During Design

As a hardware product designer, I want my suppliers' parts catalogs integrated into my design environment, so that I can seamlessly browse for new parts and view part data directly from my modeling software.

Autodesk Inventor is my go-to design software, and McMaster-Carr is my go-to parts supplier. I'm constantly browsing McM for a part, then adding it to an open order, then downloading the STEP file and importing that into my model. I consider this a luxury: McM's decision to include STEPs for the vast majority of their mechanical parts makes my job a ton easier. But the process is convoluted, and a lot of part data is lost. On parts like socket cap screws, for instance, McM tracks the following data:

- Thread size

- Length

- Thread length

- Material

- Package quantity

- Package price

But their STEP files contain none of that; all that's included is the part number and the material, which is often stripped of a lot of useful data (parts described as "Type 316 Stainless Steel" on McMaster's site often show up as either "Stainless" - or worse, "Generic" - in the STEP file).

For McMaster-Carr to become more fully integrated into my design and procurement process, they should include comprehensive part data in all of their STEP files.

Moreover, there's a larger opportunity for McMaster to integrate their catalog directly into my design environment. If their catalog were available as a plugin for Inventor/Solidworks, designers could browse, design, and purchase all from one seamless interface - which I believe they will demand in the near future. Look at Plethora and Sunstone Circuits (and in web development, Squarespace) - across the hardware world, the movement is towards integrating design & supply chain management. McMaster-Carr is perfectly positioned to become a powerful player in the field.

During Prototyping

As a prototyping mechanic, I want real-time internet enabled inventory management, so that I can understand what parts I have on hand & prepare for shortages before they happen.

Small parts management sucks. With their lightning-quick delivery and vast catalog, McMaster is the cornerstone of most prototyping shops' parts management system. But that solution is awkward at best, and often requires simply ordering more parts, even if we have some (somewhere) on hand.

Small scale inventory management has historically been extremely difficult, but today it's increasingly easy. For instance, Quirky has shown us that it's not that hard to keep track of the number of eggs you have in your fridge, and Tesla's iOS app shows the charge state of your car's battery. It's only a matter of time before the same is the case with things throughout our physical lives, and McMaster-Carr is uniquely positioned to take small parts management on.

I envision a small parts cabinet full of sensors (some combination of force, optical, or proximity), which would periodically update an online database as to the quantity of parts inside each bin. But you needn't even start there. An easy MVP would be an iOS app that allowed the user to snap a photo of a small parts cabinet and tag each bin with a part number & quantity. The photos would be collected and stored online, and would be linked to the customer's McM order history.

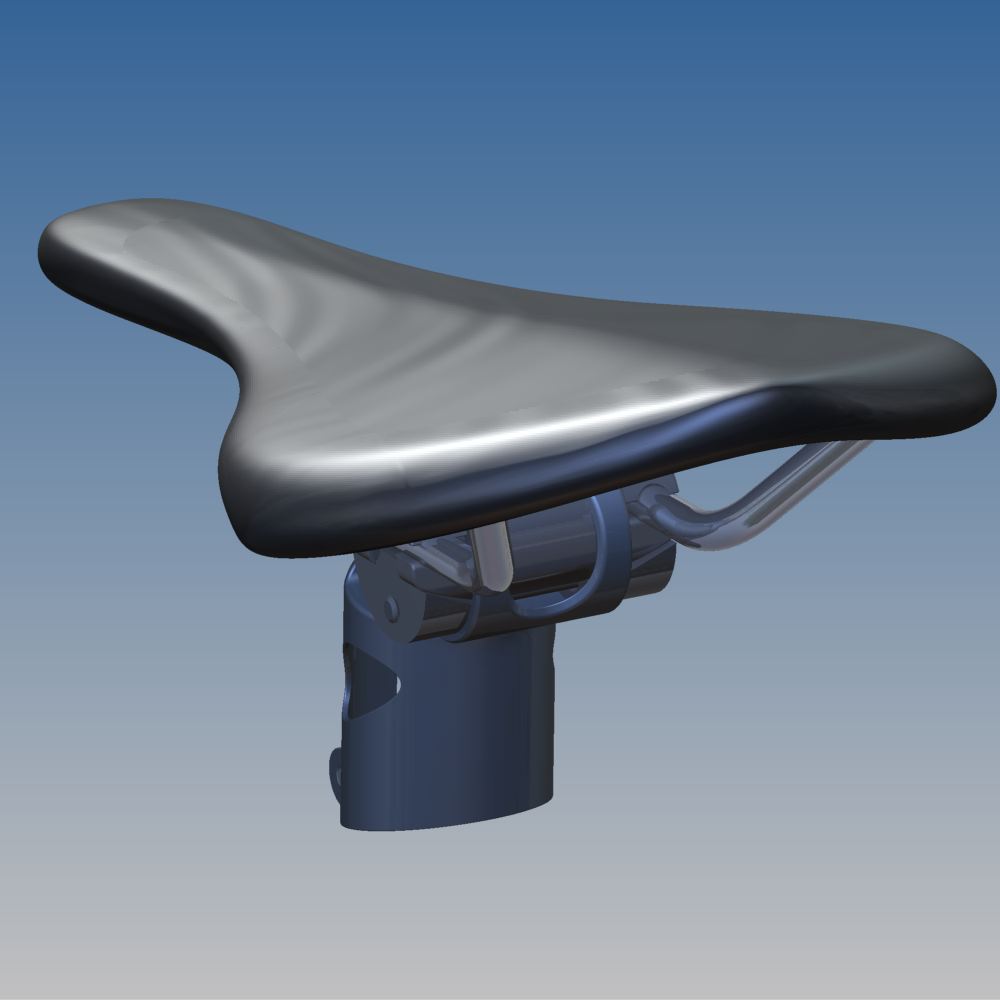

Then, when a mechanic takes a handful of bolts out of a drawer, all he needs to do is update the inventory count from his app. By tapping around a set of linked photos in the app, he's directed to the bin that he's physically looking at - and he can confirm visually that the parts are what they appear to be. By tapping on an "info" tab, he brings up the inventory data (including links to a 3D part file, technical data, order dates, and a list of mating parts/assemblies that the part has been used in - culled from the Inventor plugin described above) and assign a piece count to a job & edit quantity on hand in moments.

McMaster-Carr should build this system - starting with an iOS app that offers basic inventory management. Doing so would give them a view into their customers' usage data, and would help users streamline their restocking process. The days of bins labeled with bits of paper are numbered, and users will soon demand personalized (and internet-enabled) inventory management systems. McMaster is in a unique position in the marketplace, and has the opportunity - if they work now - to strengthen their foothold in small parts management.

For MRO

As a maintenance, repair & operations engineer, I want a single process that incorporates machine data, relevant spare parts, and procurement, so that I can get my facility back online more quickly.

A large part of McMaster-Carr's business is in supporting maintenance, repair & operations (MRO) professionals. These customers have unique needs; their ability to get the right part, right now, can have huge impacts on their company's ability to recover from unplanned downtime due to a broken machine.

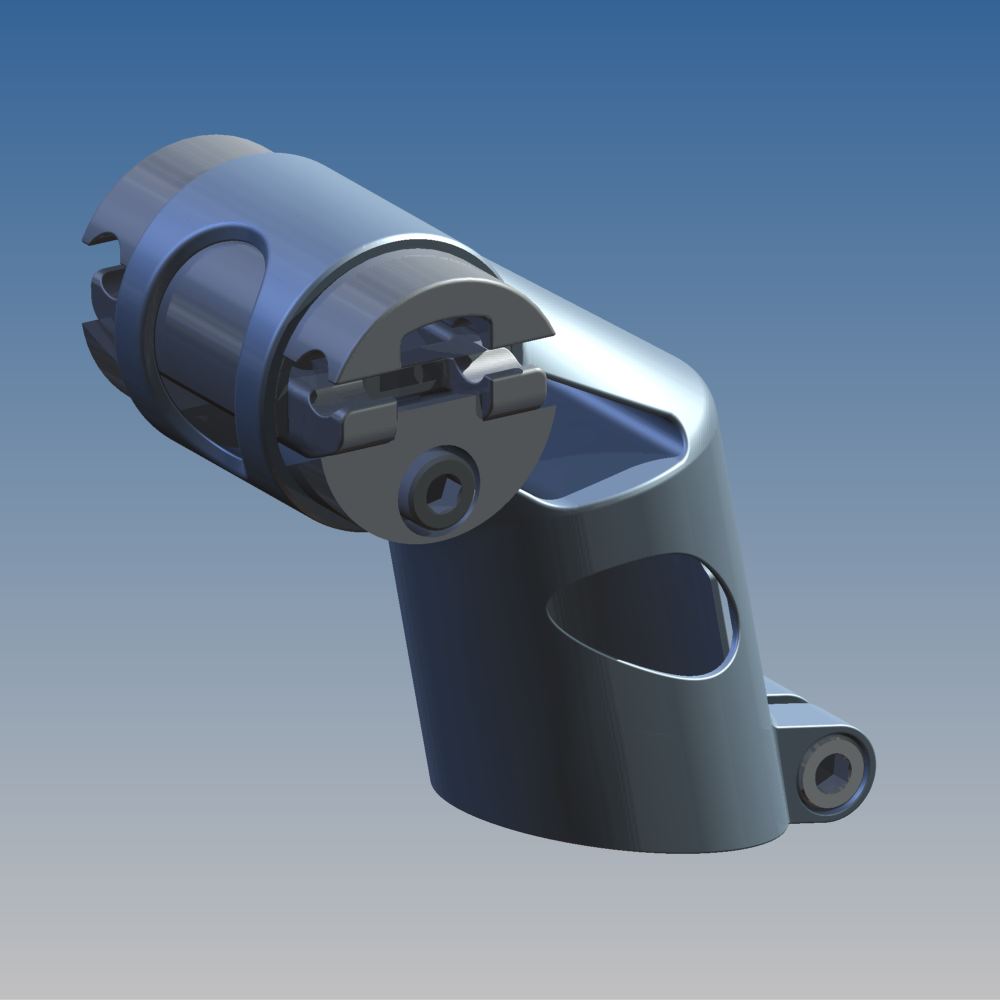

In many cases, MRO engineers will find themselves with a broken part and will need to replace it immediately. Doing so will require careful measurement to determine the part's specifications, a process that can be difficult and imprecise - especially if the broken part has been mangled and/or lost.

McMaster should work to establish a system of folksonomy - user contributed data - that would allow MRO customers to tag parts with information about how and where they can be used. For instance, a particular serpentine belt might be commonly used as a replacement spindle drive belt on an old lathe. Instead of finding this data on the web - and then cross referencing part numbers back to the McMaster-Carr catalog - a tag could be submitted to the relevant part directly in the McM database. Subsequent users could then find the information they need right in the McM website/app.

Such a system would be complicated, for sure. It would require a significant effort on McM's part to hire and train community managers, who would monitor and vet user submitted data on a daily basis. But doing so would allow McMaster to leverage the huge - and growing - network of hardware professionals and enthusiasts. This community is sorely lacking a single go-to reference, and McMaster is in many ways the strongest candidate (with its enormous existing database of part, material & process data) to do so.