Flowchart

This is ambitious and possibly a little overdone. RE: My parts storage system feature requirements. Note, you can see a bigger version of this chart here.

If anyone's got feedback or thoughts on the flowchart specifically, I'm all ears. If you're actually interested in the product... well, holler.

Oh, also LucidChart is kinda cool.

Playing, a few months ago

Just a pretty diagram, showing some ideas for a marine monitoring system I was thinking about a few months ago.

I like it when technical drawings include depictions of something physical, too. Whatever about anti-skeuomorphism, right?

Cloth

This 3D simulation, by a guy named Rusty Smith, is awesome. Found on GrabCAD.

Naked

The moment that you feel that, just possibly, you’re walking down the street naked, exposing too much of your heart and your mind and what exists on the inside, showing too much of yourself. That’s the moment you may be starting to get it right.

Neil Gaiman. Via Brad Feld and Tim Ferriss.

Stack-O-Vocals

The vocal tracks on the deluxe version of Pet Sounds are just crazy. The way they drop down into the bridge on "Wouldn't it be Nice" is really incredible.

Not about form

From Vanity Fair's recent piece on Jony Ive and Marc Newson. Emphasis mine.

“We are both obsessed with the way things are made,” Newson said. “The Georg Jensen pitcher—I’m not even sure I love the way it looks, but I love how it is made starting with a sheet of silver.”

“We seldom talk about shapes,” Ive said, referring to his conversations with Newson. “We talk about process and materials and how they work.”

“It’s not about form, really—it’s about a lot of other things,” Newson said. Both designers are fascinated by materials; they understand that the properties of a material affect the way an object is made, and that the way it is made ought to have some connection to the way it looks. Theirs is a physical world, and for all that their shared sensibility might seem to be at the cutting edge, it is really a different thing entirely from the avant-garde in design today, which is the realm of the 3-D printer, where digital technology creates an object at the push of a button, craftsmanship is irrelevant, and the virtual object on the computer screen can be more alluring than the real thing.

Ive is the son of an English silversmith, and Newson, who grew up in Australia, studied jewelry design and sculpture; both were raised to value craft above all. It’s ironic that Ive, who has had such a big hand in the rise of digital technology, is made so unhappy, even angry, by the way that technology has led to a greater distance between designers and hands-on, material-shaping skills. “We are in an unusual time in which objects are designed graphically, on a computer,” Ive said. “Now we have people graduating from college who don’t know how to make something themselves. It’s only then that you understand the characteristics of a material and how you honor that in the shaping. Until you’ve actually pushed metal around and done it yourself, you don’t understand.”

I should begin by saying that while I take issue with the finer points of Newson & Ive's comments - and with much of the pontificating that the Vanity Fair writer engages in - I found it refreshing to read this passage. I value my time building physical objects immensely, and while I'm somewhat ambivalent about some of the career decisions I've made, I'm proud of the artifacts that exist as a result.

Were I a bit more pushy re: my design career, I'd tout the above passage as gospel. But the truth is that I'm not sure I believe that designers *need* to make things first, and anyway it's not like the design world agrees wholeheartedly with Ive either (my file handling skills just aren't that much of a selling point, and with just cause).

I also take issue with the cynicism expressed re: craftsmanship being irrelevant in the age of the 3D printer. I see no a priori reason for that to be the case, and if it's indeed the way the design world sees advanced manufacturing, I'm certainly unaware of it.

My time as a craftsman was brief; I shed the term almost as soon as it could reasonably have been applied to my work. But whatever its connotations are, I'm sure that my transition to digital design and manufacturing has not infringed. Craftsmanship - whatever it consists of - does not directly correlate with the size of one's calluses. Craftsmanship is an attitude about work and a focus on a particular (and generally small) skillset. And in my opinion, the romanticization of craftsmanship that I see around me (and in the tech world specifically) is unproductive and dangerous.

Side note: I can't tell exactly which pitcher these dudes are drinking out of, but I'm pretty sure it's fancy as hell.

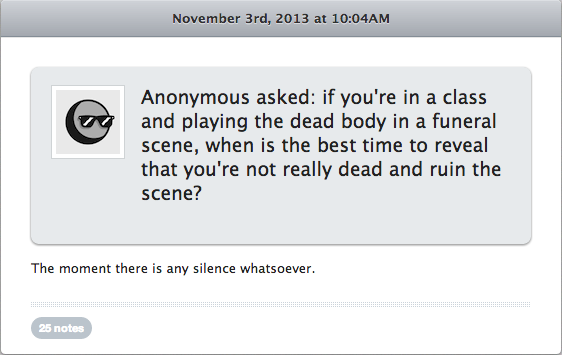

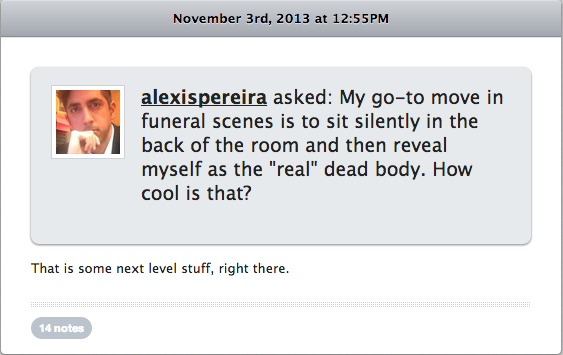

Improv Nonsense

Two great posts on Improv Nonsense today. The first serves as a setup:

And the second is the real punchline:

Eames

Update: Dummy Headset

Short update on my Dummy Headset project!

First, I took v1 (the non-lightened version) and installed it on a frame I lad lying around. In order to do so, I had to tap threads into the holes that were SLA printed right into the parts, which I did by hand. Shapeways and the other 3D printing houses just won't do secondary operations (this is dumb and will in time change), but it only took a few minutes to do. For mockup purposes I used some cup point set screws that I had in my shop (the final version will have soft tipped set screws). The end result was pretty slick - my frameset now has the fork semi-permanently attached, and the whole thing is totally secure.

Of note: Here's a photo of the original dummy headset that I turned on my late circa 2010. I used little thumb screws on it, which were kind of convenient, but the overall look is too blocky for my eyes.

After mocking the whole thing up and seeing that it functioned as intended, I went ahead and ordered v2 of the parts, which are internally relieved to reduce build mass. They came a week or two ago, and I'm happy to say that I think they'll work just fine. The internal ribs probably aren't totally necessary, but they're kind of a cool feature and would be *impossible* to be made via conventional methods. I may end up removing most of them, but for this version I'm happy to have included them.

I also grabbed a few soft tipped set screws from McMaster, and am looking forward to seeing how they work. The nylon tipped one would be for carbon fiber steerers, which are pretty delicate and don't want a metal screw digging into them. The brass tipped screws would be for steel and aluminum steerers, which are much more durable.

I haven't had time to tap the holes in this version or install them on a frameset yet, but I have no reason to think they'll work anything other than perfectly. At that point I need to determine whether it's worth trying to get them injection molded or CNC machined in bulk. These SLA versions cost me about $20 for the set. If I had to guess, I'd say that they'd run $5-10/set for CNC machined and $2-3/set injection molded (in quantities of 100s, plus $2-3K in tooling and setup).

An old jig

Fixture building comprises a lot of a manufacturer's time, regardless of the scale of the operation. For small shops, designing fixtures that can be used repeatedly for different customers is extremely useful. I faced this challenge a number of times when I was working on bikes, and spent a lot of time setting up fixtures that helped my productivity a lot.

In 2010, I built the brake boss mitering jig below. It mounts to a tiny little rotary table that I bought for my Benchmaster, itself the tiniest horizontal mill that I owned and still one of my favorite tools.

It seems quaint, but little productivity tools like this are how shit gets done in even big production style factories around the world. I kid you not - little manual mills, drill presses and lathes are in operation as I write this, performing some little repeatable operation on high precision parts for demanding customers.

Eventually a lot of these things are likely to be sold for scrap and passed down the line to developing economies. I've been to a few tooling auctions, and have seen 75 year old punch and foot presses that weigh (literally) a ton being sold for under $100. I understood that they would be loaded into a container and shipped to Asia, and it's likely that they got a new life there making good parts for another decade or so at least.

I generally think that that lifecycle is a healthy one, though it does have the strange effect that nowadays, even the most industrious kids are likely to end up knowing additive manufacturing in lieu of conventional (mostly subtractive) methods. Schools around the country are buying up MakerBots by the truckloads, and with good cause - to fail to do so would be an offense on par with teaching me cursive in 1992, when what I should have been learning was C or HTML. But all those 3D printers have got to go somewhere, and I suspect [citation needed] that they're supplanting Heavy Tens and J-Heads, which anyway don't get too much use as it is.

While I'm reasonably unromantic about that transition, it does strike me that subtractive methods are likely to remain, for the long time, significantly more efficient and effective for making certain types of products. Just as CNC machining hasn't replaced casting, forging, and sheet fabrication, additive manufacturing won't totally replace those methods either. All of these tools will, instead, complement each other - and the institutional knowledge pertaining to traditional manufacturing will, I hope, be not supplanted but enriched by newer paradigms of manufacturing philosophy.

A thing from a while back

In 2009, I made a trio of seat lugs. They were intended for a batch of Dutch bikes that remain not much more than an idea.

The way one makes these things is silly, but it offers the designer considerable creative freedom. You essentially build the joint twice, and carve a lug in between. I made these when my file handling was at its zenith, which is both worth noting (file handling is underrated) and also a totally silly skill to possess.

Can

So, 3dfile.io supports Autodesk Inventor *and* Solidworks files right out of the box. Sketchfab, on the other hand, only does these dumb tessellated formats that all the 3D printing people use.

Note that the body appearances in this viewer actually aren't what I have them as in Inventor; apparently 3dfile.io is applying some sort of changes to the file when I upload it. Regardless, not having to export as a different file format is great. I don't see how I'll be using Sketchfab at all anymore.

Oh. Also, I modeled a can. Pretty neat, huh?

Two types of Uncertainty

What I think about when I'm working alone.

In my career, I have experienced two primary types of uncertainty. They are characteristically different in nature, and produce correspondingly distinct effects on my mood and outlook. They are uncertainty that what I'm working on will be significant, and uncertainty that what I'm working on will be noticed at all.

I am, like anyone else, motivated by self interest. I hope for some degree of public buy-in on the things that I work on and care about. I want people, and the market, to like me, and to think that the work I produce is worth paying for. And while I can be brash in certain circumstances, I remain deeply uncertain about the degree to which the market will value what I do.

But worse than that is the uncertainty of whether anyone will notice. I've spent much of my career working alone, and I accept that one needs to appreciate his own experiences outside of the possibility that anyone else cares about them. But that prospect remains a challenge to me. The idea that I will have struggled to complete things that nobody will see, that I will have felt deeply about things that nobody will be aware of, that I will have had experiences that I'll never be able to share with anyone else... it's a haunting sensation.

At the same time, there are things that are difficult to share - not because the act of sharing them is uncomfortable, but because they're not particularly relevant to anyone but myself. I write about as much of my life as I can here, but it's unclear how I would share a moment that transpired years ago and remains with me - but which, in itself, doesn't amount to much.

So, what to do? About a year ago, I brought my German Shepherd, Libo, on a weeklong trip to Northern California, where I lived 2001-2007. I got Libo later, after I had moved back to the East Coast, and going there with him was powerful in ways I hadn't anticipated. There was no way to communicate to him how lonely I was for much of my time there, and how significant it was to me that I was now able to share something about that time of my life with him. It was deeply gratifying, though the logic doesn't really add up. He had no idea where we were, and my emotional state was (I'm sure) as opaque to him then as it usually is.

Writing here is much the same. I throw bits of myself into the ether, but rarely do I hear anything back. If somebody is reading this now then I'm certainly unaware of it, and although I wish constantly for feedback, I accept that I won't always get it. It's only lonely if you call it that, but sometimes it's hard to know what else to call it.

No happy ending here. Aaaand... back to work!

:)

Base

:)

Chart Game

:)

I, of course, own them all :/

Topper

Recently.

The number and complexity of the surfaces here is just dumb, and it's my fault. I ended up rebuilding it with a solid model, though I'd like to revisit the surface model again.

Luck

I guess I'm a decade late to this party, but this interview with Dr. Richard Wiseman about his book "The Luck Factor" is really great. Excerpts:

BUT THE BUSINESS CULTURE TYPICALLY WORSHIPS DRIVE -- SETTING A GOAL, SINGLE-MINDEDLY PURSUING IT, AND PLOWING PAST OBSTACLES. ARE YOU ARGUING THAT, TO BE MORE LUCKY, WE NEED TO BE LESS FOCUSED?

This is one of the most counterintuitive ideas. We are traditionally taught to be really focused, to be really driven, to try really hard at tasks. But in the real world, you've got opportunities all around you. And if you're driven in one direction, you're not going to spot the others. It's about getting people to have various game plans running in their heads. Unlucky people, if they go to a party wanting to meet the love of their life, end up not meeting people who might become close friends or people who might help them in their careers. Being relaxed and open allows lucky people to see what's around them and to maximize what's around them.

WHAT ARE SOME OF THE WAYS THAT LUCKY PEOPLE THINK DIFFERENTLY FROM UNLUCKY PEOPLE?

One way is to be open to new experiences. Unlucky people are stuck in routines. When they see something new, they want no part of it. Lucky people always want something new. They're prepared to take risks and relaxed enough to see the opportunities in the first place.

BUT CAN WE ACKNOWLEDGE THAT SOMETIMES BAD STUFF -- CAR ACCIDENTS, NATURAL DISASTERS -- JUST HAPPENS? SOMETIMES IT'S PURELY BAD, AND THERE'S NOTHING GOOD ABOUT IT.

I've never heard that from a lucky person.

Startups Should Write Prose

And you probably should, too.

Note: I wrote this post in response to Eric Paley's "Startups Shouldn't Write Prose" post. While I disagree with the premises of his argument, I do concur with a number of his conclusions (e.g. that formal business plans have limited utility). Regardless, I have respect for his thoughts on the subject, and appreciate the ideas he puts forward in the original post.

I am a big fan of accepting and accounting for uncertainty. Uncertainty has been a big part of my life, and I suspect that its role in the lives of those around me will only increase over time. In general, I think that's okay. Partly because I think it's fun to embrace uncertainty, but mostly out of my feeling that, as Chuck Klosterman wrote, "the future makes the rules, so there's no point in being mad when the future wins." My best play is to construct general theories about what the world will look like in the future, and then try to position myself in such a way that the work I'm doing will be rewarded and the things I care about will be allowed to grow.

It's a tough thing to do. Humans are mediocre predictors, and they're terrible at understanding and evaluating predictions (see Subjective Validation, the Forer Effect, and whatever your friends think about their horoscopes). In philosophy and math, formal argumentation takes a large role here; it can be very helpful in evaluating the methods of reasoning used by predictions in general.

While I was a passable student of higher order logic in college, formal argumentation has played a large role in how I understand the world. But I accept that my experience is not universal, and I care more about getting my point across than I do about the medium. And the fact of the matter is that prose remains my best tool for communicating complex ideas - and I suspect that the same is the case for most individuals and brands.

Startups, like the rest of us, deal in uncertainty. A startup is, in Steve Blank's definition, "an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model." That is, startups are inherently uncertain what business they're in, or what business model they will organize themselves by. The primary obstacle in any startup's path is figuring out what they can make that people will want.

In the early stages of a startup's life, investors constitute something of a separate class of customer; as funding options broaden (see crowdfunding; the SEC's recent actions), this line will blur even more. Regardless, all of a project's stakeholders will require some form of communication, and in the case of investors, a startup's goal is to show how and why its business will be successful. There are many aspects to that equation, of course. But they generally include at least an implicit argument, which is communicated in a variety of ways. Startups need to communicate that there is (or will be) demand for what they're working on, and they need to show that they are uniquely positioned to meet that demand. These are complex ideas, and not to be taken lightly. Moreover, investors won't want to feel like they're being argued into something, so startups would be wise to let the logic of their product, and the makeup of the team behind it, speak for itself.

Slide decks do not generally convey argumentative structure well. Arguments are not constructed hierarchically, but slide decks present information in a top-down, slide-by-slide manner. They also measure information in discrete parts - the slide being the smallest unit of measurement. But arguments don't conveniently break up well into slide-sized pieces, and the result is that key points are often truncated in order to adhere to a slide's predetermined size.

What slides are good at is creating a rhythm during a presentation. For many presenters, this is highly useful - but to my mind, the content of the argument should not be sacrificed for the sake of presentation, and any presentation method that requires arguments to be abbreviated should be avoided. Startups should avoid hubris at all costs - and the presentation of an abbreviated argument in order to make a stakeholder easier to convince is not a step on that right path. As Edward Tufte wrote:

The pushy PowerPoint style imposes itself on the audience and, at times, seeks to set up a dominance relationship between speaker and audience...A better metaphor for presentations is good teaching. Teachers seek to explain something with credibility, which is what many presentations are trying to do. The core ideas of teaching - explanation, reasoning, finding things out, questioning, content, evidence, credible authority not patronizing authoritarianism - are contrary to the hierarchical market-pitch approach.

Slide pitches encourage a presenter to elide the deductive reasoning of his company's work, and let the post hoc ergo propter hoc nature of the presentation seduce his audience. As Tufte says, "PowerPoint actively facilitates the making of lightweight presentations," and I would argue that startups should avoid lightweight presentations - especially when dealing with early stage investors.

Prose, on the other hand, is accessible, thorough and can be highly evocative. It's also platform independent, and doesn't require the author to be present to provide context to slides which have been abbreviated in order to achieve a consistent tempo. Prose can be used to convey complex, nuanced arguments, and it does so in such a way as to communicate argumentative style and personal character.

Prose also has the benefit of requiring verbatim proofreading, forcing its author to literally read back an argument to himself. This process can be extremely helpful to a project in which all of the details haven't been ironed out, as weak points are often glaringly obvious when they're verbalized explicitly. Slide decks, on the other hand, allow authors to gloss over difficult points in the text, with the intent that they will be filled in verbally during the pitch. Careful audiences will pick up on these argumentative gaps, especially when reviewing notes after the presentation, and the result doesn't reflect well on the author's formidability or command of the subject matter.

Of course, all authors need to find their own paths towards personal argumentative style and brand image. But the benefit of complete sentences, whether in the form of blog posts, executive summaries, or soliloquies, should not be undervalued. Prose is a powerful tool, and there is a wealth of historical examples of well composed prose arguments which - long after their authors are gone - remain convincing and powerful (see Chomsky's early syntax work, Boolos on incompleteness, Plato (take your pick), or any nearby piece of scientific literature). It's possible that the same will someday be the case with the slide deck. But I suspect instead that it's a transitional technology, and that presentations relying on PowerPoint-like technologies will be largely forgotten. Written prose, on the other hand, will be with us in some form or another for a long time, and I'm not in a position to argue with the future on that point. I encourage young teams - and anyone wanting to convey their ideas to others - to do the same.

For anyone looking for a particularly acute parody of a slide deck, see Peter Norvig's Gettysburg Address. Note, though, that any medium has examples of poor execution - and please send along examples of especially good slide decks, if you've got them :)

Special thanks to Hope Reese and Nick Fletcher Park for editing.

Taguchi

From the Wikipedia page on Taguchi Methods. Genichi Taguchi was an engineer whose research focused largely on manufacturing tolerance design.

He therefore argued that quality engineering should start with an understanding of quality costs in various situations. In much conventional industrial engineering, the quality costs are simply represented by the number of items outside specification multiplied by the cost of rework or scrap. However, Taguchi insisted that manufacturers broaden their horizons to consider cost to society. Though the short-term costs may simply be those of non-conformance, any item manufactured away from nominal would result in some loss to the customer or the wider community through early wear-out; difficulties in interfacing with other parts, themselves probably wide of nominal; or the need to build in safety margins. These losses are externalities and are usually ignored by manufacturers, which are more interested in their private costs than social costs. Such externalities prevent markets from operating efficiently, according to analyses of public economics. Taguchi argued that such losses would inevitably find their way back to the originating corporation (in an effect similar to the tragedy of the commons), and that by working to minimise them, manufacturers would enhance brand reputation, win markets and generate profits.