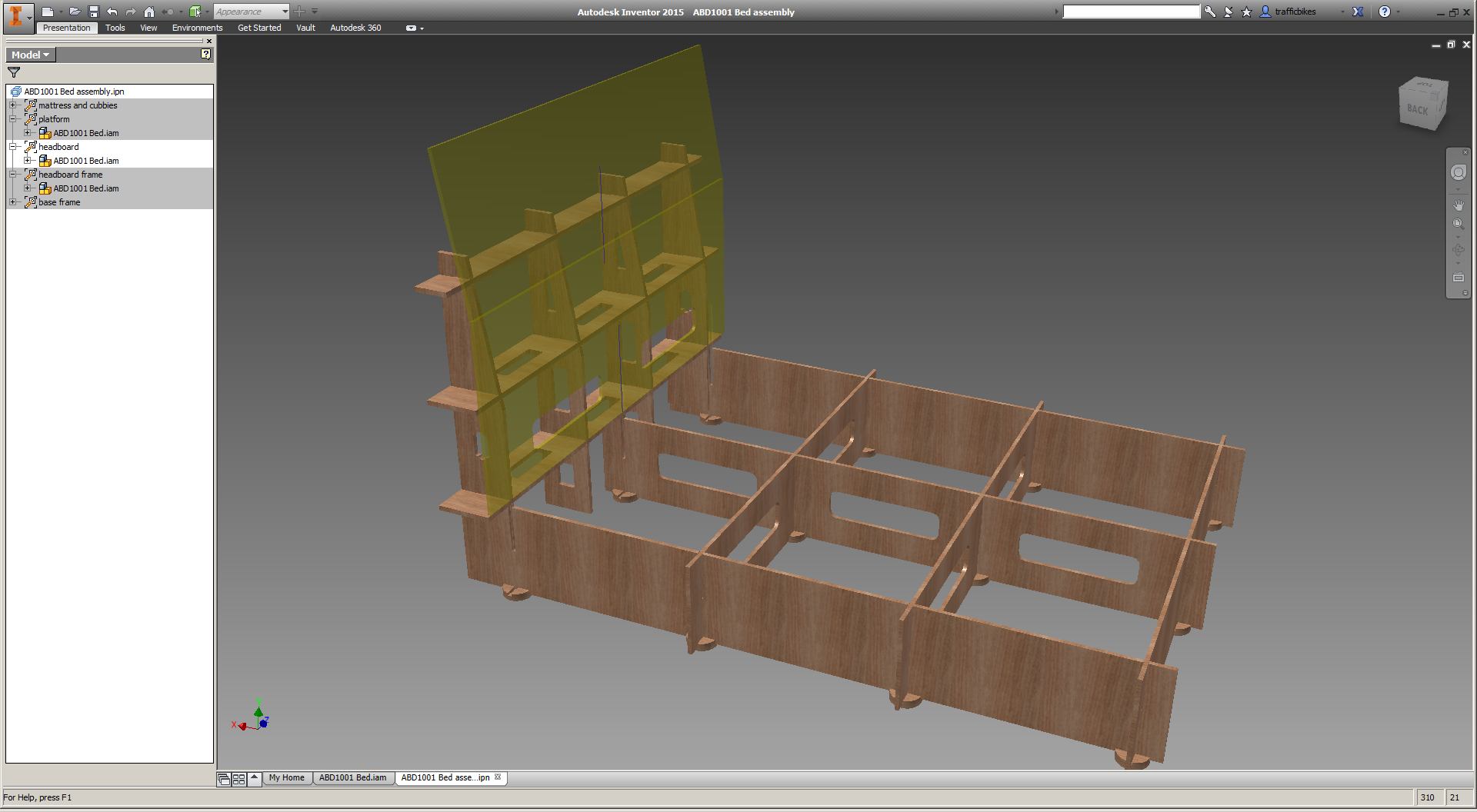

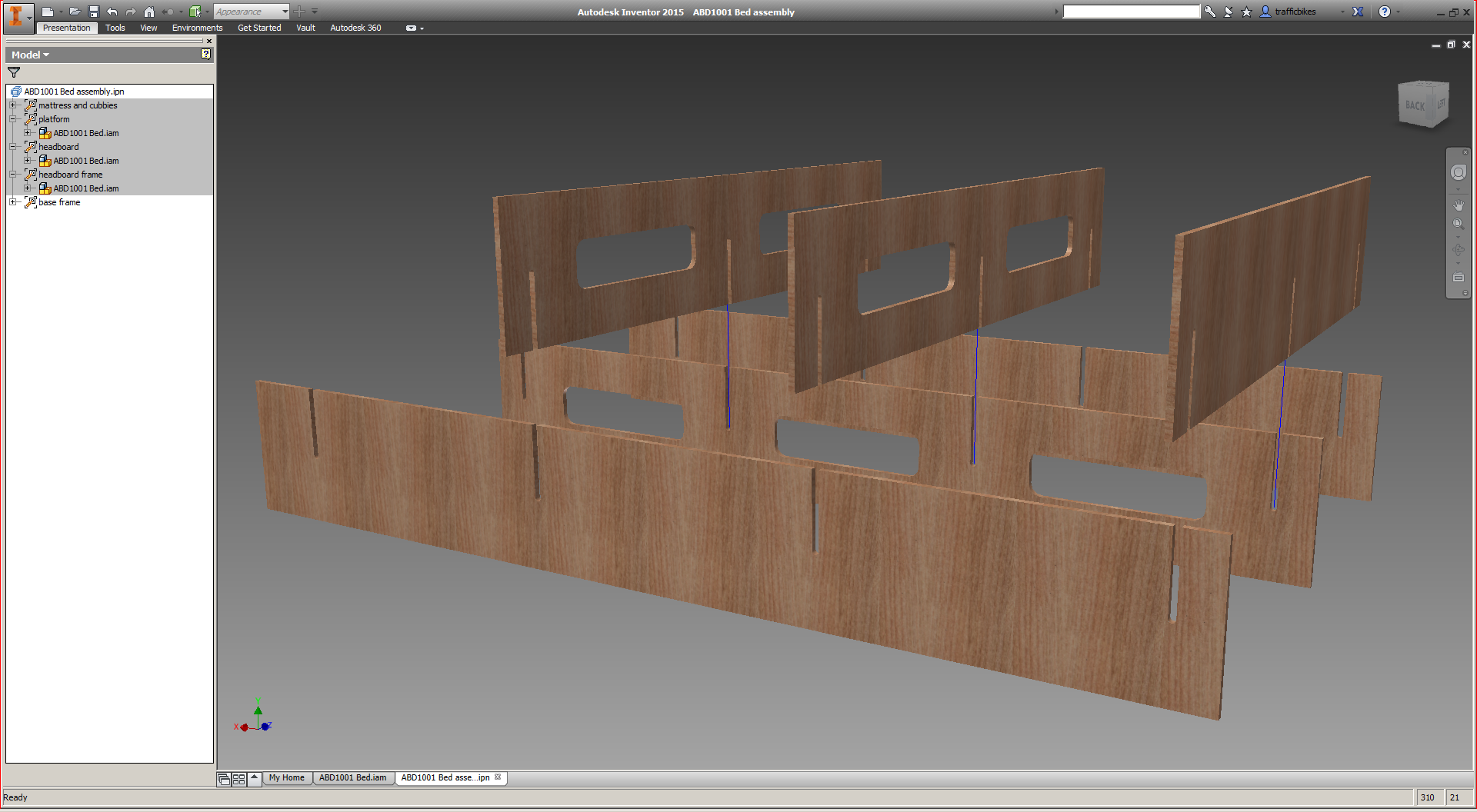

My bed project is coming along. The Inventor model is done (minus possibly some marginal edits) and I'm now processing it for production.

The way this will work: I buy ~20 sheets of cabinet grade plywood (probably black walnut, from Robert's Plywood) and have it shipped to Old World Moulding. They'll take my part list and cut the pieces up in a big overhead router. The parts will then be finished with a light, clear polyurethane.

In order to make sure that all the pieces have the intended grain orientation, Paul @ Old World asked me to lay them all out in AutoCAD. Which totally makes sense.

Except that I've basically never used AutoCAD. I played with it a bit as a kid (incidentally, it was also on a bed project), but I've only used it in passing as an adult.

Anyway, I broke it out today and I think the results are passable. It took me a while to get the basics (units, etc) down, but I drew a bunch of 4'x8' rectangles to show the plywood sheet sizes, and then exported each part's face as a DXF and copy/pasted it onto a piece of plywood.

The result: Nineteen sheets should cover us for three full beds. I'm a little disappointed with some of the grain orientations, but it'll be fine. I'm also a bit worried about the nested parts (on the six nearly identical sheets on the left); we'll see what Paul says about that.

The only other thing of note is the red boxes on the right. Those parts have a beveled cut on one side, which needs to be done on a table saw (the router is only 2-axis), so I'm adding a bit of material to the parts.

I'm *hoping* that this shit gets cut this week. It'll be really nice to have a project wrap up :)

What I say when someone asks what I do:

I work for a company called Undercurrent; we do strategy consulting for really big corporations. Our work generally falls into three big categories.The first is product strategy; we help companies figure out what to build. Typically we're talking about digital products here, so it's along the lines of "we know we need a new website, but we don't really know what our website should *do.*"

The second is organizational design. Here our clients usually have a product that customers really want, but they're kinda bad at doing the work, so we help them figure out how to organize their team to be better.

The third is broader think-tank type stuff. There, we're brought in basically to be smart people who can provide an outside perspective on an industry or competitive landscape.

The Public Radio's Kickstarter raised upwards of $30k last night, and my inbox is *crazy.* Here's one response I wrote:

Thanks for your note, and the compliments. You bring up some serious (and warranted, I think) questions, and while I probably can't fully answer them (my inbox is going a little crazy), I did want to respond quickly.

First: We don't have a business plan per se, and I tend to think that's a *good* thing. There were a few possible outcomes of the campaign (fund at $25k, where we make them all by hand, or fund at an order of magnitude higher, where we need to scale and outsource production & logistics), and it was impossible to plan for them ahead of time. That said, we spent a *lot* of time going through those scenarios and feel confident (a bit surprised, but confident nonetheless) that we're well equipped to handle what comes.

Second: The Public Radio's design is whimsical, but our intentions are not. While the challenges we'll face moving forward are different than those we've managed previously, we're both serious, professional adults, and each of us has managed large scale projects (which carried bigger risks than The Public Radio does) in our careers. In short: We're are not taking our responsibilities here lightly.

Third: Price. This is fuzzier, but the bottom line is that we live in a free (ish) market, and The Public Radio is priced at what we thought the market would bear. Keep in mind, also, that electronic devices are *really* expensive to make in low quantities (anything less than 10,000 annually, with annual commitments and long lead times). The Public Radio will *not* make us rich, but we were sure to set the funding and reward levels such that we wouldn't go bankrupt, either.

All of that aside, we do appreciate your feedback - we've been working on this for a year and a half now, and it's great to hear that what we're doing is resonating in some way. Hopefully I answered some of your questions; if not, please let me know and I'll try to clear it up :)

Spencer

From last week's Freakonomics podcast, a conversation with Ed Glaeser about Gary Becker, an economist whose career was punctuated with unpopular - and brilliant - stances. Note, the references to wilderness are referring to periods where Becker studied subjects that were at the time considered taboo.

Dubner: I’m curious whether you think that there are any lessons to be learned from Gary Becker’s experience generally, and maybe how anybody who’s listening to this, whatever occupation or vocation they might be thinking about, could perhaps apply some of that determination of Gary Becker’s to their own lives?

Glaeser: I think Becker is different from many of the wilderness-years-type scientists that we think of in the sense that he was not somebody who came out of nowhere who had a brilliant idea and was mocked for it initially. He was someone who was part of a very well-established economics department, who had, early respect, early rewards in lots of different ways. But what’s different from many of us is that he didn’t in any sense rest on those, and he didn’t rest them not just in the sense that he kept working, although he worked like heck. He didn’t rest on them in the sense in which he decided to risk everything on every throw of the dice, right? He wanted to always be out there. He wanted to push as far as he could. He wanted be as risky; he wanted to risk going back into the wilderness even though he had, you know, gotten himself a seat in the throne room, right? And that’s what’s really special about him, it’s being in the wilderness by design, by choice. Here’s a guy who over and over again decided to take those risks, to court disaster, to be on the very edge, to go into rooms, to enter fields in which he knew that people were going to think that he was outrageous. He knew that people were going to denigrate his work. And yet he still did it. And that’s what made him so productive. And I think the challenge for all of us, particularly all of us who are in the idea business is it’s a reminder to try to push ourselves as much as possible to try to be different, to be unpopular often, to do things that are troubling to the status quo, that risk us being thought of as being, you know, less than we are.

I think this is done.

The New York Infrastructure Observatory's inaugural journey is coming up! We'll be heading to the nearest Amazon distribution facility, in Middletown, Delaware, and will be touring one of the most impressive logistical operations in existence. If you're interested, throw your hat in the ring here - spots are *extremely* limited for this one, but we'll do everything we can to get you in!

A few weeks ago.

From a great interview with Randall Munroe (of xkcd) on Fivethirtyeight:

One thing that bothers me is large numbers presented without context. We’re always seeing things like, “This canal project will require 1.15 million tons of concrete.” It’s presented as if it should mean something to us, as if numbers are inherently informative. So we feel like if we don’t understand it, it’s our fault.

But I have only a vague idea of what one ton of concrete looks like. I have no idea what to think of a million tons. Is that a lot? It’s clearly supposed to sound like a lot, because it has the word “million” in it. But on the other hand, “The Adventures of Pluto Nash” made $7 million at the box office, and it was one of the biggest flops in movie history.

It can be more useful to look for context. Is concrete a surprisingly large share of the project’s budget? Is the project going to consume more concrete than the rest of the state combined? Will this project use up a large share of the world’s concrete? Or is this just easy, space-filling trivia? A good rule of thumb might be, “If I added a zero to this number, would the sentence containing it mean something different to me?” If the answer is “no,” maybe the number has no business being in the sentence in the first place.

From an interesting article about placebos and nocebos:

Although it is hard to imagine that nocebos would be purposely used in the practice of Western biomedicine, it is very likely that the nocebo effect is much more prevalent than either patients or physicians recognize. For example, when doctors highlight the potential side effects of new medications, such as GI distress or sexual dysfunction, patients complain of these much more frequently than when they are minimized. The same is true with pain caused by medical procedures: Women in labor who are given an epidural anesthetic are much more likely to report discomfort if the procedure is described beforehand as being more, rather than less, painful.

People are weird.