The Public Radio is in preproduction.

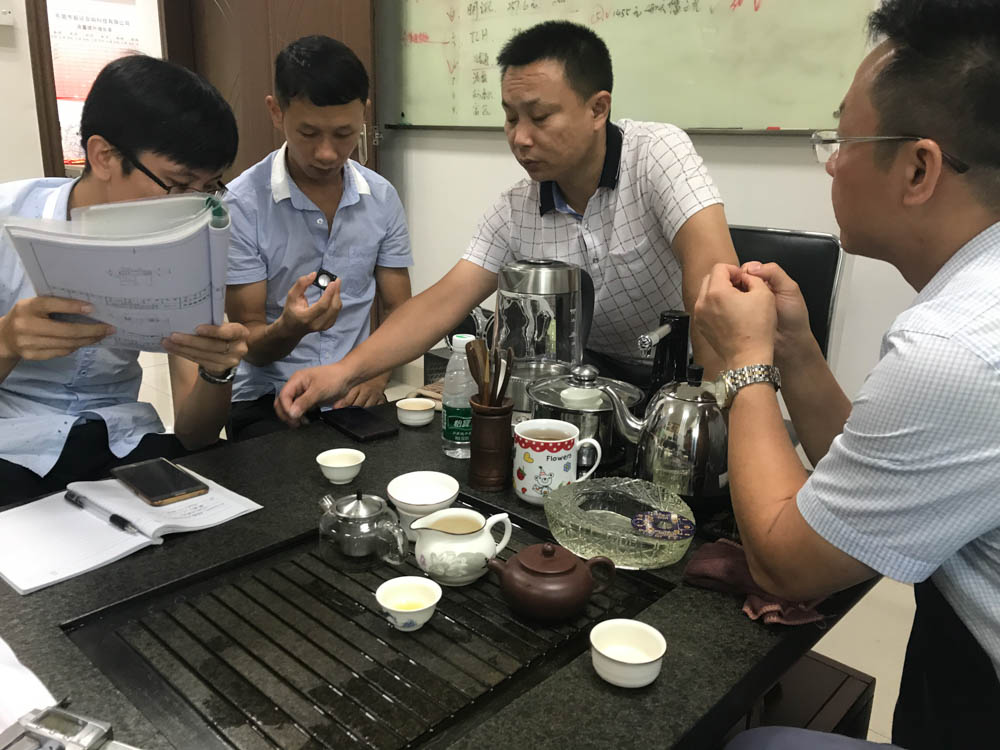

First: I spent part of week in Taiwan, Shenzhen, and Dongguan in late June visiting a few of our component suppliers, and parts started trickling in at our manufacturing partner last week. Proof:

A few notes here:

- A huge thanks to Lucas, who came with me to the speaker factory and was just generally a hospitable guy while I was in Hong Kong & Shenzhen. Thanks also to Kuji for showing me an awesome time (see this video) in Shenzhen.

- Visiting our speaker manufacturer for the second time (the first time was two years ago) was great. Knowing our suppliers is a real treat, and I've very much enjoyed working with them.

- Seeing the mold for our new custom speaker was big. This was an investment - both in the tool itself and in our relationship with our speaker factory - but it makes The Public Radio more robust and *much* easier to put together. It reduces the assembly's total number of parts and allows us to use larger screws, which are easier to handle and will take less time to install. That both saves us money and makes TPR an overall nicer product. This is also the second injection molded part I've ever designed and is *slightly* more complex than the one before it, so from a personal standpoint it was *really* fun to actually touch.

- China, as always, is just mind boggling. I especially appreciated Ofo, which is amazing.

Second: Since then, I've been dealing with our remaining procurement issues (mostly logistics & cash flow planning; some vendor management) and then hammering on our actual manufacturing plan. The Public Radio has an extremely simple user interface, and to create that there's a *ton* of work that goes into managing the assembly & fulfillment process. This involves a few special things:

- As Zach and I discussed with Gabe on The Prepared's podcast a few weeks ago, we've now got a fully custom order management database which coordinates customers, tuning frequencies, and shipping data (and a few other little things).

- An instance of Tulip, which will handle not only our assembly training but is also acting as the connective tissue between our database and the real world. Tulip will coordinate barcode scans, assembly steps, and our radio programming jig to keep everything in sync. It also logs productivity and can help track defects down the road. In short, it's awesome.

- Our radio programming jig. Josh is taking a crack at this (among other things :) now, and hoping to make it more reliable & robust than the ones that we used on the first batch of Public Radios two years ago.

These three things are *just* starting to really come together this week; I've got maybe a third of it all running on my desk right now.

Next up: We should have a fully functional prototype of our manufacturing system running in two weeks. We'll be testing it in NYC for about a week, and will then bring the whole thing to Chicago to fit it into Accelerated Assemblies' processes. By then we'll have all of our materials on site and, after a short run or two to iron out any kinks, will be in full production mode.

More soon :)