"hey, well - china sleepy."

as a recently freelance guy who's looking for some extra cash and every-possible-way to network, i've been moonlighting (daylighting) as a bike mechanic. this is not exactly a career move for me, but it turns out that working on bikes is something i'm halfway decent at - and, moreover, that diagnosing customers' reported issues is something that i'm well suited to. and anyway i do need the cash.

despite myself, i enjoy working there. the clientele are high end and polite, and my coworkers are totally pleasant people. they're kind, thoughtful, and respectful of each other and myself; i would even go so far as to say that i like them. i bring value to the shop, and the shop brings me value too, and there's a mutual respect that's important to have in one's life.

in a lot of ways, though, i'm not exactly one of the dudes. the kinds of things that i'm most interested in - structured systems; means of production; frameworks from which to assess the world - don't always fit into the shop discourse. i'm a stickler for argumentative reasoning, and in my experience, bike mechanics tend towards a top-down distribution of knowledge. it's not an uncommon or surprising tendency, and is one that i think is pervasive - to much benefit - in many industries. manufacturers distribute specific guidelines for how parts should be installed, used and serviced, and individual users are instructed to follow those guidelines closely. it is not a system that rewards innovation. then again, neither is commercial airline navigation, and as Atul Gawande has documented so well, the track record of professions which implement and follow preplanned procedures usually have lower levels of failure.

i hesitate to say that i pick fights about, for instance, whether a torque wrench should be stored at its lowest setting regardless of the consequences. more likely, i suspect, is the exact opposite relationship. i consider the null hypothesis because of the consequences. not only does a rigorous examination of an argument or statement of fact ostensibly increase the likelihood of my making an accurate judgment, but it has a significant social effect as well - and not one that is exclusively positive. and while i can't accurately say that i enjoy being alone in insisting that a particular widely held opinion might be wrong, i also can't deny that i have tended to put myself in that position time and time again. what this says about me and my ultimate desire to be liked - or disliked, as the case may be - i can only surmise.

- - -

i can't say why i chose to take a class in contemporary Chinese film my first quarter at college, but i did, and my decision to do so is something i have returned to often since. it's not that i took the class itself particularly seriously, but i found the content to be highly compelling. i would go on to largely ignore China for he rest of my college career, but i always took an interest when anyone i met had been there or spoke Mandarin. my enthusiasm for the history of the group of civilizations comprising what we know of as China is largely unconstrained, a fact that i have made real (and somewhat pitiful) efforts to encourage in myself and those around me. when my sister spent a year in Beijing, i downloaded some Mandarin instruction tapes and made lame attempts to get through the first couple of lessons. when i worked with a Tibetan carpenter (and friend) for the better part of year, i pestered him to tell me about his life and travels, and encouraged him to bring in some Tibetan music. and to his credit, he did - and to the discredit of the shingling contractor i had hired, an awkward period ensued.

it's tough being a bike mechanic. wages are generally low. the work is dirty and requires both technical knowledge and (unlike many auto mechanic jobs) a significant amount of customer service. moreover (unlike most construction jobs), information turns over rapidly, and mechanics are expected to keep up with new technologies as they develop.

as a part time employee whose specific intent is to be just passing through while i figure out my career, these factors don't particularly bother me. besides, i've made my peace (after years of frustration and hurt) with the bicycle industry. at this point in my life, it's just a skill i have, and a way to support (part of) my lifestyle. it also serves as a place where i can test my ability to maintain a positive outlook and interact pleasantly with a wide variety of customers - not skills i have spent much time developing in the past few years.

and so, when a job i'm working on offers resistance to my efforts, i react mostly with bemusement. not surprisingly, i have opinions about the quality of the bikes i encounter, and much of the stock product that even the nicest shops (of which my employer is certainly one) carry falls below my personal standards. i find working on these bikes to be a particular pleasure, specifically because i would, generally, consider them unacceptable for my own use. for despite my (arbitrary and capricious) standards, most bikes are simply a pleasure to ride. this fact has been a revelation to me: i will, regularly, find myself genuinely enjoying the test-ride of a bike which, just minutes earlier, i had proclaimed to be "complete crap." to be totally fair, it is the case that i have a history of taking pride in accepting my own wrongness - a phenomenon that an astute critic might point out is equivalent to acting more right about my own mistakes, and hence more right generally, than even my most astute critics. regardless, i revel in my own ability to truly enjoy the bikes that i, from a technical standpoint, like the least.

and all of this, of course, is from the standpoint of the mechanic. from a consumer's perspective, the case is even more stark. crappy product is, often times, far and away the best option. if you disagree, i would be happy to up-sell your $800 Felt for a $10K American-made bike, but i can tell you with all honesty that the incremental return on investment will be infinitesimal.

it is my impression that these facts are highly troubling to most mechanics. anyone scraping by in NYC working for $15 an hour knows that there are a few billion people in the world that would kill for a fraction of that wage, and i think it's not lost on such Americans that their hold on such relatively high wages is precarious. sure, many of these people have delusions of grandeur as likely - or unlikely - as my own (it's not only i that am making a stop as a grease monkey on my way to a career). but i have put in my time defining myself as someone of the bike world, and after i was done, i put in my time defining myself as someone apart from it - and now i'm just a guy who can, if called upon to do so, build, diagnose and fix bikes. it's possible that some of my coworkers feel similarly of themselves, but i have seen no indication of that.

viz. their highly confused attitudes towards Chinese production. keep in mind, these are, from all appearances, totally kind and fair-hearted people. a few of them speak Spanish fluently and are fond of conversing with the delivery guys (who ride, almost without exception, bikes that are dirty, poorly maintained, and generally unpleasant to work on) in their native language. certainly, nobody would think of making derogatory comments about blacks, Native Americans, or homosexuals in the shop. and yet, when the issue of the poor quality of inexpensive stock bicycles come up, they find it acceptable to deride not the Western companies that sell and distribute the product, but its country of origin.

"china sleepy" is the most succinct manifestation of their sentiments. the phrase apparently is meant to reference the laziness, or perhaps exhaustion, of the individual Chinese worker who produced the item in question.

i had not heard the epithet until recently, and it reminded me of one i encountered on jobsites many years ago: afro-engineering. i can't say i'm a fan of either phrase.

it would be one thing if these kinds of slurs were simple racism, but they're not; they are pointed criticisms of the purported inability of a culture (or, more often, group of only marginally related cultures) to produce product of a particular quality. never mind that manufacturers like Foxconn build some of the most technologically advanced devices in the world. disregard similarly that the pyramids at Giza (located wholly in Africa) remain some of the most fantastic engineering feats in history, involving a peak workforce of perhaps 40,000 workers. these sentiments ignore all reason to the contrary: the other is incompetent. end of story.

drill down a little, and you'll find the speaker will shift from the individual worker to the planners of China's economic policy. and sure, the Chinese government pegged the yuan to the dollar for about a decade. but that relationship has, since 2005, changed, and the result (as documented by Edward Lazear in the Wall Street Journal) is interesting:

The dollar-yuan exchange rate did not change from 1995 to 2005, and during this period China's exports to the U.S. increased sixfold, or at a rate of about 19.6% per year. Then, from 2005 to 2008, the value of the yuan relative to the U.S. dollar appreciated by about 21%. China's currency was "stronger" and its exports in dollars were more expensive—so Chinese exports to the U.S. should have fallen. Instead, China's exports to the U.S. continued to grow at about the same pace, averaging 18.2% per year.

The only period during which exports from China to the U.S. fell to any significant extent was during the recent recession, dropping by about one-third from late 2008 to early 2010. The dollar-yuan exchange rate was unchanged throughout this entire period. The obvious explanation for the decline in Chinese exports to the U.S. was the decline in demand for consumption goods in general.

clearly, these are complicated issues; far be it for me to attempt to reach any meaningful conclusion, here or elsewhere. my policy is simple. if you don't understand it, be interested in it - not scared of it.

a few nights ago, i was riding through the East Village and decided to stop into Dumpling Man for a quick dinner. i normally prefer the grittier spots in Chinatown, but Dumpling Man was on my way and i wanted to double-check my initial impressions of it, which was that it was okay (they serve fucking dumplings, after all, and i love dumplings) but not great.

i ordered some seared pork dumplings (texturally interesting but not particularly flavorful) and some xiaolongbao (which were abysmal) and sat on the street. the chef appeared to be Han Chinese, but the manager (or anyway the man at the counter) was white, though he seemed to speak Mandarin fluently. about halfway through my meal, a couple of girls walked up and, after some hesitation, entered the small restaurant. i could hear them discussing options with the manager, who advised them on filling options and order quantity before breaking off the conversation to holler out the window to the chef, who was leaving. they yelled back and forth, laughing at each other - completely in Mandarin - for a minute or two, and the girls stood at the counter in amazement.

i don't know what they really thought, and it would be dishonest for me to speculate. moreover, it's not as if my position - the enlightened westerner, just here to experience all the cute foreign ways of other cultures - isn't problematic.

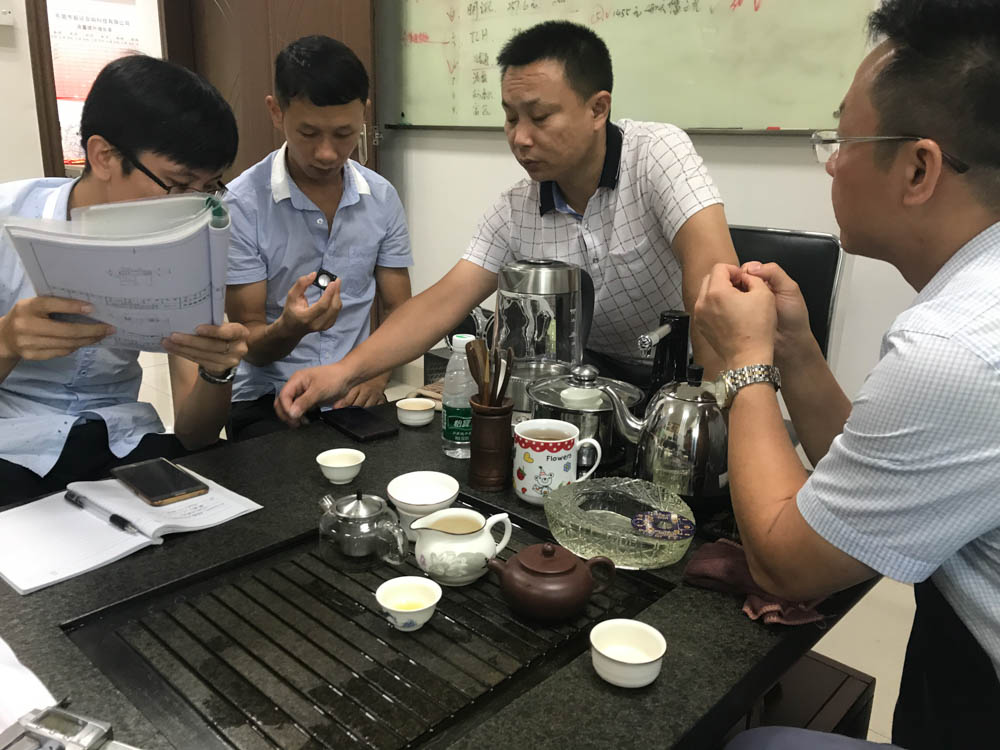

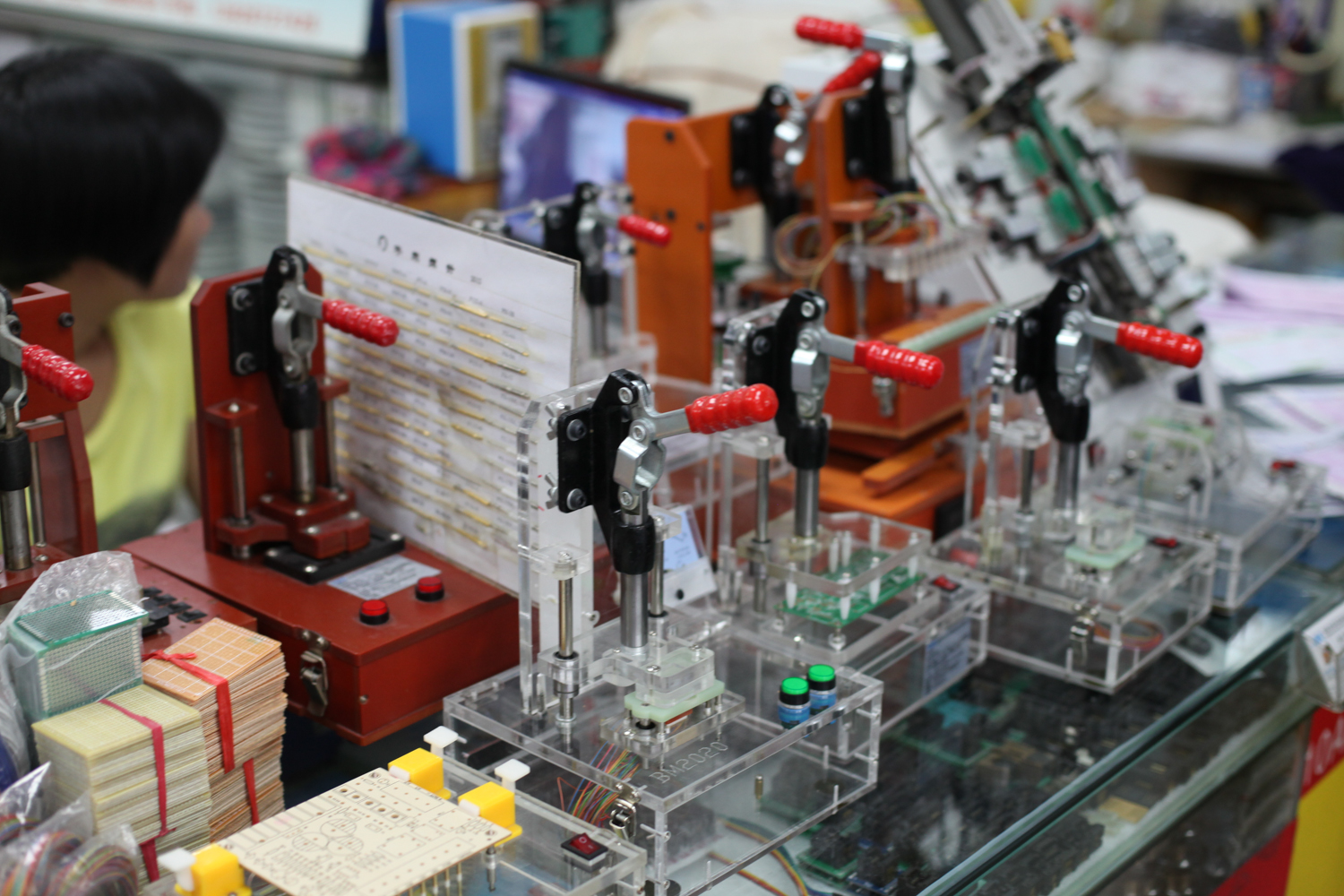

i went to Shanghai in 2011, for an expenses-paid work trip. i had wanted to travel to China for years, and the opportunity to do so - and to visit factories there, no less - was a gift. the trip was organized by mfg.com, a website whose service is essentially linking buyers of manufactured goods with job shops capable of providing those goods. the buyer base is, as i understand it, largely Western, but it seemed to me that mfg.com's real customer base is worldwide suppliers, and that the product that they sell those customers is access to the eyeballs of a Western clientele.

the trip was fairly busy, but i found plenty of downtime - not least because i never acclimated to the time difference during my five-day trip. and so i explored on foot, visiting a variety of what seemed to be normal Shanghainese neighborhoods. i walked down sleepy streets lined with old sycamore trees. i found little food courts and gestured at crisp sesame pancakes and greasy dumplings, and found myself in low-slung slums where public services were totally ad hoc and sheet metal was the primary construction material.

i was a bit astounded that my tripmates didn't act similarly, but try to this day to understand and appreciate their methods of approaching the culture. they were mostly confined to the hotel restaurant - a place i eschewed - and squirmed as we were served eel and turtle at dinner on the town. to be fair, many of these people had worldwide procurement experience that my small-time resume couldn't touch, and many of them were able to capitalize on the opportunities the trip provided in ways that i certainly didn't. nonetheless, i got the feeling that they viewed the country as an other place, where i tried to see it as just another one.

it wasn't until my last day there that the most significant reason for this difference occurred to me. the trip organizers had scheduled a van to take a few of us across the sprawling city to its airport, and i met up with my vanmates in the hotel's parking lot ten or fifteen minutes before our departure time. the hotel was new, modern, and nice. my room cost about $200 per night, but the equivalent in New York would likely have been double that. the neighborhood was clean and had plenty of amenities acceptable to both Western and Chinese visitors. and parked in the small driveway in front of the hotel was a shiny red Ferrari. the car likely had a sticker price in the $200K range, though who knows how much the import to China cost. it was a nice vehicle, but not one that struck me as particularly unique.

i spent my formative years in Southampton, New York - one of the most vibrant resort communities in the US. in the summer, Ferraris were almost ubiquitous, and one learned to recognize cars that were interesting, as opposed to just expensive. but my vanmates - who were by all appearances intelligent, informed, and even worldly people - didn't have such a sense. and so it was i who snapped the photos of a woman from Atlanta, leaning gingerly over the hood of an Italian supercar in a nice neighborhood in Shanghai. who else was going to do it?

the previous night, i had taken a subway, and then a bus, to a decidedly normal neighborhood in Pudong, Shanghai's rapidly developing expansion zone. my companion, a Shanghainese college student who had been hired as a translator for our trip, had somewhat awkwardly agreed/suggested (we were both being a bit coy) that it would be fun to take me to Pudong for my last afternoon in town. we were both exhausted, but i was enjoying my last few hours in the country, and as she went up to her parents' apartment (i wasn't allowed), i must have looked like some weird caricature of a tourist, far from his hotel but seemingly unbothered.

she took me to a greenmarket and helped me buy mangosteens. we walked past open air restaurants, ate noodles from a cart, and went to a supermarket, where i browsed wide-eyed and insisted on buying green tea oreos. and then we returned to her street, where she asked for my business card and i awkwardly (and perhaps inappropriately) hugged her. i was emotional. i liked her, and i deeply appreciated her willingness to befriend me despite the fact that i was, for all intents and purposes, just some Western businessman in China for a few days.

- - -

ultimately, my gripe with "china sleepy" is that i don't understand who it's meant to be a criticism of. the factory workers i encountered in Shanghai, Suzhou and the surrounding area certainly didn't seem sleepy. their bosses - enthusiastic business owners, desperate for Westerners to come in and justify the doubtlessly large investments they had made in their factories - weren't sleepy either. and the companies - Western, Chinese or otherwise - that contracted the factories we saw to make parts? they're getting ahead any way they can, just like the rest of us.

the last thing i want is to condone, wittingly or not, the mistreatment of workers. and i'm no more likely (my enthusiasm for cheapish bikes notwithstanding) to buy inferior product than the next guy; i surround myself with the same collection of silly knick-knacks that one would find on Kaufmann Mercantile and Canoe. but to denigrate the work ethic of more than a billion people, and to categorically label their collective output as "crap," seems to me an injustice of equal magnitude.

and ultimately, it's more productive - and more fun - to like, and to be genuinely interested in, China. a culture doesn't survive four millennia, and multiple fractures and reunifications, without developing at the least a compelling storyline or two. it behooves us to appreciate China for that, and it behooves me to appreciate its people for the kindness and generosity i experienced there - if not for the opportunity to ride an affordable bike around the block (after a little fiddling, of course) on a beautiful afternoon in june.