When I went to Taiwan last year with Brilliant Bicycle Co., I wrote a few posts that described the trip & what we saw there. But I never linked to Jacob Krupnick's videos of the trip, which do a much better job of relaying the mood & feel of the trip. So, here goes.

First, the tire factory (see my notes here):

Second, the cardboard box factory (see my notes here):

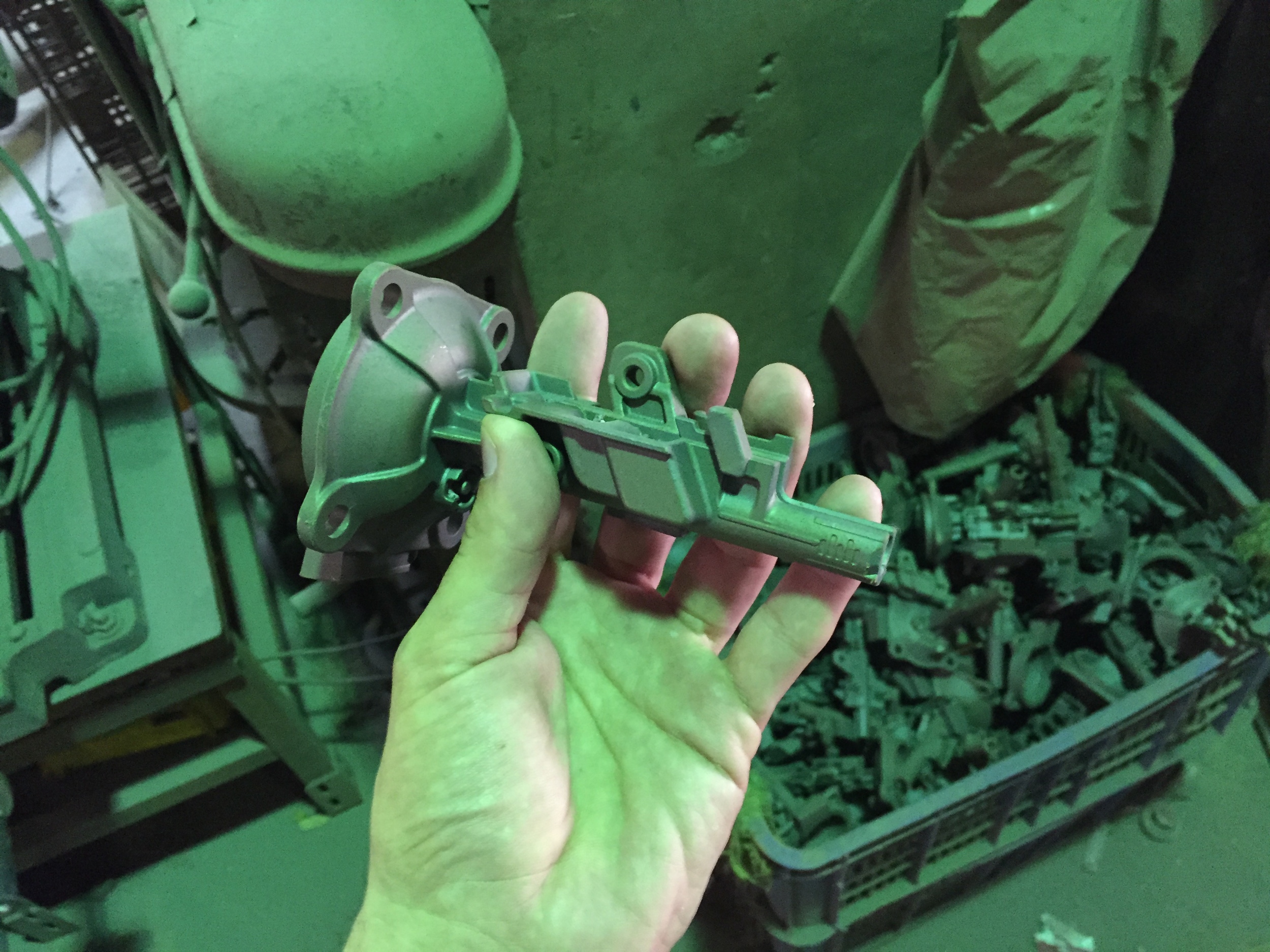

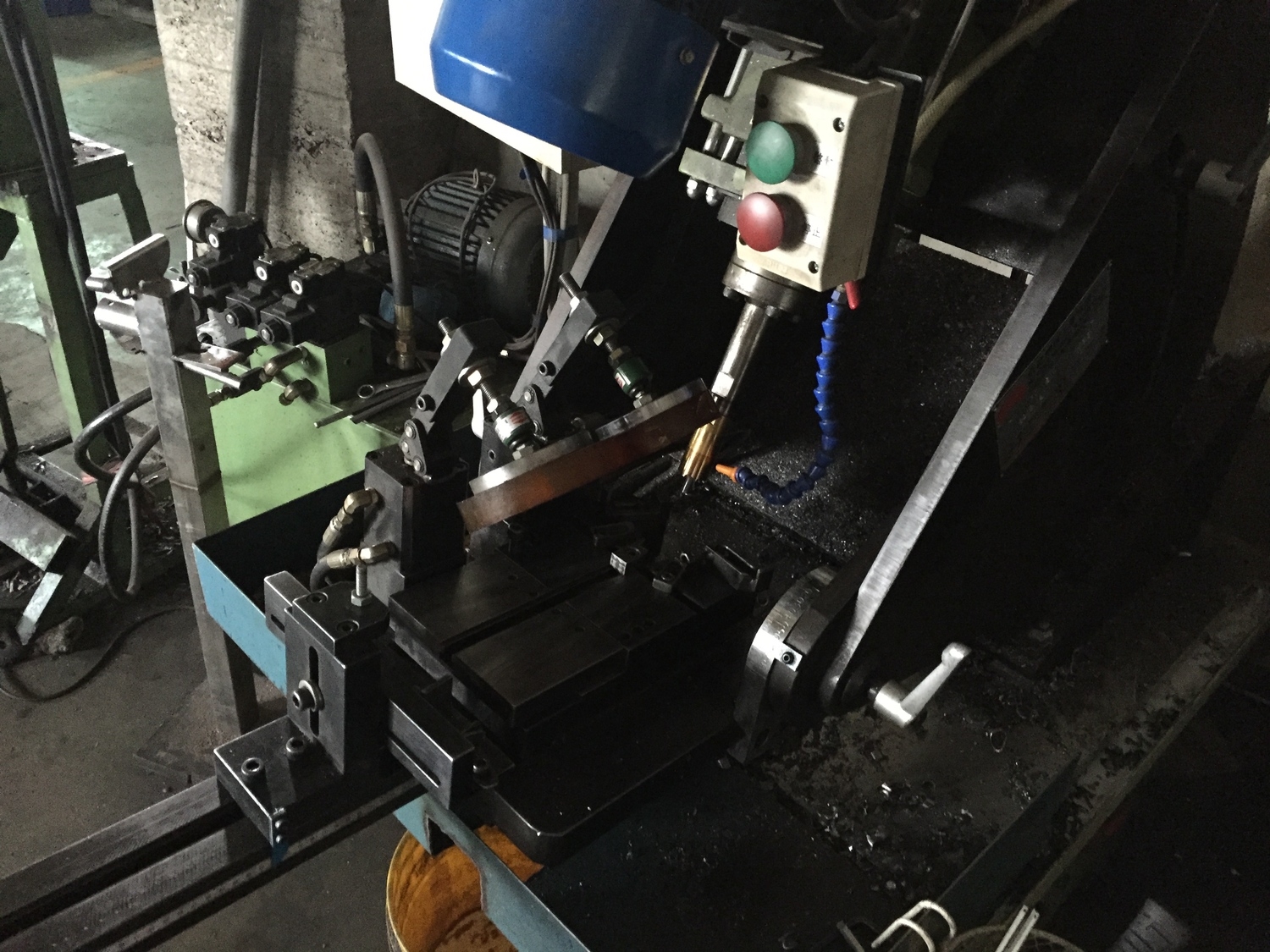

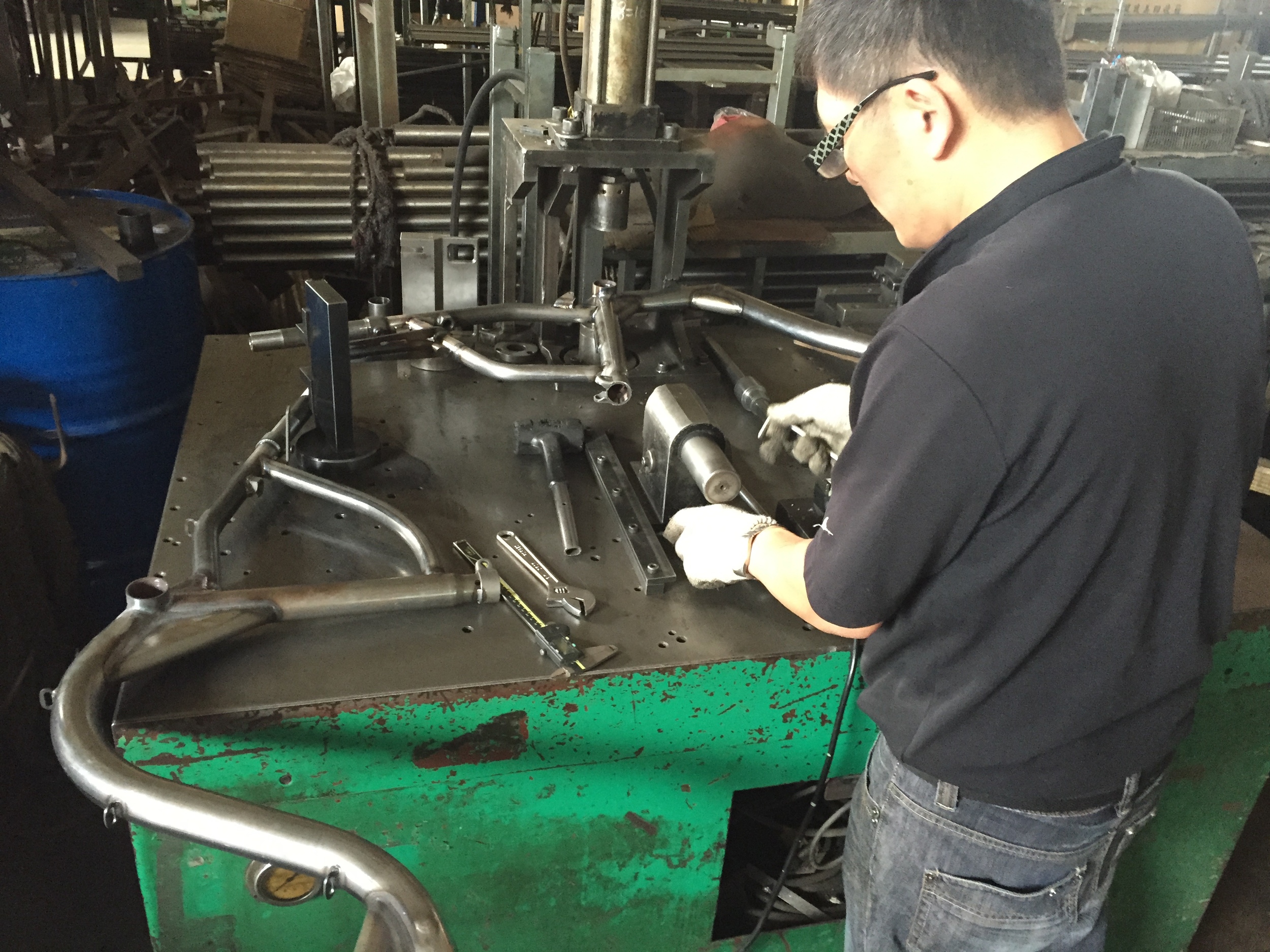

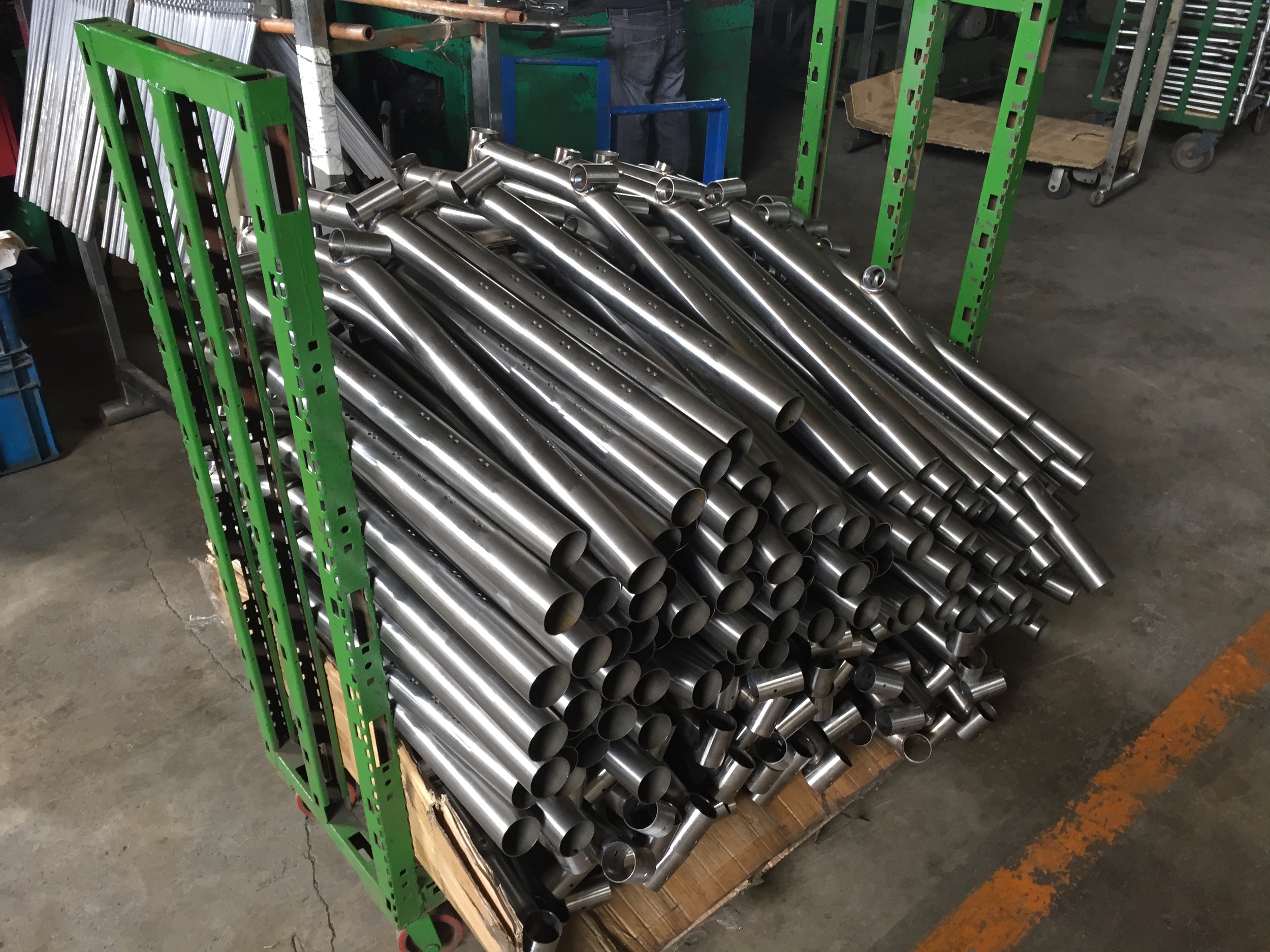

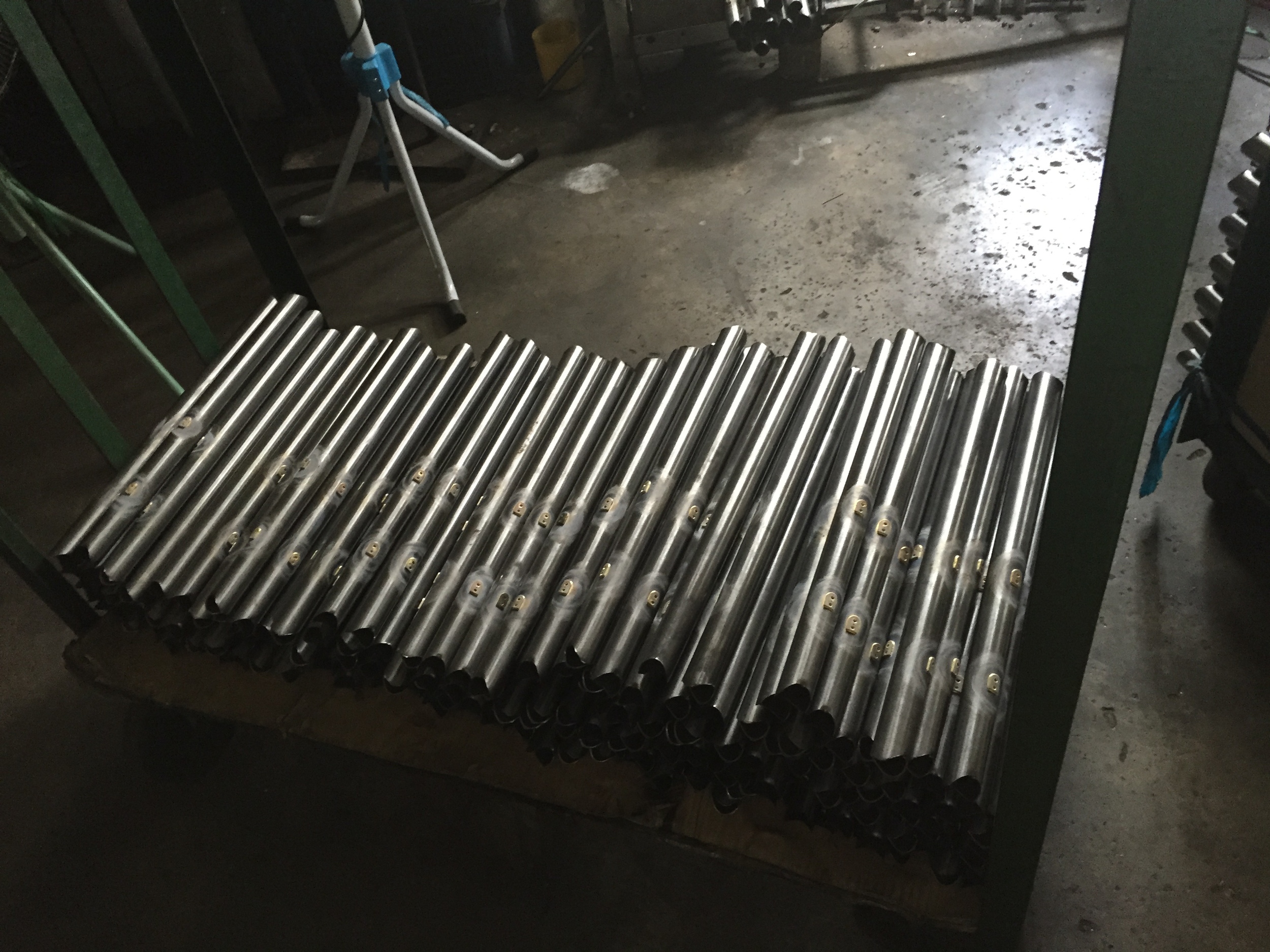

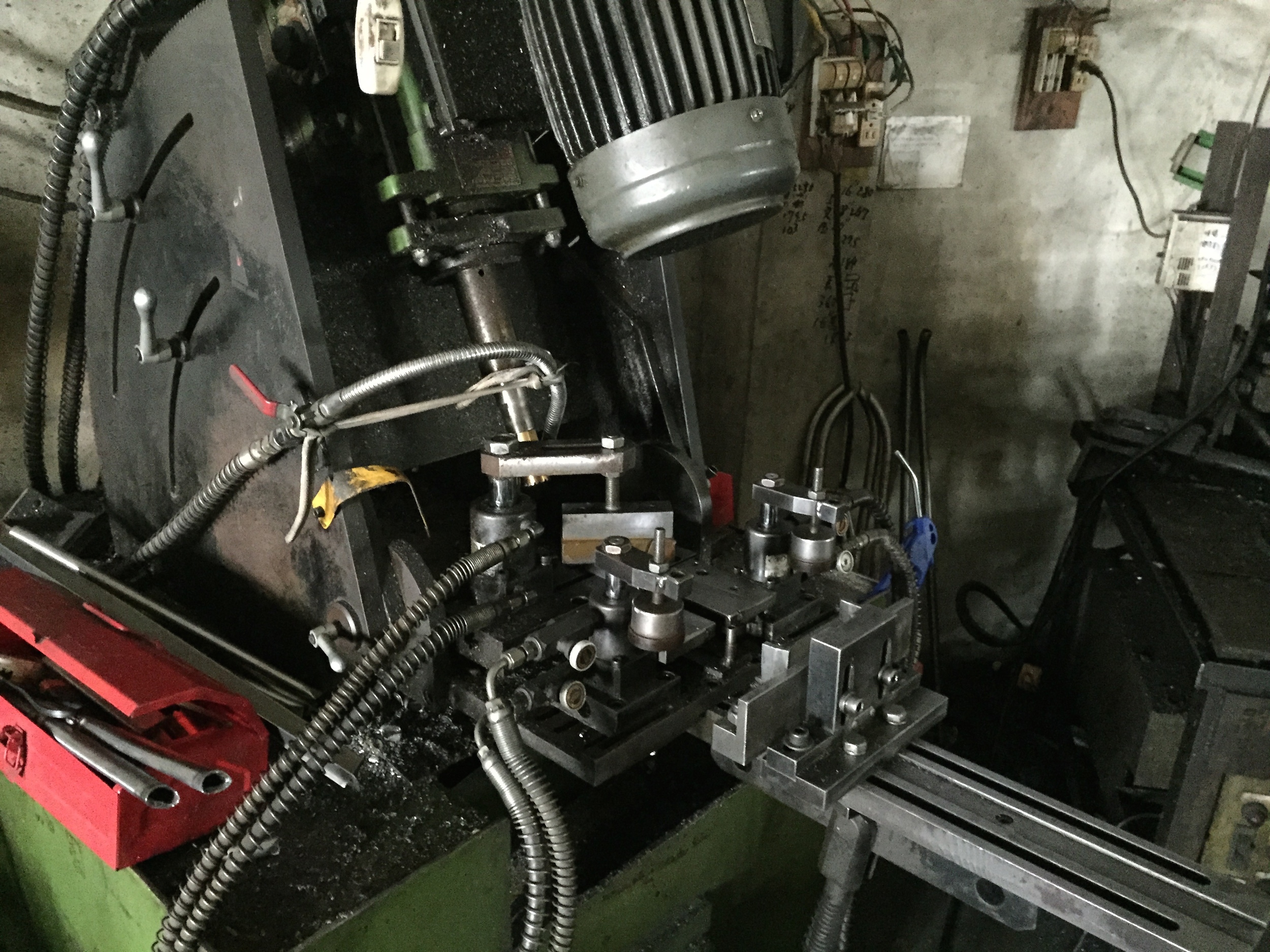

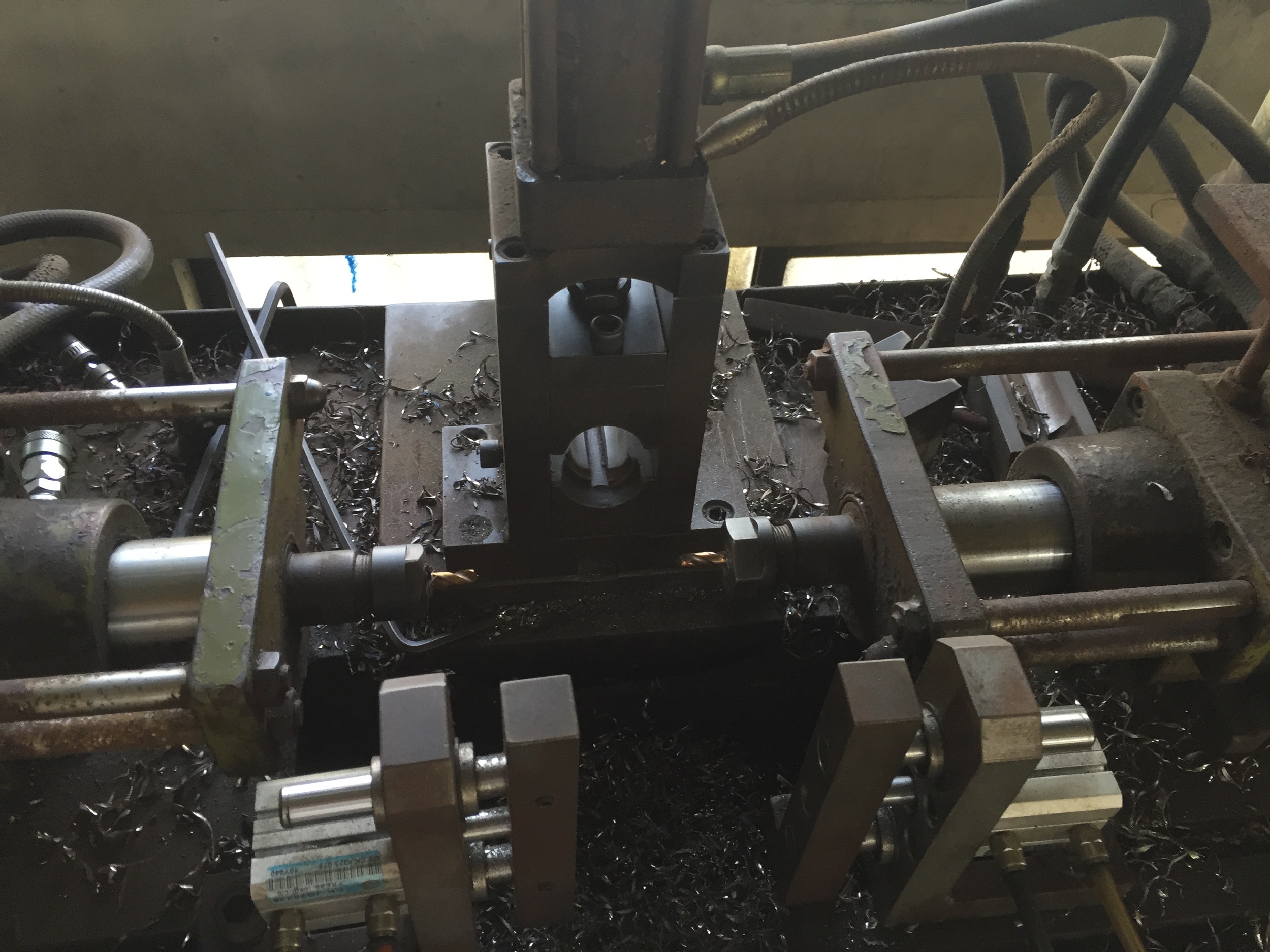

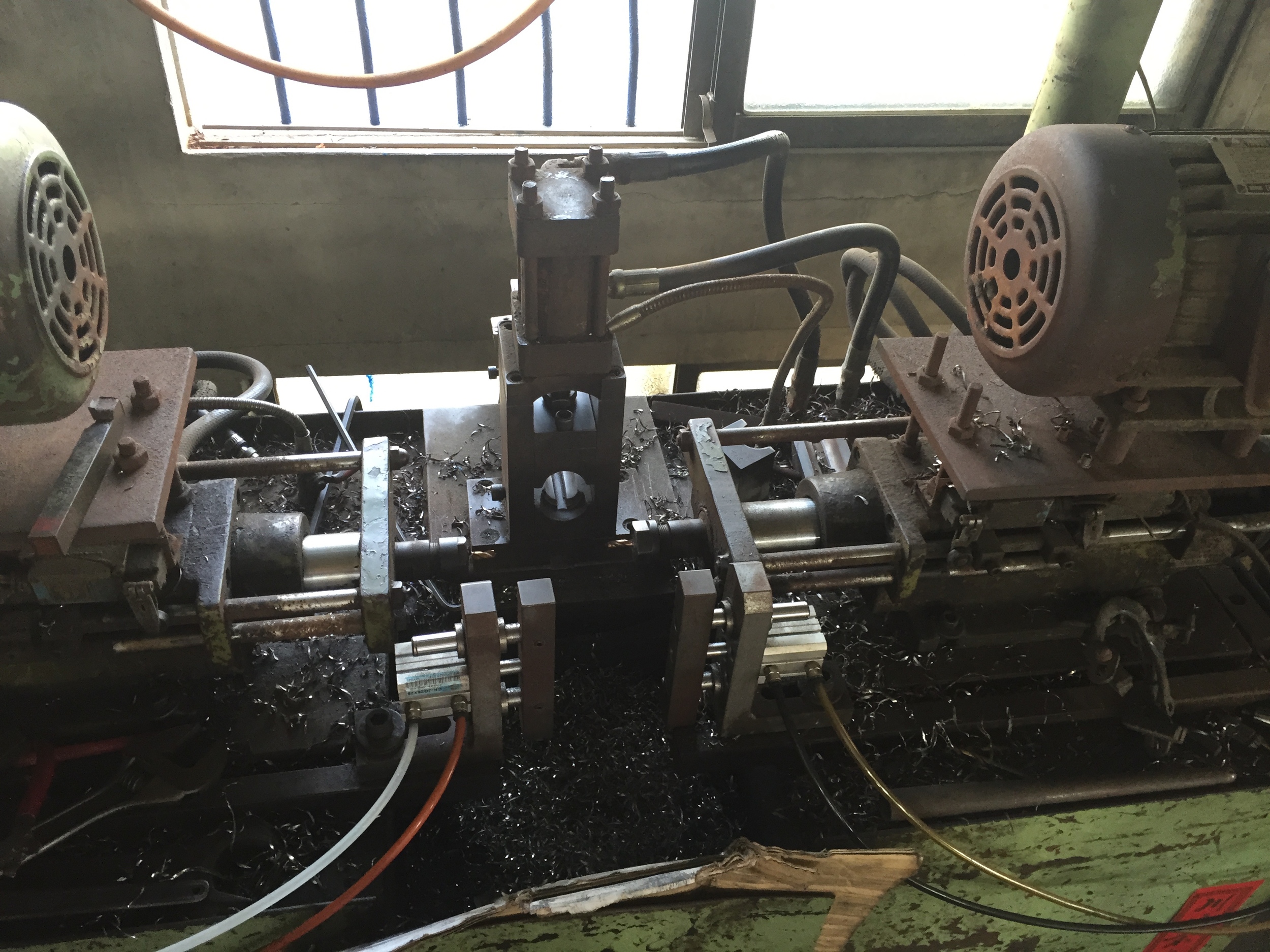

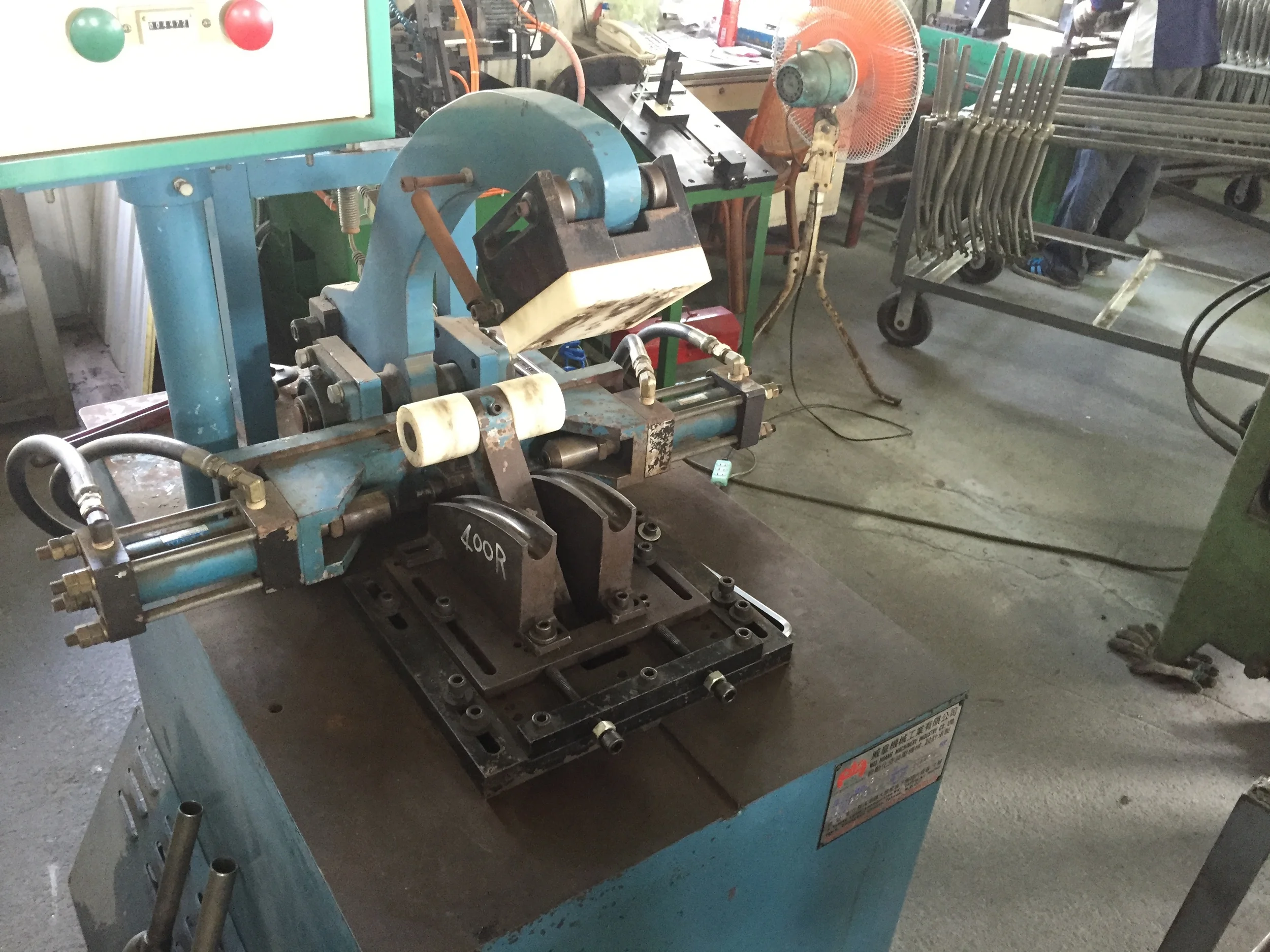

Third, the fork factory (see my notes here):

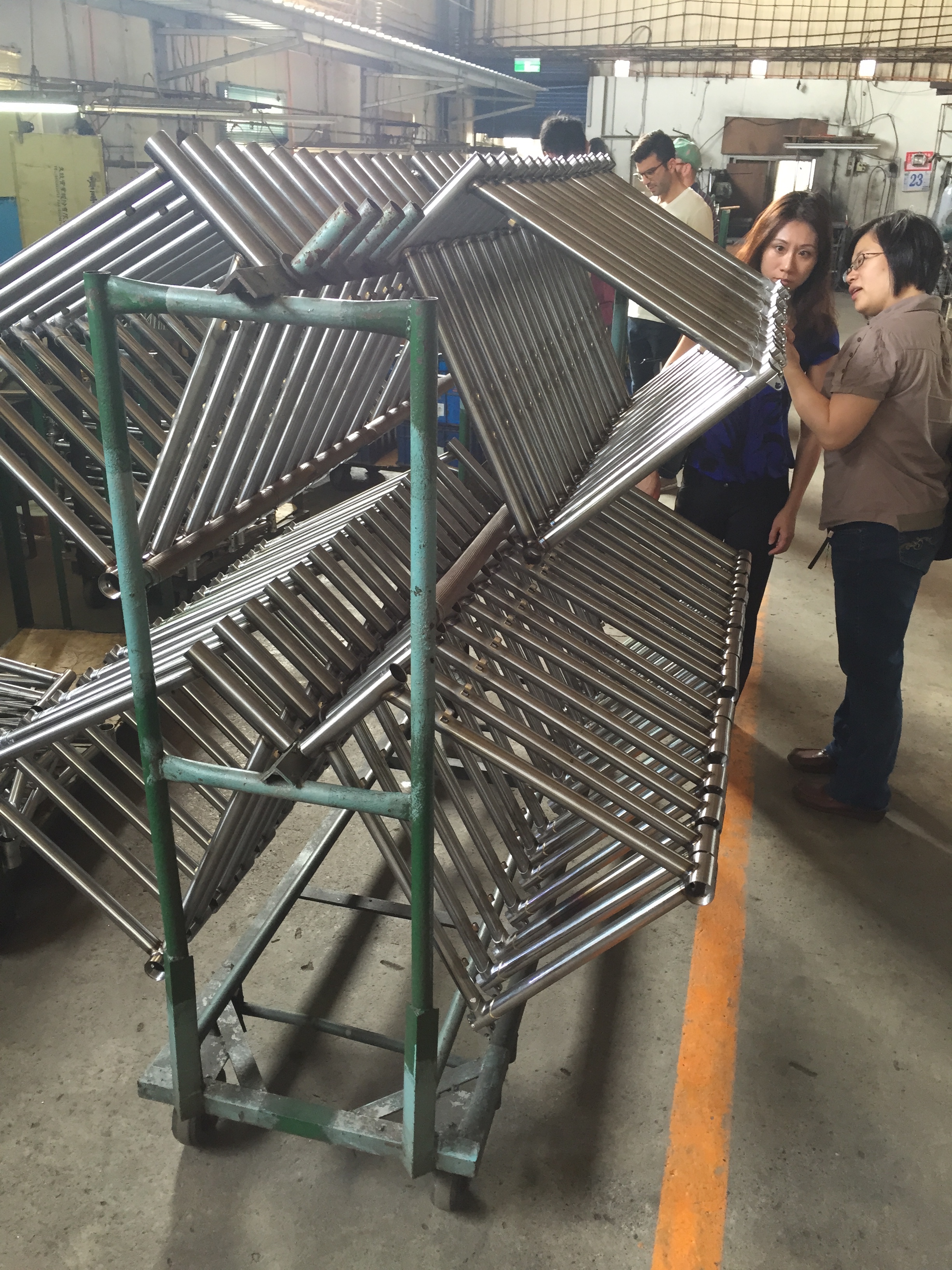

Fourth, the frame factory (see my notes here):

Fifth, the final assembly shop (see my notes here):

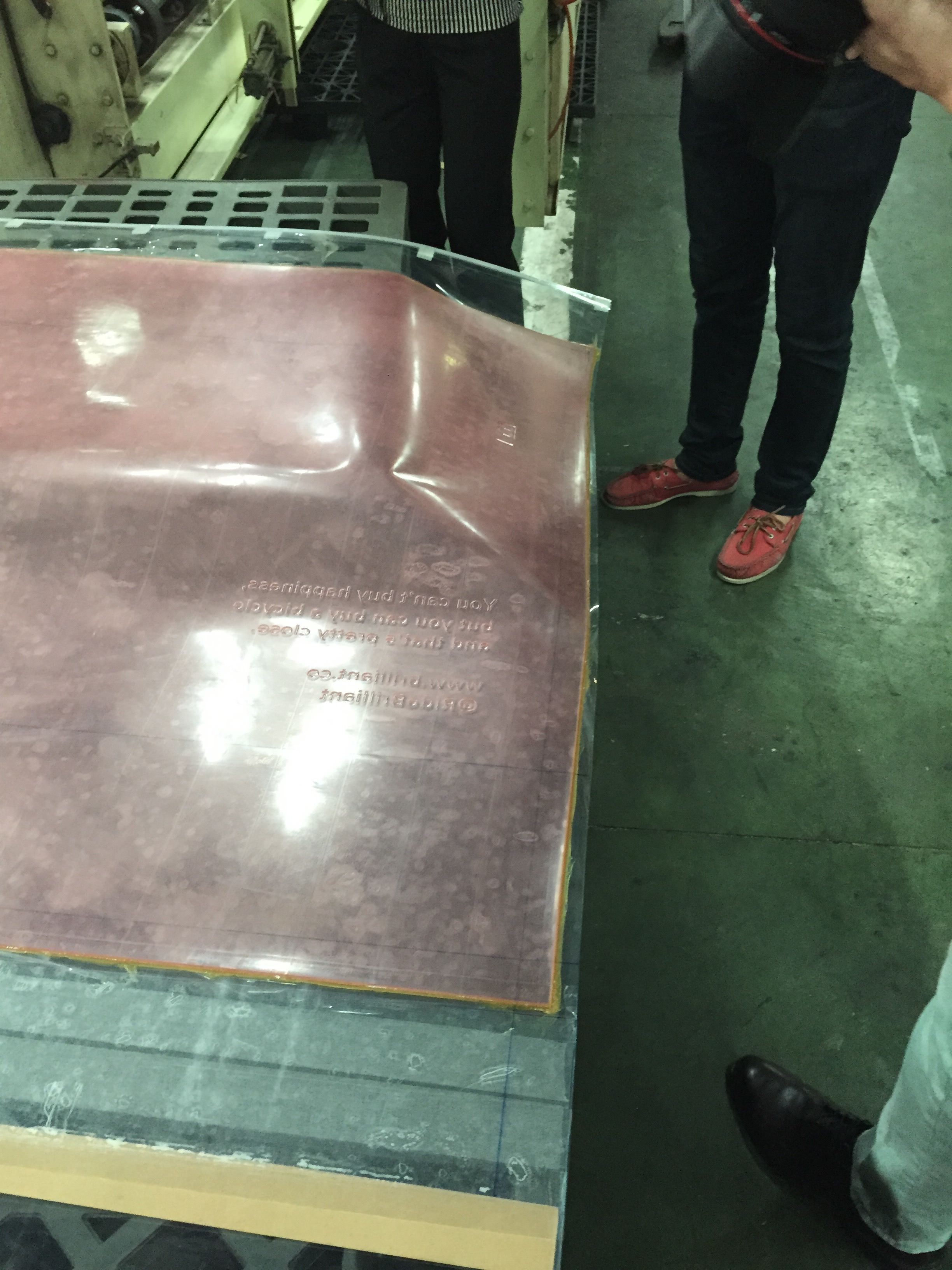

Sixth, the saddle shop (no notes from me, sorry):

Seventh, the paint shop (ditto):